Eurozone: Trump Taking Aim at the EU?

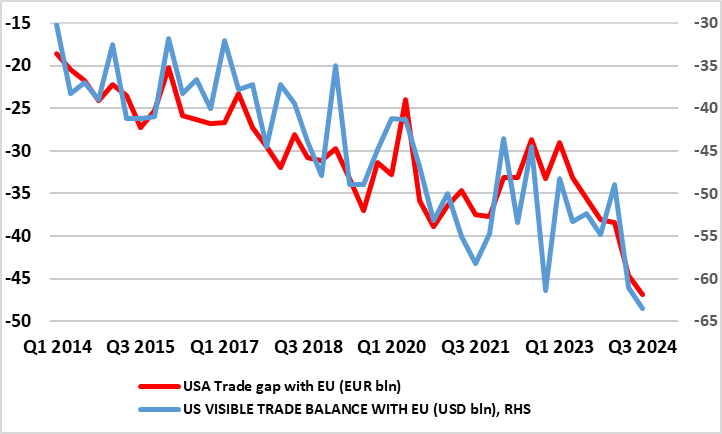

President Trump has made it clear that the EU is going to face US tariffs in the not too distant future. Admittedly, tariff threats have been used as the basis for negotiation elsewhere, this may be the case for the EU too – as was the case during Trump’s first term. As for the EU, it does have a sizeable trade surplus (purely in goods though) with the US, and one that has been getting larger of late (Figure 1). But other issues will determine the size, timing and type of tariffs the EU will likely face, largely though a result of Trump’s political and economic suspicion of the EU. All of which makes any assessment of the economic fall-out to the EU and particularly the EZ very difficult, with the added complication that the EU could face dumping from the likes of China. But we see a potentially significant impact on the EU/EZ not least given the already weak growth backdrop already evident.

Figure 1: A Clear Bilateral Trade Deficit for the US vs the EU

Source; Eurostat, US Dept of Commerce - data is quarterly

Perspective

Trump has described the U.S. trade gap with the EU as being “atrocious”, claiming it to be as large as USD 350 billion (annually). The reality is much different unsurprisingly with Eurostat and US Commerce Dept data suggesting an EU surplus in goods with the US in 2023 (the latest year for which there is available data) of around EUR150 billion, this partly offset by a US surplus in services of just over of EUR100 billion, suggesting a gap in overall trade of around EUR50 billion. This is much smaller than the gaps the US has with other countries; it is a seventh of that the US has with China and less than half of that the US has with Mexico. And while in absolute size it is comparable with Canada’s surplus, this ignores the fact that the EU is almost 10 times larger, so that as a proportion of total GDP (a legitimate comparison), the EU’s trade surplus with the US comes in at a very modest 0.3% of annual GDP, compared to Canada’s 2.5%.

The Hidden Agenda

But (particularly to Trump) size is not everything. In the trade spats Trump is having with Mexico and Canada, there are issues over (illegal) immigration and smuggling while with China there are, longer-term issues (here) albeit with a clear indication of the latter dumping goods abroad. However, as for the EU, Trump has other issues, not least the fact that the EU vies with the US in size both population and economy wise (Figure 2) and is thus an uncomfortable rival.

Figure 2: Size Does Matter: Key Economy Characteristics of Major Economic Areas

Source: ECB – data is largely for 2023

But Trump is also suspicious of the EU as an institution with so many countries working together and for so many years, this accentuated by his thinking that it is not only a socialist super-state but not prone to his form of economic and political populism. More recently, Trump may feel he has the EU more at his mercy given both its current economic weakness and also its clear political fragilities (lack of effective government is several key countries) and clear divides within and between member states. Indeed, Trump may be willing to treat the UK with some delicacy when it comes to tariffs merely to highlight to the EU countries the ‘cost’ of EU membership.

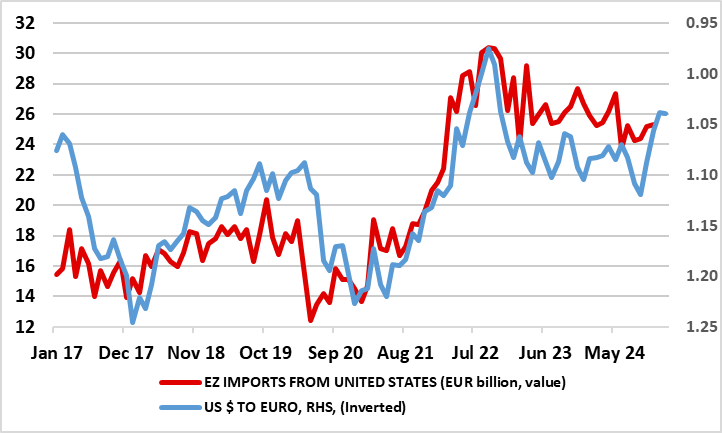

It is also likely to be the case that Trump will be at least partly blaming the EZ for the current weakness in the euro, even though this is more a reflection of relative growth and policy divergences resulting in a strong USD across the board. It is an irony that while tariffs will be aimed at reducing the EZ/EU trade surplus, the strong(er) USD is also likely to reduce the EU surplus (Figure 3) as the value of EZ imports in euro terms is boosted by euro depreciation regardless of the fact that weak EZ growth has curbed import demand in real terms.

