Western Europe Outlook: Divergent Policy Thinking

· In the UK, perhaps the main story in our outlook is that we retain our below-consensus GDP picture for next year, with growth of 1.0% and with downside risks. The BoE will likely ease further through 2025 by at least 100 bp and maybe faster and beyond.

· As for Sweden, despite what has been a clear easing in both monetary and fiscal policy stances, the growth outlook still seems weak. Indeed, we have downgraded the 2025 outlook a further 0.3ppt to 1.0%.

· In Switzerland, GDP numbers this year have appeared more than solid, but rather than being indicative of above trend growth, the economy is actually showing a below-par performance, but not markedly so. Even so, the SNB may be almost done, easing wise!

· In Norway, we adhere to the 1.1% GDP picture for 2025, this below-consensus figure encompassing the continued pinch of (yet to be reversed) monetary tightening alongside weak growth elsewhere in W Europe and beyond. We, however, now see clear easing moves into 2025 possibly starting early in the new year.

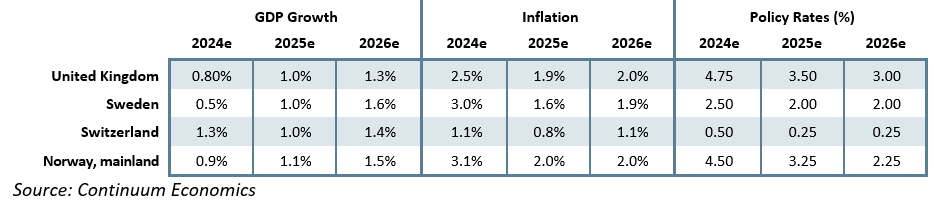

Forecast changes: Compared to our September Outlook, GDP growth forecasts have in most cases been downgraded2025. There is generally lower inflation envisaged this year, but where these we still suggest a durable return to (or below) central bank inflation targets into next year. Our policy outlook is little changed for 2025, showing slightly deeper cuts from the Riksbank and deferred easing by the BoE and Norges Bank!

Our Forecasts

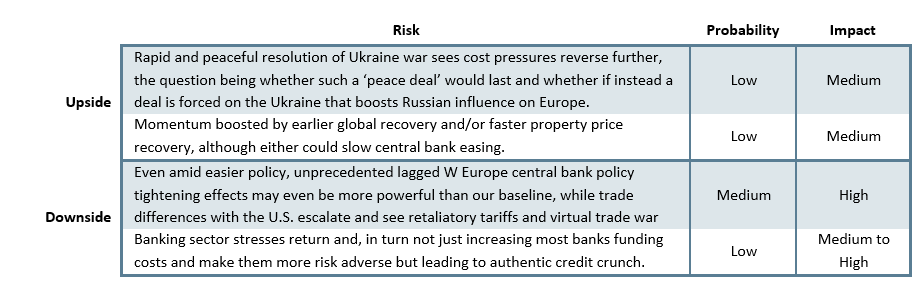

Risks to Our Views

Safe as Houses?

