Europe: Economic Consequences of Likely Defence Build-Up

As Europe is forced to consider a massive and rapid ramp up to its relatively mediocre defence spending (Figure 1) as it contemplates a reduction in military support from the US, key questions emerge as the economic effect(s). Will it boost or inhibit growth, add to inflation, and how will/should it be financed. In this regard, research over the years provides no clear consensus evident as much depends on how potential growth fares amid what may happen to the capital stock, working population and productivity. As for any relationship between productivity and defence spending, the various studies point to both potential positive and negative impacts. But there are short and long term effects. Moreover, Europe at this juncture faces the added consideration that both with relatively modest defence industry (outside of the UK, Germany and France), it also will need to import much of the added defence spending as a means of mitigating likely tariffs as Trump targets trade imbalances. But it does seem as if Europe will need to boost public borrowing at least in the short-term.

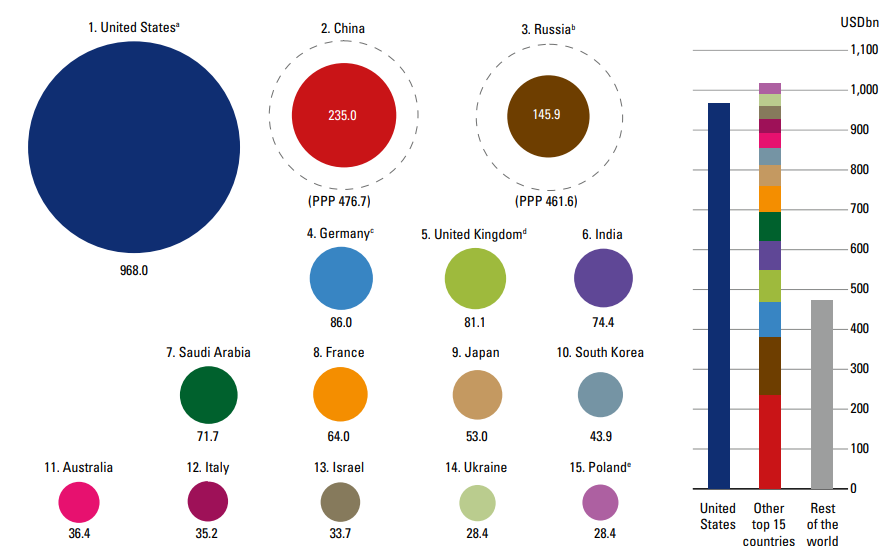

Figure 1: Global Defence Spending Dominated by U.S.

Source: International Institute for Strategic Studies

Pluses and Minuses

On the positive side, the bulk of research does suggest that defence-induced R&D can advance technological progress, while building up military infrastructure can bolster civilian infrastructure, improving overall efficiency. It is also possible that defence spending can lead to more skilled workforce. Less positively, however, there is the issue of crowding-out as added defence spending possibly deflects resources away from other sectors like education and healthcare, also reducing the availability of capital for private sector investment, potentially reducing productivity. Regardless, research does emphasize that the type of defence spending (R&D vs procurement) as well as any economy’s situation and the level of existing technological development.

