Western Europe Outlook: Price Pressures - Puzzling or Possibly Persistent!

· In the UK, we continue to retain our below-consensus GDP picture for this year, with growth actually downgraded and with downside risks that may actually be both increasing and materializing. The BoE will likely ease further through 2025 by at least 75 bp and maybe faster and into 2026 too.

· As for Sweden, despite what has been a clear easing in both monetary and fiscal policy stances, the growth outlook still seems weak and where the Riksbank’s activity optimism is overdone, probably meaning a little further policy easing from the latter can be expected.

· In Switzerland, GDP numbers have appeared more than solid, but rather than being indicative of above trend growth, the economy is actually showing a below-par performance, but not markedly so. Even so, the SNB is most likely done, easing wise!

· In Norway, after a mediocre 0.6% GDP outcome last year, the picture for 2025 is only a little better at a downgraded 0.8%, this below-consensus figure encompassing the continued pinch of (yet to be eased) monetary tightening alongside weak growth elsewhere.

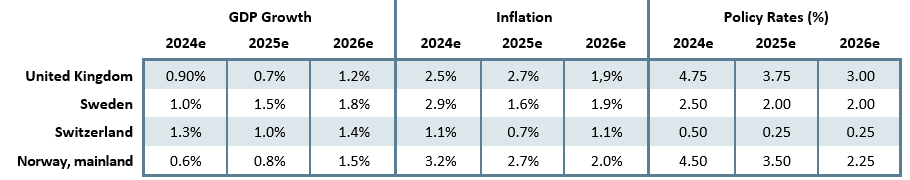

Forecast changes: Compared to our December Outlook, GDP growth forecasts have in been downgraded for the UK and Norway, this not unrelated to the slowness their respective central banks have been to ease, this also forcing a revised policy outlook for both. For both, there is also a clearly higher inflation envisaged this year, but where these we still suggest a durable return to (or below) for all central bank inflation targets into next year. Our policy and economic outlook is little changed for both Sweden and Switzerland!

Our Forecasts

Source: Continuum Economics

Risks to Our Views

Divergent Policy Paths?