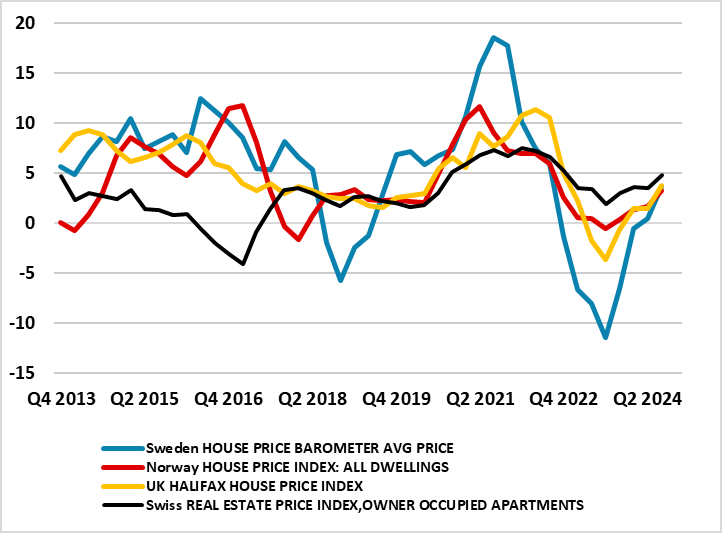

Not by design but more a coincidence, it is noteworthy that we have strikingly similar growth outlooks for all four W European economies for next year – the early sight of 2026 shows a slightly better growth but a similar convergence. Arithmetically, this is partly due to weak activity signals at the end of 2024 which have created mutually adverse base effects. But practically this actually reflects weakness in EZ spilling over across the continent. There is also another marked similarity in these economies, namely a recovery in residential house prices that have seen gains of around 3-4% y/y (Figure 1), a stark contrast to the weakness of a year earlier. This is all the more notable given a clear and seemingly increasing divergence among the West European central banks about policy, most notably in regard to the start and speed of monetary easing. This is in spite of what have been clearly and broad softer core inflation measures, particularly on a more up-to- date basis than lagging y/y rates. Most striking is the Riksbank as it has front-loaded policy easing, with the SNB following a similar path in terms of size and timing, both seeing scope and perhaps rationale for rates cuts from clear disinflation that occurred faster than the respective central banks has predicted.

Downside inflation surprises have also been the order of the day in Norway, at least until the most recent CPI release. But this does not seem to have persuaded the Norges Bank to any change in its cautious thinking. The Norges Bank is still grasped by currency concerns, hitherto steadfast that policy needed to be kept on hold for some time, it still suggests the first move may come in the new year. Given that the Norges Bank is still officially projecting persistently above target inflation this change in thinking does make it seem that it felt it was getting behind a curve compared to other DM central banks. Which leaves the BoE; it has more formally signaled it will ease further but only gradually, many interpreting this to mean at each of the quarterly Monetary Policy Report meetings ahead in 2025. But the BoE has over-estimated inflation even in the recent past and may be doing so at present, not least against the shadow cast by weaker global growth signs. Indeed, we think the BoE will ease faster next year than it has been hinting. However, the other key development for the UK policy outlook is that the BoE is also trying to implement the Bernanke Review, ie to alter its strategy and communications. In this regard it has already highlighted more formal scenarios for the inflation outlook, an upside and downside and a central case, the latter used as the basis for the MPR projections and encompassing more price pressures than envisaged in August. We wonder whether what may be long drawn out review may actually handicap actual policy making as the MPC wrestles with alternative policy outlooks and whether communication may thus suffer.

Figure 1: House Price Recovery Emerging on Broad Front?

Source: CE, % chg y/y

UK: Fragile Confidence?

Perhaps the main story in our UK outlook is that we retain our below consensus GDP picture for next year, with growth of 1.0% and with downside risks. This is in spite of the recent Budget delivering one of the largest fiscal loosenings in recent decades worth some 1% of GDP. But superimposed over this is the fact that Chancellor Reeves needed to make sure that the tax rises and added borrowing financing for this extra government spending did not have a protracted impact on activity via damage to sentiment. However, the national insurance rise could mean the Budget backfires and hurts the economy, something recent survey data cite. Indeed, while there is still an upside risk are that business may yet respond positively to the 2024election that delivered a stable government that is looking a less likely as the new administration faces the reality of actually being in power!

But there are also signs that some of the downside risks we have highlighted of late may actually have materialized especially as the economy has stalled since the spring, and may even contract in the current quarter. It thereby chimes with increasing weakness regarding employment and reflects an emerging and worrying loss of momentum in services, alongside more long-standing manufacturing weakness. Most notable is that lagged monetary policy effects may be biting harder than at least the BoE has factored in - the sizeable tightening has caused tighter financial conditions not only in terms of higher debt servicing but also increasingly in record high rent inflations. Indeed, policy is still biting the economy through the credit channel, where real credit growth in both is still negative.

