DM Fiscal Consolidation Problems: Politics/Central bank QT and Low Nominal GDP

Some governments are politically reluctant to restrain government expenditure growth or in the U.S. case raise taxes. This means that intermittent fiscal stress and concerns can be seen in the coming years. However, to get to crisis levels would require a government that abandons any attempts at fiscal consolidation.

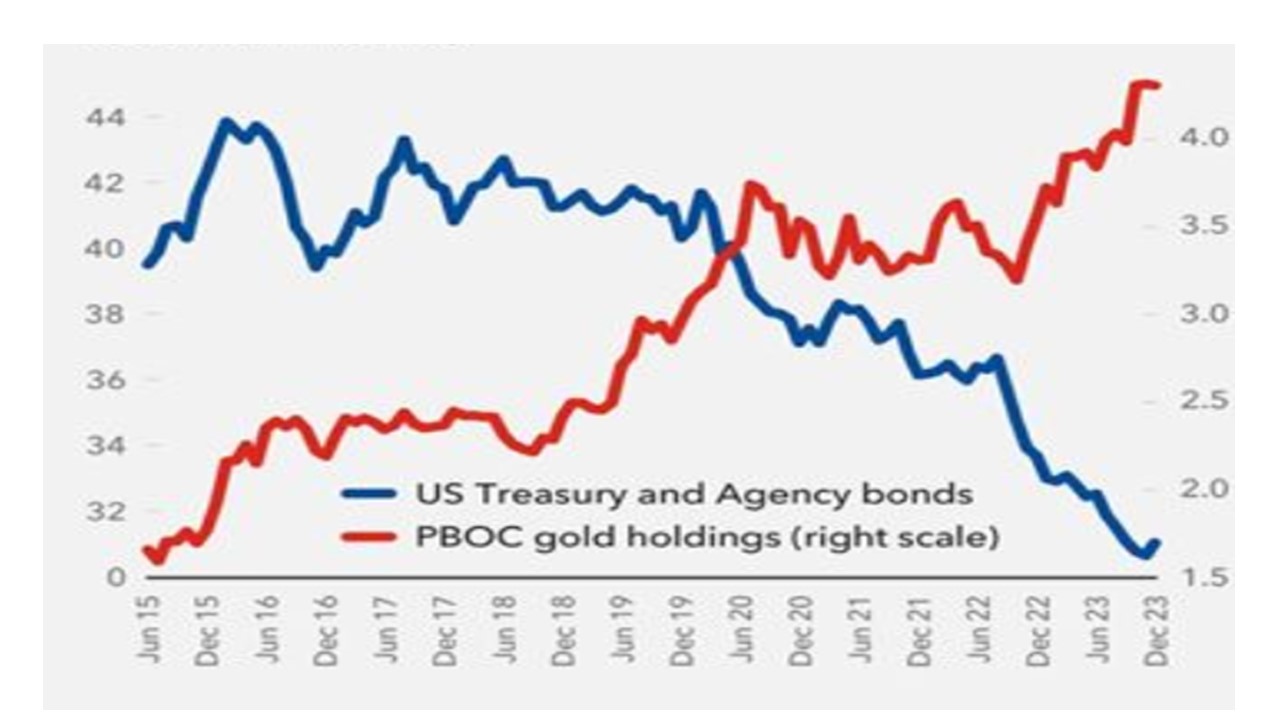

Figure 1: Government Debt to GDP excluding Financial Assets (%)

Source: IMF April 2024 fiscal report

DM government debt/GDP ratios are at a higher levels (Figure 1) than before the hit from the pandemic and the Ukraine related energy crisis (and in Europe energy subsides). Fiscal consolidation is a desire, but current projects suggests the U.S., France and Italy will struggle for three reasons.

· Lack of political commitment. The U.S. government debt/GDP trajectory later this decade at one level reflects the Biden administration deficit financing for renewables and other commitments. However, at a deeper level U.S. voters do not want to pay more taxes and are reluctant to see key expenditure growth restrained (e.g. Medicare). The U.S. election outcome in November will not change this picture and we see fiscal stress in H1 2025 due to politics (here). In France and Italy, voters are reluctant to see a reduction in expenditure growth to help fiscal consolidation and this restrains the ability of governments to undertake fiscal consolidation. In France, spending as a percentage of GDP (at over 57% of GDP), is the highest in the EU and the country has not reported a primary budget surplus since 2001.

· Central bank QT. QT puts extra funding pressure on the private sector, which can demand extra yield and mean higher interest burdens for government. The good news on the U.S. is that the Fed have already cut the monthly cap to $25bln of Treasuries per month. Meanwhile, though the BOJ is trying to move towards normalization, it remains unlikely in the next 12 months that a formal QT program will be announced – though small intermittent shrinkages of the JGB holdings could be seen, as maturities outweigh lower gross monthly buying from the BOJ. France and Italy have a tricky backdrop, as the ECB appear committed to carrying on QT during the ECB easing cycle. This will likely scale up to EUR45bln for the APP and PEPP by H1 2025 across the EZ. While we would argue this is monetary tightening (here), the ECB consensus appears to want to get the huge balance sheet to a more manageable size over the remainder of the 2020’s.