What the EU is not prepared for is a blank tariff increase and a supplementary sectoral tariff on EU cars on top. Trump is in a hurry and we see a 10% blank tariff announced February or March for April 1 implementation – in line with the U.S. trade review. The problem is that internal negotiations in the EU and then negotiations with Trump are unlikely to be quick enough and implementation is highly likely April 1. Trump will likely demand a concrete commitment to increase defence spending as a percentage of GDP in individual EU countries, which will not be quick to agree. Additionally, EU cars could be hit by sectoral tariffs in the spring, which could be an additional 10-20% -- Trump hates the scale of EU and German car exports that he repeatedly cites.

Figure 3: Stronger Dollar Boosts Euro Import Bill

Source; Eurostat

The EU Response

In regard to trade and tariff threats, and given his repeated boast that he is fundamentally a dealmaker, it is likely that the EU riposte to President Trump’s tariff will be not to retaliate immediately, but to negotiate as was the case in Trump’s first term. This has already been attempted by trying to placate Trump by offering to buy more US goods (and services); the EU has already suggested buying more US energy, military and agricultural goods as a concession, even though the latter may be somewhat contentious. But a response is likely, with some suggestion that the EU m ay target US tech services as well as aspects of goods exports.

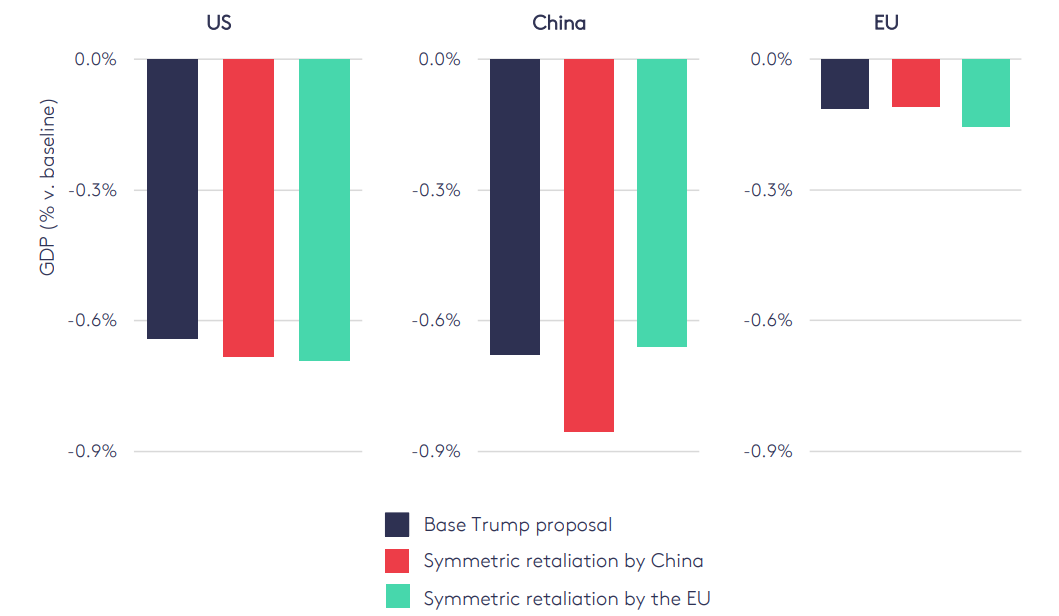

As for the impact, this is obviously hard to judge given the lack of details and timetable. But work has been done to model some likely effects such as that recently by the London School of Economics. This very clear concludes that a likely 10% blanket tariffs from the U.S. on all countries would hit GDP in the United States by -0.64% and in China by -0.68%, while the European Union would face a more modest reduction of -0.11%. Within the impacts would vary significantly: Germany could see a -0.23% drop in GDP, while in Italy the decrease could be negligible and hardly much worse for France. Certain European sectors, particularly Germany’s automobile exports, would be disproportionately affected and may require targeted protective measures.

Figure 4: Macroeconomic Impacts of Retaliatory Measures on the US, China and the EU

Source: London School of Economics

But importantly, the research suggests that retaliatory measures by China and/or the EU would likely worsen economic outcomes for all parties involved (Figure 4) in a damaging trade war. In terms of our forecast the impact could be much more sizeable, depending on how confidence is hit with it unclear as much as to when the main hit would be for 2025 or 2026 – Trump seems to be in a hurry to hit the EU soon as noted above. At this juncture we consider the downside from actual tariffs as a likely reality, but (as suggested above) cannot ignore the likely sustained impact of uncertainty weighing on activity into 2026. Furthermore, while retaliatory measures might seem like a natural response, while they may be counterproductive as suggested above, their threat add to uncertainties.