Meanwhile, an added headwind is provided by a weaker overall European growth backdrop, most notably for the EZ and something that may already be evident in recent export weakness. Moreover, a good portion of the fiscal boost may end up boosting imports, which together with the fragile export picture alluded to above, possibly meaning that the wider current account deficit that 2024 will see (ie around 2.75% if GDP) may worsen into 2026. Furthermore, momentum of late has been partly dependent upon non-cyclical parts of the economy, in particular public services, which are likely to come under pressure from spending restraint certainly into 2026, if not earlier given growing risks that the weak growth backdrop may mean that the leeway in the new fiscal rules is used up. This all helps explain our 2026 GDP projection of no more than trend growth of 1.3%. In support of her high-profile pro-growth agenda, the Chancellor will hope that her non-Budget measures – the so-called seven pillars in the government long-term growth strategy – and a more pro-EU relationship will provide support but, if so, they will have to overcome what is a fragile backdrop in terms of confidence.

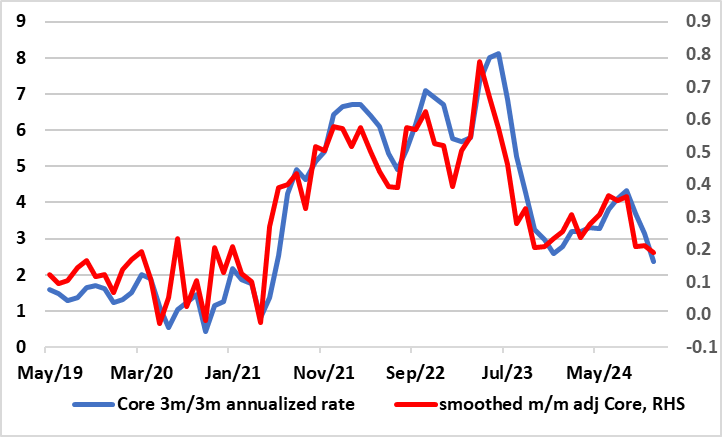

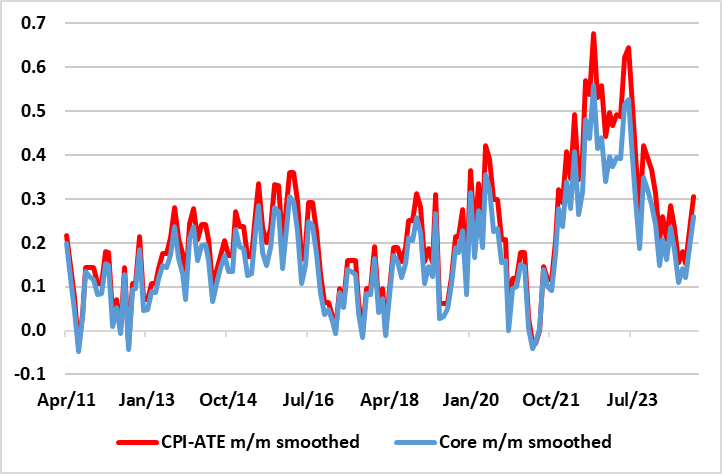

This below-par growth outlook into and through 2025, should add to the disinflation signs seen of late which we suggest hitherto have been a more a result of an easing in supply pressures. Indeed, excess supply is likely to open up into next year and may be even be as much as 1% of GDP in 2026. Thus, it is no surprise that CPI headline had fallen back to target and though energy swings have caused it to recover, it will then fall afresh and we still see it averaging below target in 2025 and staying there in 2026. Indeed, while recent CPI data have disappointed, the headline numbers have masked a clear fall in adjusted m/m price pressures (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Clear Adjusted Core Inflation Drop Intact?

Source: ONS, CE-computed seasonally adjusted core measures

Admittedly, there are still some apparently less ambiguous brighter signs regarding housing. But the level of transactions is still low, this being the main factor that will affect and weigh on consumer spending, through the year to a degree that very much risks the projected 0.7% rise this year not being bettered in 2025.