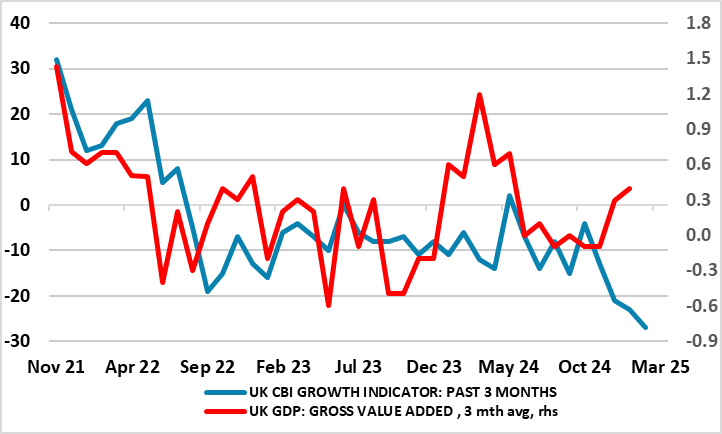

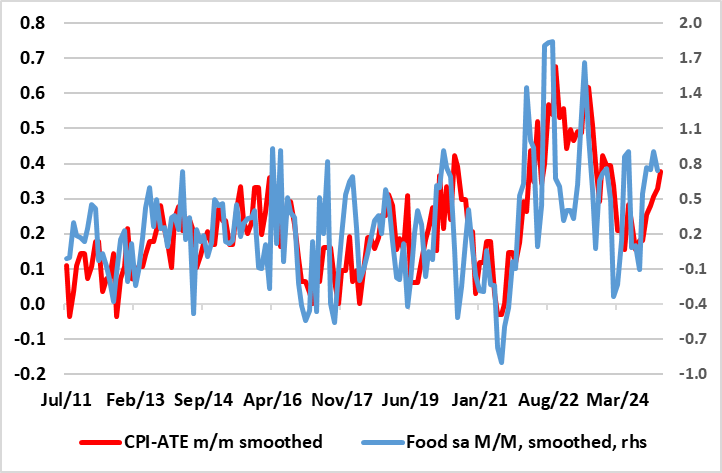

Compared to what we envisaged three months ago, the W Europe 2025 growth picture is more divergent, but still below par. But there are still similarities in some aspects. Firstly, a broad recovery in residential house prices that has seen gains in excess of 3-4% y/y. This is all the more notable given a clear and seemingly increasing divergence regarding the start and speed of monetary easing. Sweden and Switzerland have presided over fairly rapid easing cycles, with probably a little further to go in Sweden and where the SNB may now enter a prolonged pause. However, policy reticence in the UK, and particularly Norway, may appear to seem more justified given that recent months have seen price pressures pick-up by much than we and all four central banks expected – and this second similarity is on an underlying basis too, although much is related to puzzling jumps in food costs.

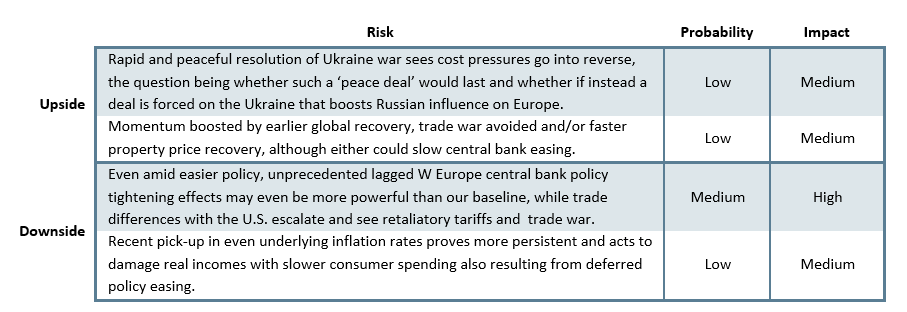

Indeed, there is semblance of a pick-up even in still very low inflation-bound Switzerland (Figure 1). Notably, no such pick-up is evident in the EZ! But a further factor in W Europe has been the impact of the usual re-weighting of CPI baskets that national statistical offices carry out usually at the beginning of each year. Less so in Switzerland, this has resulted in a clear shift to a higher weighting for services in the respective CPI baskets, all the more important as services inflation has been running higher than the rest of the basket. It can be argued that this is merited but the re-weighting has been unexpectedly large. But while this has pulled some 2025 average inflation projections higher, this factor is also creating a favorable base effect for early 2026, pointing to a clear possibility that CPI rates will then fall back discernibly.

Figure 1: Price Pressures Rising Across the Board?

Source: CE, seasonally adjusted m/m rate, 3 mth average

UK: Fiscal Reversal Underway?

