Western Europe Outlook: The First Shall be Last…

· In the UK, we have upgraded 2025 growth by 0.3 ppt back to 1.0%. But this is purely a result of the Q1 front-loading and instead masks what we think will be essentially a flat GDP profile into 2026. The BoE will likely ease further in H2 by at least 50 bp and maybe faster and then into 2026 too.

· Sweden has seen a clear easing in both monetary and fiscal policy stances, but the growth outlook still seems weak and where the Riksbank’s activity optimism still looks overdone, probably meaning a little further policy easing from the latter can be expected.

· In Switzerland, the most recent GDP numbers have appeared more than solid, but this masks a softer underlying picture that will be more discernible in a below-par performance into 2026, but not markedly so. Even so, the SNB is most likely done, easing wise unless already soft inflation turns more negative.

· In Norway, after a mediocre 0.6% GDP outcome last year, the picture for 2025 is only a little better at a downgraded 0.8%, this below-consensus figure encompassing the continued pinch of (yet to be eased) monetary tightening alongside weak growth elsewhere.

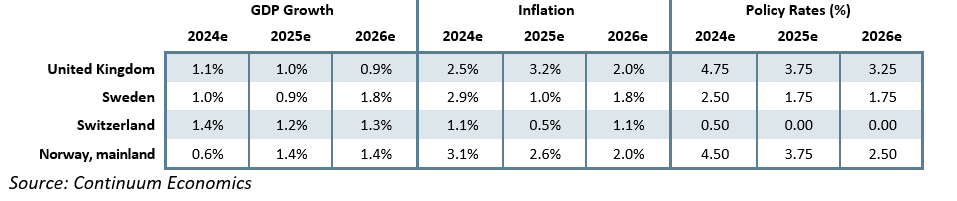

Forecast changes: Compared to our March Outlook, 2025 growth forecasts have been largely upgraded due to Q1, with Sweden the notable exception. Some would suggest that, surprisingly, this better 2025 backdrop comes with downward CPI revisions except for the UK, this also forcing a revised policy outlook. Regardless, we still suggest a durable return to (or below) for all central bank inflation targets into next year so that our policy outlook is little changed for end-2026; Sweden and Switzerland a notch lower, the UK and Norway a notch higher!

Our Forecasts

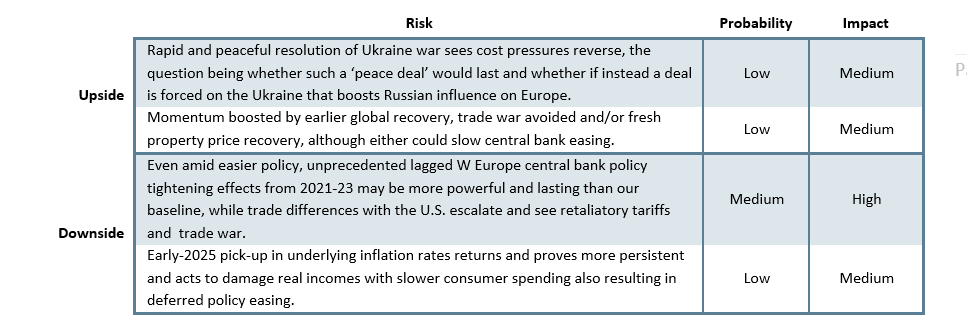

Risks to Our Views

Source: Continuum Economics

Coming Late to the Easing Party?

Belatedly, all four W European central banks have now entered into the monetary policy easing party, the Norges Bank being the notable latecomer, so late in fact that the Riksbank and SNB may already have left the room by now (almost) ending their respective rate cut cycles. Meanwhile, the BoE is the only central bank that is also pursuing outright sales of its bond portfolio as part of its quantitative tightening program; the BoE looks to be in the middle of a gradual cycle. This is partly a result of what has been a rise in UK inflation based around regulated and energy prices, that has surprised on the upside somewhat and come alongside the very opposite in CPI moves elsewhere. This is perhaps most discernible in terms of Swiss inflation where core adjusted m/m numbers have dropped towards a zero trend of late and where similar trends are emerging for both Norway and Sweden (Figure 1). This inflation divergence has little to do with deviating growth backdrops as Q1 saw a solid GDP q/q outcome in all but Sweden (the result being the ensuing upgrades to 2025 GDP projections except for Sweden).

