Tariffs: Inflation may be the biggest worry for the U.S.

While surprising the market in their intensity, Trump’s “reciprocal” tariffs were in line with previous threats on most countries, and with Canada and Mexico being treated less harshly that feared, the net surprise is modest to us. However we do feel that inflationary risks have increased further, which questions bets on Fed easing. This, and a general impression of unprofessionalism on such a key policy event, justifies equity weakness.

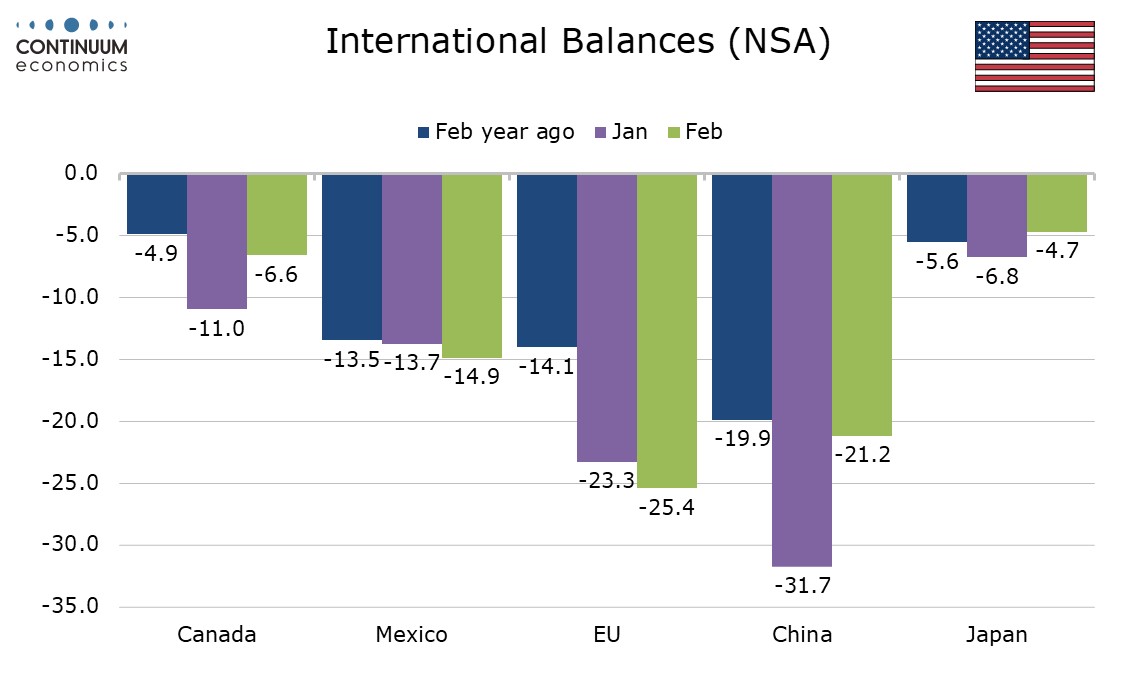

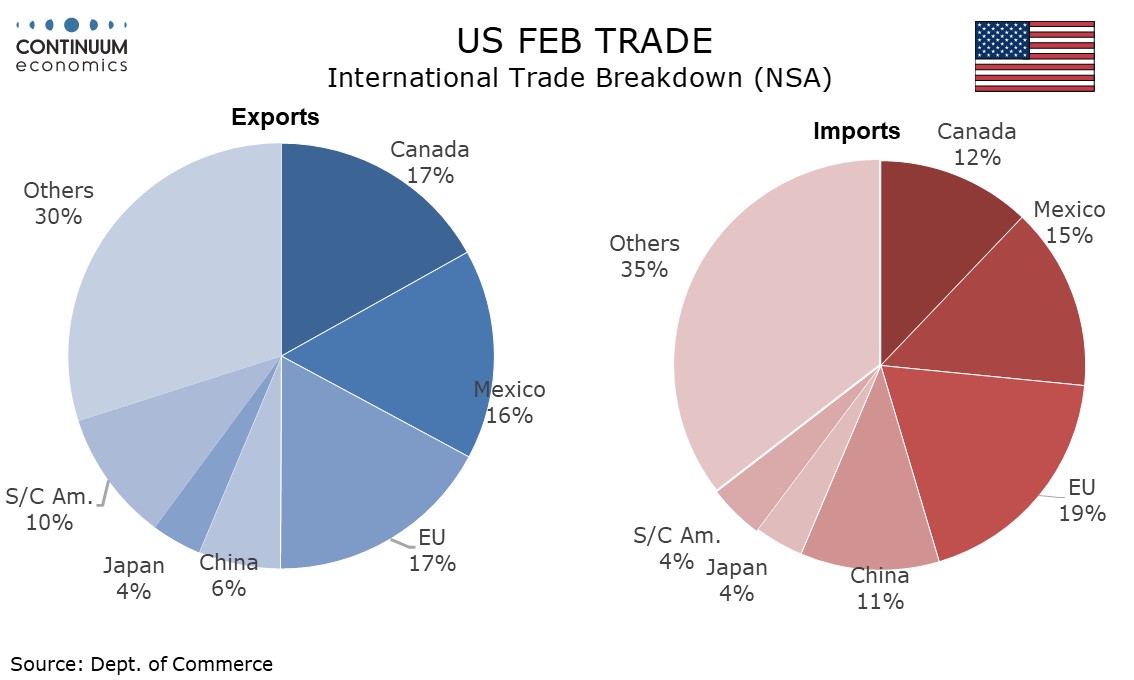

Canada and Mexico were hit with 25% tariffs in early March but soon got an exemption for USMCA compliant goods, and that still stands. While tariffs on autos, steel and aluminum, plus those on non-USMCA compliant goods mean Canada and Mexico still face substantial tariffs, they will now face average tariffs below a global average which appears to be above 20%. This is a contrast to the early days of Trump’s term, when Canada and Mexico seemed to be at the top of his hit list, alongside China.

There was no relief for China, with an additional 34% of tariffs imposed, taking the total to an extreme 54%. A 20% tariff on the EU should not come as too much of a surprise given the tone of Trump’s rhetoric, and that the EU gets treated more harshly than the UK, which sees a 10% tariff, is also no surprise. The main offset to the positive surprises regarding Canada and Mexico came in Asia, with tariffs on Japan at 24%, South Korea at 25%, Taiwan at 32% and Vietnam a massive 46%.