· Low Nominal GDP growth. The 2022 benefit from high inflation to reduce government debt/GDP ratios has passed, as nominal GDP comes down towards the combination of trend growth and the inflation target. In the U.S. nominal GDP should still be around 4% in coming years, but in France/Italy and Japan is 2.5% or below. If nominal GDP grow is slower than average interest servciing costs, then government debt/GDP builds up.

Could these long-term fundamentals become a government debt crisis? Yes if the politics prompt a shift to a government that is opposed to fiscal consolidation and wants to expand fiscal policy stimulus. This could happen in certain circumstances in the U.S. (e.g. if Donald Trump is elected and wants to go well beyond making his 2017 tax cuts permanent), but we feel this is unlikely in 2025 and thus we see U.S. fiscal stress rather than a fiscal crisis in H1 2025.

For France and Italy, it would require a government that rejects EU long-term fiscal consolidation. This remains unlikely in 2024/25, with France unlikely to see such a shift in the June/July parliamentary elections (here) and Italy PM Meloni not feeling political pressure from her modest fiscal consolidation path. Even so, France and Japan have had large debt build-ups since 2007 (here) and this may not be repeated, which is an economic headwinds long-term.

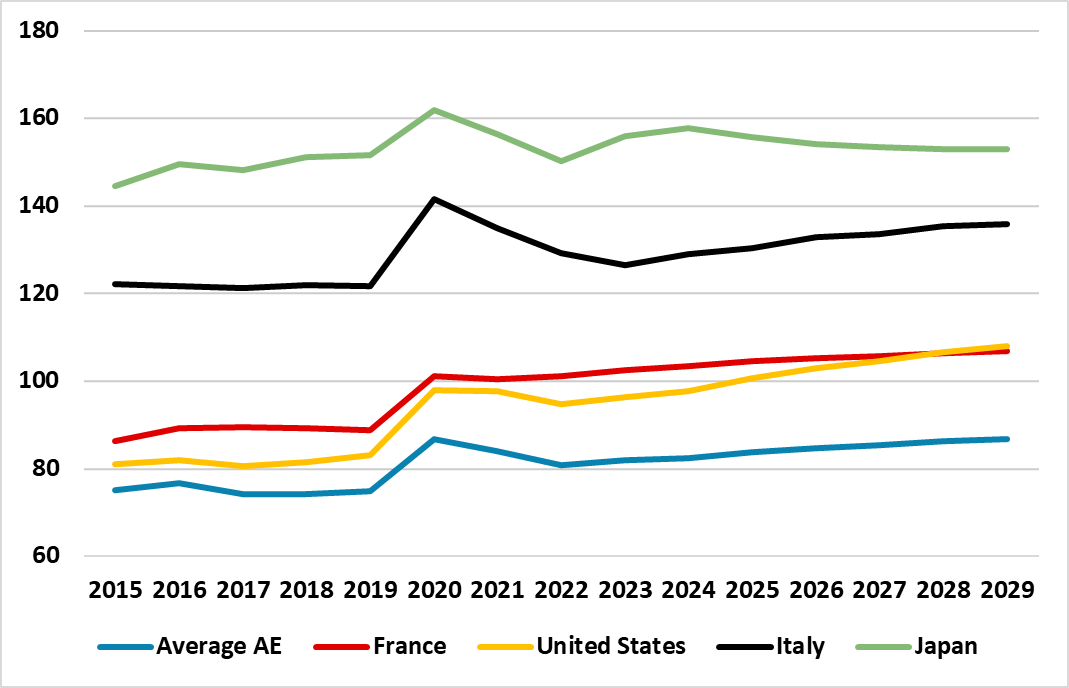

Alternatively, geopolitics could cause problems for higher government debt/GDP trajectory. A China invasion of Taiwan could be preceded by an acceleration of China’s diversification out of U.S. government bonds (Figure 2). However, China’s navy is unlikely to be ready for an invasion until the 2030’s, while Taiwan politics has become less anti-China with the election of a pro-China speaker in parliament. We feel an invasion of Taiwan in the next 5 years remains a low probability. Separately, though China government debt/GDP worries us in terms of crowding out the private sector (here), we do not see a China government debt crisis in markets given the scale of creditors and borrowers heavily influenced by China authorities.

Figure 2: China USD Bond Holdings and Gold (% of FX Reserves)

Source: IMF (here)

While fiscal crisis are not a central scenario in any of these countries in the next 1-2 years, we would feel that the long-term fiscal pressures can be a key talk point intermittently in markets. In Italy’s case 10yr spreads versus Bunds should be 160-180bps. With economic recovery in the EZ, we see the 10yr spread at 160bps end 2024 and 160-80bps end 2025, this also means outright rises in 10yr Italian yields.