As for the BoE, the expected unchanged decision this month left Bank Rate at 4.75% but what was not foreseen was three dissents in favor of a cut with a further member advocating a more activist strategy. Overall, the BoE adhered to a gradual approach but with little forward guidance. But there were several less hawkish aspects to the statement, albeit where BoE thinking is clouded by added uncertainty over spare capacity. We think its gradualist approach is consistent with four 25 bp moves next year and we think there could be more. Given the evolving balance of risks, the three dissenters said a less restrictive policy rate was warranted and to us this very much points to a move at the next (Feb 2025) meeting. The question being twofold; whether the BoE then also hints at a more activist outlook as one MPC member pointed to and whether any clarity emerges about when/where policy stops being restrictive.

Sweden: Monetary Front Loading Nearly Done?

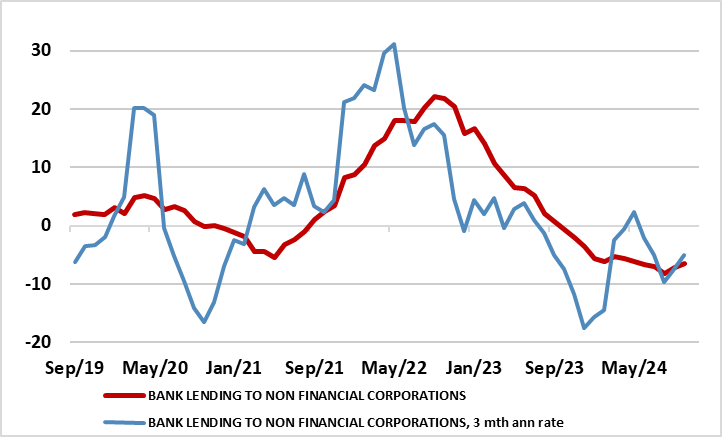

Despite what has been a clear easing in both monetary and fiscal policy stances the growth outlook still seems weak – NB monetary policy easing should bite relatively quickly in Sweden given that mortgages are still largely flexible rate driven. Indeed, we have downgraded the 2025 GDP outlook a further 0.3 ppt to 1.0% despite a better than expected Q3 GDP reading, albeit the latter not enough to have prevented the picture for this year being shaved a notch to 0.5%. Notably, while the consensus is somewhat higher for next year, it too has been pared back of late, this largely a result of poor economic news both domestically and nearby as far as Sweden is concerned. Indeed, that seemingly positive Q3 GDP reading was based almost solely around an inventory build that looks suspiciously involuntary enough to unwind into 2025. Indeed, that 2025 outlook also comes with downside risks which encompass a consumer recovery next year that may be very feeble reflecting labor market uncertainty and what may be a sustained rise in household savings. There is also the fact that 2022-23 Riksbank tightening still seems to be biting given the continued marked and nominal fall in bank lending (Figure 3) evident in much shorter periods than just y/y rates too. Indeed, we think that the latter is a reflection of Riksbank policy also biting unconventionally as its balance sheet reduction, which has caused a marked drop in bank deposits of almost 3% in the last year alone and where this weakness is affecting banks willingness/ability to lend.

In addition, external demand is projected to contribute less to economic growth over the forecast horizon partly as any domestic bounce may precipitate a recovery in imports, implying that the growth contribution from external trade is set to be relatively modest in 2025 and 2026. Thus also implies that a current account surplus that may narrow to just below 7% of GDP this year will continue to fall in both 2025 and 2026 toward 5%.

The consumer picture is made more uncertain as a rise in unemployment should mean that wage growth this and next year may fall from last year’s 3.8%. As telling is the likelihood that housing construction (which has already fallen steeply due to lower house prices, higher construction costs and expensive financing) continues to contract into next year. All of which could mean an output gap of over 1% emerging through into 2025 but one that should not get larger as we see near-trend growth of 1.6% in 2026.

This is only likely to reinforce the prices situation where more signs of disinflation continue to amass, and broadly so. Indeed, targeted inflation (CPI-ATE) is below the 2% target. But this has been very evident in seasonally adjusted m/m core CPI readings which have showed a much softer profile prior for some time. Notably, this includes clear signs of slowing services inflation. Even though we have revised our 2025 CPI projection up by 0.1 ppt next year to 1.5% (a result of the EU’s new electricity directive which has caused a sharp increase in electricity prices), we see it staying below target through 2026 a picture that is now being acknowledged: inflation expectations two and five year measures are back at, or just below, pre-pandemic averages.