Goods imports make up around 12.5% of GDP, so a full pass through of 20% tariffs could add 2.5% to inflation. While the lift may not be as much as that, it could now be significantly above 1%, and we could see some alarming inflation reports in Q2. Auto prices look sure to rise significantly with prices of imported competition and supplies set to rise, and while domestic production could be stimulated, it will take time. Heavy tariffs on Asian counties, notably Vietnam, which has gained business from China, will mean higher prices of items such as t-shirts and toys. The US is ill-equipped to step up production here, industries which are very different from the high-wage traditional sectors such as autos and steel which Trump portrays as the likely main beneficiaries from his tariffs.

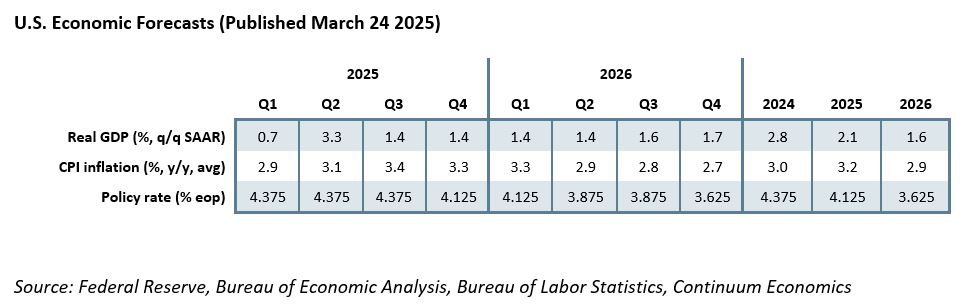

We are more inclined to revise up our inflation forecasts than to revise down our growth forecasts, though we do except GDP growth to slow below potential as a consequence of the tariffs. If the economy is not in recession, and inflation, already above target, bounces by over 1%, the Fed is not going to be in a hurry to ease. While Trump was speaking, Fed Governor Adriana Kugler stated that rates should be held as long as upside inflation risks continued, and was blunter than many about the source of those risks, citing government policy changes, if not explicitly tariffs.

A less than dovish Fed response to a slowing economy justifies equity weakness, though is not a satisfactory explanation at present. Uncertainty is high, with countries considering retaliation but for the most part looking set to do so carefully. That Trump has eased off somewhat on Canada and Mexico suggests the same could happen elsewhere if the risks to the US become clear. Still, that only adds to the impression of unprofessionalism. The tariffs Trump claims the US is receiving by country, to which he has responded with a 50% match, have been exposed as a simple division of the bilateral deficits by imports, leading to some particularly odd tariff calculations for some small island nations.