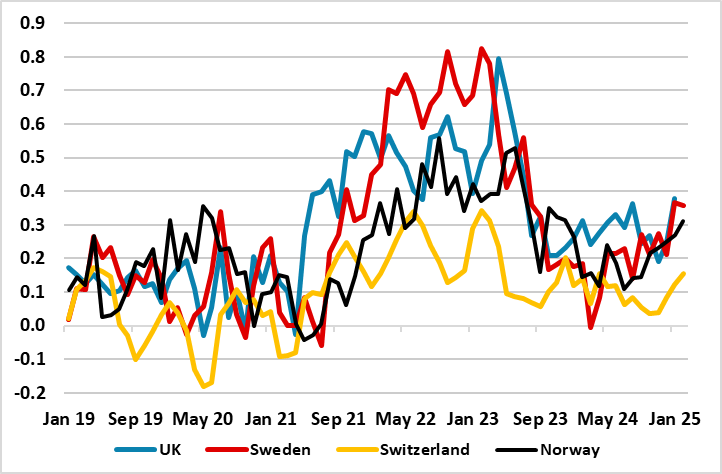

Regarding our UK outlook, we retain our below consensus GDP picture for this year, actually having downgraded the expected growth by 0.3 ppt to 0.7%. This is in spite of November’s Budget delivering one of the largest fiscal loosenings in recent decades worth some 1% of GDP, this actually visible in expected q/q growth rates picking up through year so that cumulative growth by year-end would be nearer 1%. But there are downside risks given the growing evidence that the tax rises and added borrowing financing this extra government spending has caused damage to economic sentiment. Indeed, the looming national insurance rise is already reverberating in terms of business and consumer confidence with the likelihood that the fiscal update due later this month will see more spending cuts to add to the welfare bill reduction already flagged; a sizeable fiscal reversal may be needed to provide a credible repair to ensure the fiscal rules are to be met as well as what may be a very strict Spending Review in a few months. Admittedly, defense spending is being raised but in budget neutral capacity as overseas aid has been cut to finance the initiative. All of which is evident in recent data suggesting some damage to the economy even given what has been clear m/m volatility in official real activity numbers. But this damage is very evident in recent survey data, where a clear conflict is emerging between the two sources of data (Figure 2).

The softer survey data also chimes with increasing weakness regarding private sector employment and government borrowing exceeding forecasts. It also reflects an emerging and worrying loss of momentum in services, alongside more long-standing manufacturing weakness. Most notable is that lagged monetary policy effects may be biting harder than at least the BoE has factored in - the sizeable tightening has caused tighter financial conditions not only in terms of higher debt servicing but also increasingly in record high rent inflation. Indeed, policy is still biting the economy through the credit channel, where real credit growth is still negative. All of which to us means that this year consumer spending may undershoot the 0.9% growth set last year.

Meanwhile, an added headwind is provided by a weaker overall European growth backdrop, most notably for the EZ although this may be more short-lived that previously envisaged given the fiscal and defense initiative the EU is trying to put together. Regardless, a good portion of any fiscal boost may end up boosting imports, which together with the fragile export picture, points to a wider current account deficit than that seen in 2024 (ie around 2.75% of GDP) into 2026. Furthermore, momentum of late has been partly dependent upon non-cyclical parts of the economy, in particular public services, which as suggested above are likely to come under pressure from spending restraint certainly into 2026, if not earlier. This all helps explain our 2026 GDP projection of no more than trend growth of 1.2%, this having been revised down a notch. In support of her high-profile pro-growth agenda, the Chancellor will hope that her non-Budget measures – the so-called seven pillars in the government long-term growth strategy – and a more pro-EU relationship will provide support but, if so, they will have to overcome what has been a dent to the government’s stability aspirations.

There is also the downside posed by (rising) global trade policy uncertainty, possibly best seen in the range of tariff announcements from the U.S, to which some governments have already responded. It is questionable whether a good political relationship with the White House and what is very much a balance bilateral trade with the U.S. will allow the avoidance of the UK facing direct tariffs. But even so, the UK will not escape the global fall-out.

This below-par growth outlook into and through 2025, should add to the disinflation signs seen of late which we suggest hitherto have been a more a result of an easing in supply pressures. Indeed, excess supply is likely to open up into next year and may be even be as much as 1% of GDP in 2026. Thus, it is no surprise that CPI headline had fallen back to target but his has proved short-lived. Instead, a raft of one-off factors has pushed inflation higher so far this year. More notably, while overall inflation may drop back in the rest of the current quarter we acknowledge that the headline will spike back higher in Q2 as a series of regulated prices (water bills) and energy costs take effect. Indeed, inflation may now average around 3% in Q3, some one ppt higher than previously thought but still well below the 3.7% rate that the BoE now project. Regardless, we now see average 2.7% inflation this year (0.7 ppt revised up) but with a little changed 1.9% projection for 2026.).

Figure 2: Surveys Pointing South!

Source, ONS, CBI

As for the BoE, it has altered its rhetoric somewhat to stress the need for policy to be framed carefully as well as gradually. Indeed, this shift very much pointed to what did turn out to be stable policy (Bank Rate still at 4.5%) at this month’s meeting, with it increasingly likely that the MPC majority has no pre-set path considered – at least openly. The BoE still believes that policy needs to remain restrictive, with the appropriate degree of restrictiveness to be decided at each meeting. Given what we think is a flailing real economy backdrop, which growing global trade tensions may only accentuate, BoE easing may yet come around one 25 bp cut per quarter as the BoE reassess its optimism about growth and upgrades its estimate extent of slack – particularly in the labor market. Indeed, the likelihood is that additional fiscal and trade details due by the May MPC meeting, alongside the already frail real economy backdrop, may persuade the BoE into a further growth downgrade. Thus after the February cut we see at least three more moves this year and maybe four, we also see a similar pace and 75 bp of cuts through 2026. Indeed, the risk is if the economy continues to stagnate, cuts may come faster.