But there are still similarities in some aspects in all four economies. Firstly, a broad recovery in residential house prices that has seen gains in excess of 3-4% y/y, although this too may be fading if not reversing. Secondly, has been the creation of sizeable base effects that should pull targeted inflation down in H1 2026. This partly the impact of the usual re-weighting of CPI baskets that national statistical offices carry out usually at the beginning of each year but also due to fiscal swings in the UK and where the UK may be exception as it alone may see a swing towards budgetary restraint into 2026 – and beyond.

Figure 1: Core Price Pressures Drooping – Nearly Everywhere?

Source: CE, seasonally adjusted core m/m rates, 3 mth moving average

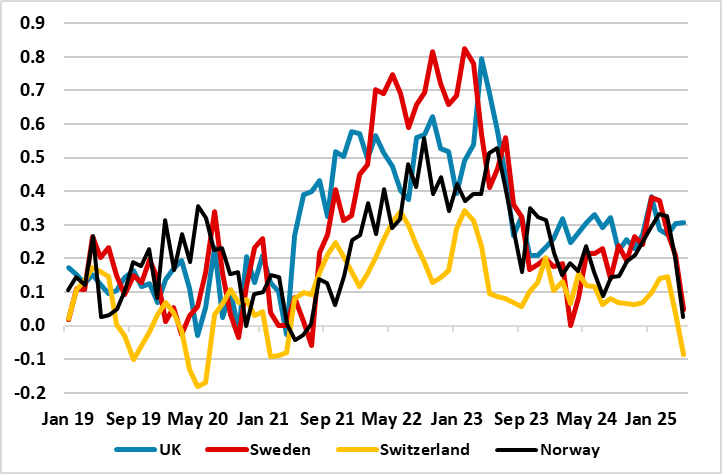

UK: A Tale of Two Economies?

The forecasts that we are updating here, as always are tinged with uncertainties. But in the UK at the moment forecasting is made all the more difficult as we are almost as unsure as to the starting place let alone how activity may pan out. This reflects disparities and divergences in various and alternative forms of data. In particular, GDP grew by a strong and unexpected 0.7% in Q1, largely due to an export jump in anticipation of tariffs, this nevertheless creating an appearance of economic resilience if not recovery. But other data very much unambiguously point in the opposite direction (Figure 2). Admittedly, it could be argued that amid such ambiguity it would be best to take a middling view, ie not to be too influenced by either extreme. The problem with this is that the bulk of alternative data side with the (much) weaker growth story and outlook and increasingly so. Indeed, the softer survey data chime with increasing weakness regarding private sector employment and government borrowing exceeding forecasts and now with retail data suggesting that Q2 may see a q/q drop (this being in contrast to the upgraded 0.25% projection the BoE has just unveiled). It also reflects an emerging and worrying loss of momentum in services, alongside more long-standing manufacturing weakness. Most notable is that lagged monetary policy effects (both conventional and unconventional may be biting harder than at least the BoE has factored in). Indeed, policy is still biting the economy through the credit channel, where real credit growth is still negative.

Thus, regarding our UK outlook, while we have upgraded the expected growth by 0.3 ppt back to 1.0%, this is purely a result of the Q1 front-loading. Instead, it masks what we think will be essentially a flat GDP profile into 2026. And there are downside risks given the growing evidence that the tax rises and added government borrowing has caused damage to economic sentiment. Indeed, the recent national insurance rise is already reverberating in terms of business and consumer confidence with the likelihood that the fiscal update due in the autumn will see more tax hikes/spending cuts to add to the welfare bill reduction already flagged; a sizeable further fiscal reversal may be needed to provide a credible repair to ensure the fiscal rules. Admittedly, defense spending is being raised but in budget neutral capacity as overseas aid has been cut to finance the initiative.