Spending is Rising

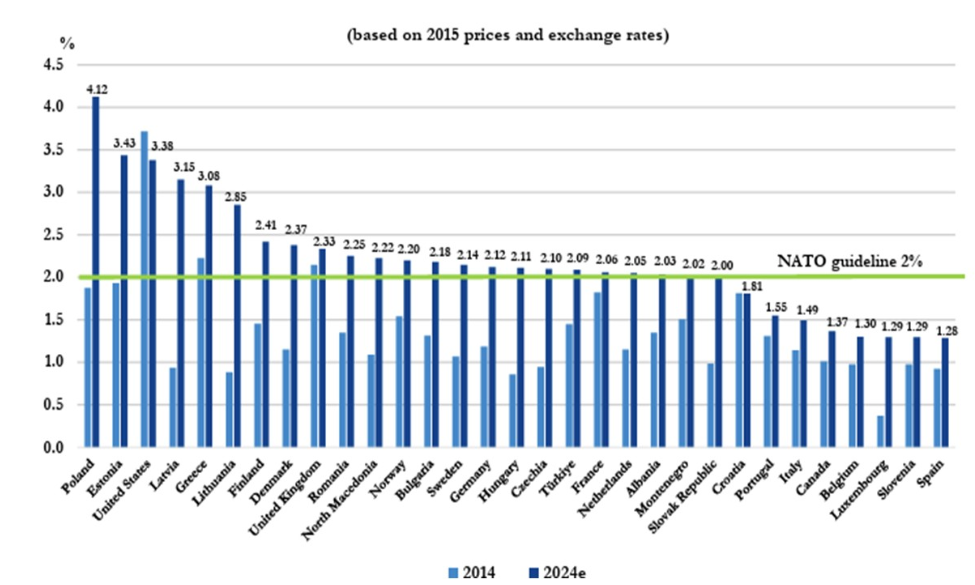

Regardless, higher defence spending is occurring in Europe after Russia attacked the Ukraine in 2022 (Figure 2). Many European countries have increased such spending, albeit with the EU average falling just short of NATO's target of 2% of GDP in 2024 and still well below the U.S., China and of course Russia (Figure 1). But more defence spending looks to be on the cards multi-year as Europe is forced to contemplate reducing dependence of U.S. support whether it be military/defence and/or technological. Indeed, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte has noted that Europe spent well over 3% during the Cold War—and US President Donald Trump has even proposed a new target of 5%. Some clarity could occur by the NATO summit June 24-25 and as European politicians adjust to the new reality (here).

Figure 2: Military Spending on the Rise – Everywhere!

Source: NATO

Some Positives to Focus On

A recent study from the Kiel Institute, however, does suggest that increased defence spending could significantly boost Europe’s economic growth and industrial base if outlays are targeted at high-tech and regionally made armaments. It alleges that European GDP could increase by 0.9 ppt per year if governments raised annual defence spending from the NATO target of 2% to 3.5 % of GDP and shifted from buying weapons designed and mainly made in the USA to home-grown innovations. The added spending of 1.5% of GDP, would currently cost around EUR 300 billion per year—but the study suggests this sum could also generate a similar amount of additional economic activity, if properly spent on developing European capabilities. It thus argues against the widely assumed” guns or butter” trade-off: more money, labor, and raw materials channelled to military uses have not traditionally come entirely at the expense of private consumption.

Outlook Complicated and Uncertain – Of Course!

However, and as suggested above, the net impact on the economy will depend on a number of factors. In particular, it implies that GDP growth will be possibly negative, if increases in defence spending are financed from the outset by higher taxes – added borrowing should occur in the short-term. But of course fiscal positions vary greatly across Europe something that will complicate how, who as well as when the military purses are opened up more. Most importantly, the report emphasizes European governments should ensure that more defence spending ultimately stays within the region, this all the more notable as some 80% of defence procurement currently comes from suppliers outside the European Union. But it does seem sensible to conclude that a focus on domestic production is needed to generate the so-called technological spill overs to other industries and productivity gains that make defence spending generate significant economic activity with each euro spent. Thus this would require a reorientation more towards European R&D - seemingly, the US spends 16% of its military expenditure on R&D, ten times more in absolute terms than the EU's 4.5%. As the Kiel Report notes, there is evidence that R&D spill-overs into the private sector mean that an increase in military spending of 1% of GDP raises long-term productivity by a quarter of a percent.

Politics Enters the Fray

The other issue is that an overall EU army remains too politically difficult and the build-up of military spending in the EU would be at a national level and hopefully coordinated at a NATO or EU level to ensure common procurement and equipment. Additionally, the willingness to commit defence forces for European rather than domestic aims is also in question, with Monday’s Paris summit seeing Germany, Italy, Spain and Poland reluctant to consider peace keeping troops in Ukraine and the UK changing position to include a U.S. backstop – which is uncertain after last week’s events.

Overall, the broad thrust of research suggests that, in the short run, military spending typically stimulates economic growth. But there is nothing typical about the current juncture as Europe faces not only a U.S. keen to reduce its European defence spending but where Europe may have to import much of any increase in military budgets both to address the trade imbalance so clearly troubling President Trump and given the small size of the European defence industry. Against this backdrop, consideration regarding evidence as to whether military expenditures crowds out private sector activity, are of secondary importance as is any consensus as to whether the economy is generally resilient to such shocks.

However, this is still a time for discussion as to how any defence build-up should proceed after the short-term. Achieving optimal outcomes requires a carefully calibrated approach to funding, with temporary expenditures ideally financed through debt and permanent commitments possibly requiring fiscal adjustments to ensure sustainability. While common borrowing for defence is one option, CDU leader Merz has been opposed to this idea. Discussions in Paris thus appeared focused on EU flexible-deficit rules, but different government have divergent government debt/GDP trajectories. Turning to the long-run effect, military-driven investments in R&D and large-scale procurement have historically catalysed significant technological advancements and allowed for productivity gains through economies of scale and learning-by-doing. There is evidence of positive spill overs to the civilian sector. Yet, the strategic focus of these investments poses risks of misallocation or entrenchment.