Sweden: Monetary Front Loading Nearly Done?

Sweden is very much part of the EU defense initiative, keen to underscore its military commitments with its first anniversary in joining NATO. But this is part of something that as far as Sweden is concerned is on-going as it signalled its increased defense appetite with a 10% jump in military spending in last September’s budget – NB: Sweden has one of the largest defense industries relative to the size of its population of any country, belying its status until recently of a neutral nation. Even so, this still pulls defense spending to 2.2% of GDP this year and while there is a path to push it up to 2.5%, this is only currently scheduled for 2029, the question being whether worries about Russia and inter-related EU pressure brings this timetable forward. However, with a general election due late next year, the Swedish government may use any fiscal space for policies more likely to win votes. As a result, a budget gap of around 1% of GDP this year (down from 1.5% in 2024) may halve next year and with the possibility of a further drop after 2026 as a parliamentary committee has proposed changing the net lending target level from the current surplus target to one of broad balance from 2027. Even so, the government debt ratio is unlikely to move much from the likely 33% of GDP outcome envisaged this year.

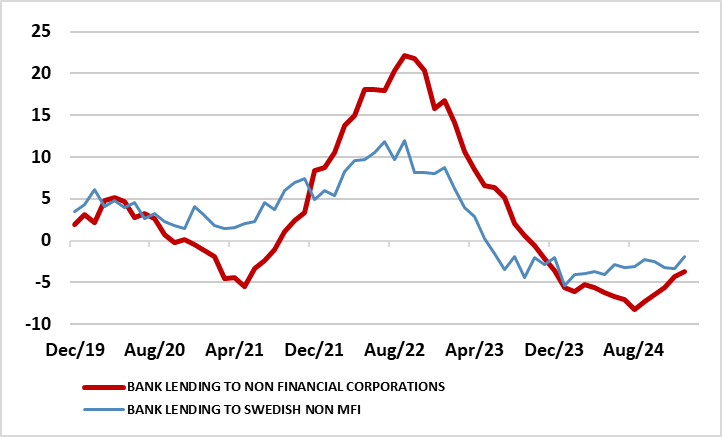

However, despite what seems to be a clear easing in fiscal policy now underway augmented by Riksbank rate cuts, the growth outlook still seems weak – NB monetary policy easing should bite relatively quickly in Sweden given that mortgages are still largely flexible rate driven. Indeed, we still point to a below-consensus 2025 GDP outlook of 1.5% despite a better than expected Q4 GDP reading and only a moderate further pick-up to 1.8% next year, both partly a result of the U.S. tariffs that will very likely hit all EU countries. Moreover, that outlook also comes with downside risks which encompass a consumer recovery next year that may be very feeble reflecting labor market uncertainty and what may be a sustained rise in household savings. There is also the fact that 2022-23 Riksbank tightening still seems to be biting given the continued marked and nominal fall in bank lending (Figure 3). Indeed, we think that the latter is a reflection of Riksbank policy also biting unconventionally as its balance sheet reduction, which had caused a marked drop in bank deposits (now only partly repaired) and where this weakness is affecting banks willingness/ability to lend.

In addition, external demand is projected to contribute less to economic growth over the forecast horizon partly as any domestic bounce may precipitate a recovery in imports, implying that the growth contribution from external trade is set to be relatively modest in 2025 and 2026. Thus also implies that a current account surplus that may narrow to well below 7% of GDP this year will continue to fall in 2026 toward 5%.

The consumer picture is made more uncertain as an unfolding sharp rise in unemployment should mean that wage growth this and next year may fall from last year’s 3.8%. As telling is the likelihood that housing construction (which has already fallen steeply due to lower house prices, higher construction costs and expensive financing) continues to contract into next year with an added negative now emerging in terms of much softer population growth. All of which could mean an output gap of over 1% emerging through into 2025 but one that should not get larger as we see near-trend growth of 1.8% in 2026.