Figure 3: Bank Lending Still (Very) Negative

Source: Riksbank, % chg y/y

As widely expected, a fifth successive rate cut was seen at this month’s Riksbank meeting, but back to a 25 bp move (to 2.5% vs the 4% peak seen up until last May). But it was the updated projections that was be the main news, not least given data of late that has been on the high side of expectations, including a small recovery in GDP and CPIF data well above Riksbank thinking. In this regard, the Riksbank did revise down its slightly above-consensus GDP outlook out to 2027, whilst still suggesting inflation will settle around target. Perhaps the question was whether a lower terminal policy rate was considered, but this does not seem to be the case with one more 25 bp reduction penciled in for H1 next year and then with the ensuing policy rate staying there out to 2027. But amid downside growth risks and realties through Europe, we still see the policy rate troughing at 2.0% by mid-2025, but still well within the range that the Riksbank has for its’s terminal rate estimate. But deeper cuts are possible as even the Riksbank acknowledges, albeit with policy reverting back to the baseline ultimately.

Switzerland: SNB Still Seeing Inflation Undershoot

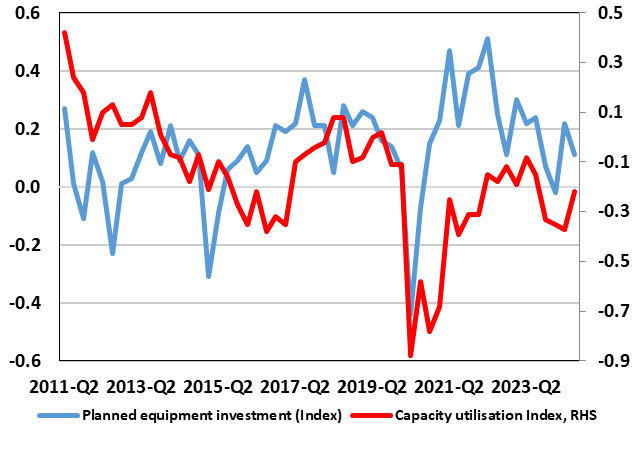

GDP numbers this year have remained more than solid, but have been boosted by sports events effects and unseasonable weather, effects that should unwind through 2025. Thus, at an unrevised 1.3% this year, rather than being indicative of above trend growth, the economy is actually showing a below-par performance, but not markedly so. This will be more discernible in 2025 and we have pared back the outlook by 0.2 ppt to 1.0%. Partly this a result of sports effects; partly a result of recent weakness in business investment persisting, this a result of low industrial capacity utilization (Figure 4) and also weak order books. But there also has to be a recognition of the more marked weakening we see in the Eurozone, and particularly Germany, the impact of which is already showing up in terms of fresh drops in Swiss manufacturing (20% of GDP). This may be accentuated as pharmaceutical demand continues to normalize and construction is also likely to remain fragile into 2025, even amid some signs that the real estate market has passed the worst. But there are also more domestic risks in the form of weaker labor market (most notably an almost stalling in employment) which suggest consumer spending is now likely to grow slower than GDP but still enough to fuel import growth that matches that of exports. The consumer picture is puzzling though, given that survey data suggests downbeat sentiment and continued wariness about elevated prices – these conflicting with recent reality.

Regardless, into 2025, these developments may help keep the current account surplus into 2026 above the 7.0% of GDP outcome we expect for this year.

Import trends are also helping weigh on prices but are not the only factor. Perhaps somewhat excessively, much of recent inflation weakness has hitherto been attributed (at least by the SNB) to the strong Swiss Franc, but where we have suggested weaker global and domestic demand has been also playing a part and will continue to do so. Indeed, we have pared back our CPI forecast for next year to just 0.8% down from 1.2%, a projection about twice that of the SNB. This continues to reflect still limited wage pressures and unusual mix of services in the CPI basket. Indeed, recent actual inflation dynamics certainly suggest disinflation continues and we see inflation just above 1% on average for 2026.

