Fixing The U.S. Trade Deficit

New U.S. trade deals will likely make slow progress in reducing bilateral trade deficits as the underlying drivers behind the U.S. trade deficit are macro forces. While the U.S. economy outperforms other major trading partners; the value of the USD remains overvalued and as long as tariffs are not high enough to undermine comparative advantage of importing countries, the U.S. will struggle to reduce the size of the trade deficit. This is currently not a capital account financing problem or a restraint on the U.S. economy provided that the U.S. has moderate real bond yields and perceptions of U.S. exceptionalism exist in the equity market.

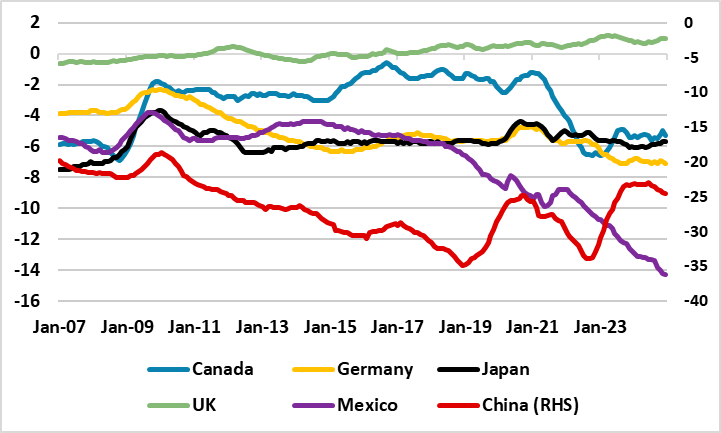

Trump 1.0 trade deals with Mexico/Canada/China and Japan failed to correct bilateral trade deficits (Figure 1). Will Trump 2.0 have any more success?

Figure 1: Bilateral Trade Position with the U.S. (USD Blns 12mth MA)

Source: Datastream/Continuum Economics

China can do a trade deal that directs Chinese companies to make purchases of foreign goods, due to the large size of SOE sector and influence by the Chinese authorities. This is likely to be one of the promises that China makes to the U.S. in trying to reach a phase 2 trade deal (here), which will likely include extra purchases on U.S. agricultural goods given China need for food imports. But how can a more capitalist country make trade promises that President Trump will demand?

Trump discussed the size of the bilateral trade deficit with Mexico President this week, while White House officials also indicated that trade deficits are a concern with Canada and Mexico. Trump will likely be back later in February with threats over the need to revise the USMCA and reduce bilateral trade deficits. The EU is also on Trump radar, where we expect specific threats into the spring on the size of universal tariffs and implementation dates (here).

Capitalist countries can try to boost imports from the U.S. in a number of ways with the aim of reducing the bilateral trade deficit. The 2019 US/Japan trade deal included reduction of elimination of tariffs on agricultural products, as well as transfer of digital data across borders that was favourable to the U.S. tech industry (here). The 2020 USMCA also included digital data provisions for U.S. companies, alongside tighter rules of origin for certain sectors to guard against China building assembly plants in Mexico and exporting goods via Mexico (here).

The technocrats behind Trump will likely want these types of provisions to be wider, while also asking for more favourable tax treatment for U.S. companies or subsides for U.S. goods. The U.S. commerce department will also fight hard to get penalties included in any new trade deals, which will likely face ferocious resistance from other countries. Trump as a negotiating tactic could also ask for payments from individual NATO countries where their payments fall short of his target of 5% of GDP.

While some improvement in U.S. exports could be seen, plus import substitution based on tariffs, the key issues remain relative growth U.S. v trade partners; the value of the USD and comparative advantage.

The U.S. could reduce the overall trade deficit if it grew more slowly versus trade partners, but the Trump/Bessant plan is for 3% trend growth and modest/moderate fiscal stimulation via tax cuts (here). U.S. fiscal policy has been too stimulative since 2020, but will not be corrected without a U.S. Treasury crisis, which is a low to modest risk in the next 24 months if Congress surprises with an aggressively stimulative 10yr budget bill. The other alternative is a buyer strike on overvalued U.S. equities. While a 10% correction is high risk this year, a 25% plus bear market would likely require a U.S. recession, which is also low to modest risk. A major sudden stop in U.S. capital account financing looks unlikely. Overall, it is difficult to see a rapid shift in investment relative to aggregate savings that would quickly reduce the trade deficit.

The 2 issue is the overvalued USD, which is much higher than under Trump 1.0 (Figure 2). G7 leaders will likely tell Trump at the June 15-17 summit in Alberta Canada that the bilateral trade position in part reflects an overvalued USD, with Japan at some stage likely ask for U.S. Treasury help to reduce the undervaluation of the JPY. Trump could even try to jawbone the value of the USD lower. While this could produce a modest decline in the USD, the USD value is largely determined by policy rate; 10yr yield differentials and perceptions towards U.S. assets. Faster ECB/BOE easing than the Fed is a real restraint to substantive USD declines in 2025. U.S. equities and bonds can be volatile, but do not face a 2025 crisis.

Figure 2: USD Real Effective Exchange Rate

Source: Datastream/Continuum Economics

The final structural issue is comparative advantage, where modest tariffs are not enough to derail exports into the U.S. Relative cost of production differentials is one reason behind comparative advantage for certain countries (e.g. China/Vietnam/India, while specialisation/quality is a 2 reason (e.g. Taiwan/Japan/Germany). The solution would be sky high tariffs circa the 60% election campaign threat against China. However, President Trump does not appear to want to go along the maximist trade tariff implementation but rather to use tariffs as a negotiating tool.