This is only likely to reinforce the disinflation process, despite some upside surprises in CPI numbers of late but which are largely food and energy driven but this has pulled targeted inflation (CPI-ATE) back above the 2% target. But this has created a marked base effect and hence why we, alongside the Riksbank, see inflation slumping back in early 2026, although the mortgage rate induced base effects will offset much of this next year. Notably, recent data have shown clear signs of slowing services inflation in spite of the impact of rental inflation running at nearly 6%. Thus we adhere to our 2025 CPI projection of 1.6% and we see it staying below target through 2026 a picture that is now being acknowledged: inflation expectations two and five year measures are back at, or just below, pre-pandemic averages.

Figure 3: Bank Lending Still (Very) Negative

Source: Riksbank, % chg

As widely expected, policy was kept on hold at this month’s Riksbank Board meeting. Especially given the recent upside CPI surprises, this very much supported that Board assertion of a stable policy outlook from here-on reinforced by updated projections that continue to point to above-consensus growth this year and next. Indeed, it was notable was that little changed with largely stable projections for growth, output gap and even inflation, save on the latter for a spike higher now factored into this year but with a return to target from early 2026. But for the outlook, alongside further rate cuts from neighbouring central banks, we think this will trigger what may be a final Riksbank cut, not least if the current surge in the exchange rate persists. But any such further 25 bp reduction may be deferred until the June meeting, if not later!

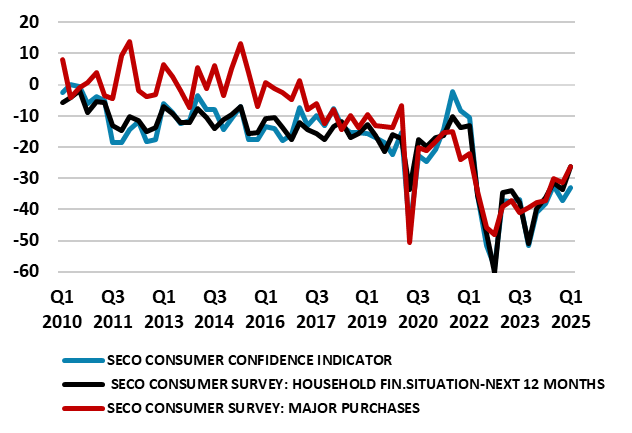

Switzerland: Consumer (Lack of) Confidence!

While far from unexpected, CPI inflation has fallen to levels seen prior to the pandemic, albeit not to the depth seen in the latter. But far from boosting consumer thinking, household sentiment remains historically and relatively low (Figure 4), reflecting continues worried about family finances, in turn, prejudicing spending plans. While we see inflation rising back in coming months, we wonder whether our largely unchanged CPI projections of 0.7% this year and still only 1.1% next will continue to weigh on consumer thinking as may a weaker labor picture in terms of much slower jobs growth. And the risks may be to the downside for inflation as it is noteworthy that weakness until this year was largely import price driven, but is now increasingly a result of weaker domestic goods and services, that have turned negative of late – at least on an adjusted m/m basis. The question is both whether this is a vicious circle in which inhibited consumers are becoming more and more price resistant, and where the latter may mean that solid 1.7% consumer spending backdrop of last year may slow meaningfully in 2025. In this regard, GDP numbers last year remained were also solid, but were boosted by sports events and unseasonable weather, effects that should unwind through 2025. Thus, an unrevised 1.0% this year is indicative of the economy is actually showing a below-par performance, but not markedly so. This will be as discernible in 2026 and where we have kept the GDP outlook at 1.3%, these numbers not too far below SNB thinking of 1.0-1.5% for 2025 and 1.5% for 2026. Partly the pick-up next year is a result of sports effects; partly a result of recent weakness in business investment easing, this a result of low industrial capacity utilization (Figure 4). But as far as this year is concerned, there also has to be a recognition of the soft backdrop we see in the Eurozone, as well as Switzerland not escaping US tariffs - most notably on its large pharmaceutical base. But also on the flip side in 2026, the extent to which the now likely German infrastructure and EU-wide defense initiatives spill over into Switzerland. This may be accentuated by construction staging clearer recovery amid some signs that the real estate market has passed the worst. Regardless, into 2025, these developments may help keep the current account surplus into 2026 above the circa-7.0% of GDP outcome we expect for this year.