Figure 4: Capex Climate Still Cool

Source: SNB Company Talks Survey, % balance indexes

As for the policy outlook, in what seems to be ever-clearer policy front-loading, the SNB cut its policy rate this month by 50 bp (to 0.5%), thereby accentuating an easing cycle that had delivered three 25 bp moves since March. Possibly, this larger, but far from unexpected, reduction was driven by a fresh assessment that the inflation undershoots (both that seen of late and that projected out to 2027) are indeed increasingly a reflection of weaker underlying price pressures rather than currency induced disinflation. But notably, and despite the marked anticipated inflation undershoot, the SNB seemed less explicit this time around about further cuts, save to repeat its long-standing mantra that it ‘will adjust its monetary policy if necessary to ensure inflation remains within the range consistent with price stability over the medium term’. Possibly, and maybe reflecting recovery property prices, this could signal a policy pause, but we still see another 25 bp cut in Q1 next year.

Norway: More Monetary Machismo

A very solid Q3 GDP has prompted an upgrade to the growth backdrop for 2024 (by 0.3 ppt) to 0.9%. But we adhere to the 1.1% picture for 2025, this below-consensus figure encompassing the continued pinch of (yet to be eased) monetary tightening alongside weak growth elsewhere in W Europe and beyond, the former highlighted by a continued drop in real private sector credit growth. Notably, this comes after recent national account revisions which have shown much stronger GDP growth in the last few years, but also alongside a weaker backdrop for hours worked. This implies a much better productivity picture which we think reinforces - and helps explain - what is already a very visible disinflation climate, most clearly as an offset to a wage picture that may see increases above 4% in 2025, after around 5% this year. Admittedly, the most recent set of CPI figures disappointed somewhat but have not really altered what has been a clear downtrend in whatever underlying gauge one chooses that are being masked by over reliance on y/y rates (Figure 5 show m/m adjusted data for the targeted CPIF as well as our compilation of a core). Moreover, even these measures are being bolstered by 4.5% annual rental increases (18% of the CPI) which we think are policy pro-cyclical. Indeed, ex-rent inflation is running at around the 2% CPI target, which makes our forecast of 2% inflation both next year and in 2026 hardly out of order; in fact, we see the targeted CPI-ATE measure hitting 2% in H1 next year.

In addition, the productivity picture makes it more likely that an output gap may already have appeared and one that could enlarge through 2025 and persist in 2026. Admittedly, this may be inconsistent with a second successive year of negative fixed investment, and one that extends beyond weak construction, the latter very much likely to extent though the coming year. But in contrast to what we think is optimistic consensus thinking on household spending, after a clear fall in consumer spending last year, we do not see any recovery in 2024 and only modest growth next year broadly chiming with GDP. This is especially as the recent rise in house prices is fragile and unemployment is starting to rise although the jobless rate may just exceed 4% in 2025 and then stay there through 2026.

Figure 5: Disinflation Still Clear

Source: Stats Norway, CE, smoothed = 3 mth mov avg

An eighth successive stable policy decision was forthcoming at this month’s Norges Bank decision so that the policy rate at 4.5% has been in place for a year. The statement was more open about policy being eased but only after two more meetings, so that the first cut will come in March next year. The revised forecasts saw higher growth numbers but where the inflation outlook shaved back somewhat amid what was termed inflation pressures that appear to have been slightly more subdued than previously assumed. But the worry about business costs actually saw the policy outlook raised slightly, but with two-sided risks around it, encompassing the risk of an increase in international trade barriers but with less overt concern about the weak currency this time around. The worry is that higher tariffs will likely dampen global growth, but the implications for price prospects in Norway are uncertain. The scheduled decision on Jan 23 could still see the first rate cut, although this is now less likely. We still see some 125 bp of rate cuts in 2025 – ie 25 bp to 50 bp more than the Norges Bank is advertising!