All of which to us means that this year consumer spending may not exceed the 0.6% growth set last year. Meanwhile, an added headwind is provided by a weaker overall European growth backdrop, most notably for the EZ although this may be more short-lived that previously envisaged given the fiscal and defense initiative the EU is trying to put together. The U.S. tariff threat also remains even though it has been reduced somewhat by the framework trade deal - but the UK will not escape the global fall-out. Regardless, we see imports recovering, which together with the fragile export picture, points to a wider current account deficit than that seen in 2024 (ie around 2.75% of GDP) into 2026. Furthermore, momentum of late has been partly dependent upon non-cyclical parts of the economy, in particular public services, which as suggested above are likely to come under pressure from spending restraint certainly into 2026, if not earlier. This all helps explain our downgraded 2026 GDP projection of 0.9%, this having been revised down 0.3 ppt. In support of her high-profile pro-growth agenda, the Chancellor will hope that her non-Budget measures – the so-called seven pillars in the government long-term growth strategy – and a more pro-EU relationship will provide support but, if so, they will have to overcome what has been a dent to the government’s stability aspiration.

This below-par growth outlook into and through 2025, should add to the disinflation signs seen of late which we suggest hitherto have been a more a result of an easing in supply pressures. Indeed, excess supply is likely to open up into next year and may be even be as much as 1% of GDP in 2026. Thus, it was no surprise that CPI headline fell back to target even if proved short-lived. Instead, a raft of one-off factors has pushed inflation back higher and this will persist for the bulk of the year. As a result, inflation may now average around 3.2% in 2025, some 0.5 ppt higher than previously thought. Regardless, we still see a 2026 outlook with a little changed 2.0% projection.

Figure 2: An Array of Data Now Pointing South!

Source, ONS, Markit HMRC

As for the BoE, even with policy on hold this month, a shift in thinking seems to be occurring reflecting a ‘material further loosening in labour market conditions’. Regardless, the official guidance still points to the need for policy to be framed carefully as well as gradually, also repeating that monetary policy will need to continue to remain restrictive for sufficiently long – the question being whether the dissenters also reject this line of thinking. We think that with the BoE regarding neutral policy rate as being well above 3%, two further 25 bp moves this year will be followed by another 50 bp in H1 2026. But we think the risks are for deeper and possibly faster cuts as we think the BoE is both over optimistic about growth prospects and over-estimating policy neutrality. One question here is if the BoE slows its QT program will this have any bearing on conventional policy – we think that the MPC in September will likely slow its annual rundown of gilts from GBP 100bln pa to GBP 75bln (here).

Sweden: Much Softer Growth Backdrop?

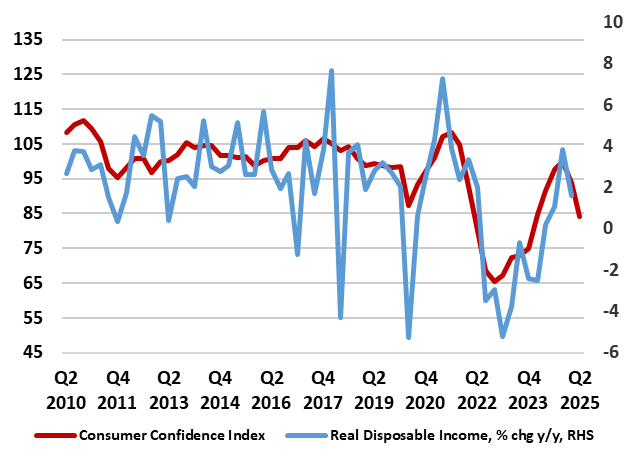

A weak first quarter, and comprehensive revised national account numbers, have prompted a marked downgrade to even our below consensus thinking, especially for this year. Indeed, we now point to a below-consensus 2025 GDP outlook of 0.9% (0.6 ppt below what we envisaged three months ago) and a moderate pick-up to 1.8% next year, both partly a result of the U.S. tariffs that will very likely hit all EU countries. Moreover, that outlook still comes with downside risks which encompass a consumer recovery next year that may be very feeble reflecting a clearly rising jobless rate which may even approach 9% into 2026 and which should mean that wage growth this and next year may fall from last year’s 4%. In fact, it is notable, that many firms have ample spare capacity and can therefore increase output without hiring new staff. As a result, the tentative recovery in household disposable income could yet stall, this explaining at least partly weak consumer confidence (Figure 3). There is also what is already a sustained rise in household savings and also the fact that 2022-23 Riksbank tightening still seems to be biting given the continued marked and nominal fall in bank lending. Indeed, we think that the latter is a reflection of Riksbank policy also biting unconventionally as its balance sheet reduction is still affecting banks willingness/ability to lend.