Figure 4: Consumer Still Brooding?

Source: SECO, % balance

As for the policy outlook, the SNB cut the policy rate by 25 bp to 0.25% as widely expected earlier this month. In the policy assessment, the forecasts for inflation hardly changed, in contrast to the downward revisions in previous quarters. Notably the SNB highlighted that the CPI forecast is within the range of price stability (the SNB inflation target is purely for the rate to be below 2%) over the entire forecast horizon – all backing up our long-held view that the new current rate will be the policy trough and on a protracted basis!

However, this still leaves the SNB with a possible dilemma going forward. If the U.S. trade tariffs have a bigger adverse effect than expected, then the SNB may want the option to ease again later in the year. Additionally, the SNB will leave open the option of cutting to negative rates, just in case the Swiss Franc surges. The option of negative rates in itself meanwhile acts as a restraint from the FX market getting too bullish on the CHF. Thus SNB communications will likely leave the door open to further easing, but as suggested above we see this as probably the end to the easing cycle.

Norway: More Monetary Machismo

After a very solid Q3 GDP, the economy went into reverse last quarter. Thus, after a mediocre 0.6% outcome last year, well below expectations, the picture for 2025 is little better bit at as downgraded 0.8%, this below-consensus figure encompassing the continued pinch of (yet to be eased) monetary tightening alongside weak growth elsewhere in W Europe and beyond. Even so, it still represents decent q/q growth path with end year 2025 GDP growth a much perkier 1.4%. Even so, the ill omens are evident in the likes of a continued drop in real private sector credit growth which to us reflects activity continuing to decline in more rate-sensitive parts of the economy and that monetary policy is very restrictive. But higher defense spending is clearly on the fiscal agenda, this upside risk very much countered by trade threats even though Norway may not be as big a target for US tariffs aimed at the EU.

Obviously, inflation has surprised markedly on the upside of late, albeit mainly food and energy, all creating possible marked downward base effects for early 2026. And short-term dynamics are not nearly as worrying, especially in a core measure that excludes the food component (unlike the chosen policy measure of CPI-ATE). But as we have noted before inflation is bolstered by 4%-plus annual rental increases (19% of the CPI) which we think are policy pro-cyclical. For the reasons above, we think inflation will slow in due course – hence our unrevised forecast of 2% inflation next year more likely, albeit after an upwardly revised (by 0.7 ppt) to 2.7%.

Supporting this disinflation story, an improved productivity picture makes it more likely that an output gap may already have appeared and one that could enlarge through 2025 and persist in 2026. Admittedly, this may be inconsistent with a second successive year of negative fixed investment, and one that extends beyond weak construction, the latter very much likely to extend though the coming year. But in contrast to what we think is optimistic consensus thinking on household spending, we do not see any faster recovery than in 2024 and only modest growth next year broadly chiming with GDP. This is especially as the recent rise in house prices is fragile and unemployment is starting to rise although the jobless rate may just exceed 4% in 2025 and then stay there through 2026.

Figure 5: Disinflation Still but Less Clear

Source: Stats Norway, CE, smoothed = 3 mth mov avg

Norway sees the widely awaited Norges Bank decision later this month where recent inflation data have questioned whether the well flagged rate cut will now be delivered – we think the decision may be more finely balances that many are suggesting not least as economic activity signs are mixed even with the regional survey having improved. But inflation has moved further above target (see above), but has been boosted by a series of one-offs and also by the CPI basket re-weighting. The question is whether the (hawkish) Norges Bank judge price pressures appear to be more persistent than it previously assumed. Regardless, a significant reassessment, possibly including a deferment of the planned rate cut this week. As suggested the odds may be nearer balanced, but if pushed we see no change. Regardless, under any scenario, the rate path will be revised significantly higher.

As for that outlook, the Norges Bank worries about business costs envisage two-sided risks around it, encompassing the risk of an increase in international trade barriers but with less overt concern about the weak currency this time around. The worry is that higher tariffs will likely dampen global growth, but the implications for price prospects in Norway are uncertain. We still see some 100 bp of rate cuts in 2025 – ie likely to be more than 50 bp greater than the Norges Bank may be advertising in its looming policy assessment and at least the same amount of cuts in 2026!