In addition, external demand is projected to contribute less to economic growth over the forecast horizon partly as any domestic bounce may precipitate a recovery in imports which actually fell in 2024, implying that the growth contribution from external trade may be slightly negative in 2025 and 2026. This also implies that the current account surplus may narrow to well below 7% of GDP this year and in 2026 toward 5%.

Sweden is very much part of the EU defense initiative, keen to underscore its military commitments with its recent joining NATO. But this is part of something that as far as Sweden is concerned is on-going as it signalled its increased defense appetite with a 10% jump in military spending in last September’s budget – NB: Sweden has one of the largest defense industries relative to the size of its population of any country, belying its status until recently of a neutral nation. Even so, this still pulls defense spending to 2.2% of GDP this year and while there is a path to push it up to 2.5%, this is only currently scheduled for 2029, the question being whether worries about Russia and inter-related EU pressure brings this timetable forward. However, with a general election due late next year, the Swedish government may use any fiscal space for policies more likely to win votes. As a result, a budget gap of around 1% of GDP this year (down from 1.5% in 2024 which partly reflect special payments to the Riksbank) may halve next year and with the possibility of a further drop after 2026 as a parliamentary committee has proposed changing the net lending target level from the current surplus target to one of broad balance from 2027. Even so, the government debt ratio is unlikely to move much from the likely 33% of GDP outcome envisaged this year.

Otherwise, is the likelihood that housing construction (which has already fallen steeply due to lower house prices, higher construction costs and expensive financing) continues to contract into next year with an added negative now emerging in terms of much softer population growth. All of which could mean an output gap of possibly over 2% emerging through into 2025 but one that should not get larger as we see near-trend growth in 2026.

This is only likely to reinforce the disinflation process, now made more manifest by a series of downside surprises in CPI numbers of late. But the upside surprises earlier this year have created a marked base effect and hence why we, alongside the Riksbank, see inflation on this basis slumping back in early 2026. Notably, recent data have shown clear signs of slowing services inflation in spite of the impact of rental inflation still running at nearly 5%. Thus we reduced our 2025 CPI projection from 1.6% down to 1.0% and we see it staying below target through 2026 although the mortgage rate induced base effects will pull it higher next year. Regardless, this picture is now being acknowledged: inflation expectations measures are back at or below target and pre-pandemic averages.

Figure 3: Consumer Worries Based Around Weak Income Growth

Source: Stats Sweden

As widely expected, the Riksbank cut its policy rate by a further 25 bp to a new cycle low of 2.0% this month. Moreover, the Board even then suggest that a further move is possible. Given that even with substantial paring back of its growth forecasts and with an ensuing revision that now sees a substantial output gap, we are puzzled that there was no appreciable downgrade to the inflation outlook. Instead, while we see CPIF inflation falling below target by next year we think the economy will under-perform the 1.2% and 2.4% GDP projections for this year and next and that this will make the Riksbank have to react and deliver the half-hearted rate cut it is flagging, probably next quarter to 1.75% which we then see staying in place into 2027.

Switzerland: Consumer (Lack of) Confidence Continues

The Swiss economy is very exposed to global trade with exports representing some 68% of GDP and goods exports alone some 48% and where some 2%-plus of Swiss GDP comes from exports to the U.S. Thus the 10% tariff the US has already imposed is a clear risk, as is that from the threat of it both being raised and added to via a 25% levy on pharmaceuticals. The latter sector represents some 7% of Swiss GDP (ie a larger share than the infamous financial sector) and where the bulk of pharmaceutical exports are to the U.S. Even so, we feel at this juncture that our semi-consensus and below-trend GDP outlook of 1.2% and 1.3% growth this year and next (the former revised higher and the latter downgraded slight compared to three months ago), is valid albeit with activity subject to a correction back in the near-term as the huge tariff-anticipating export surges that have boosted growth in the last two quarters reverse.

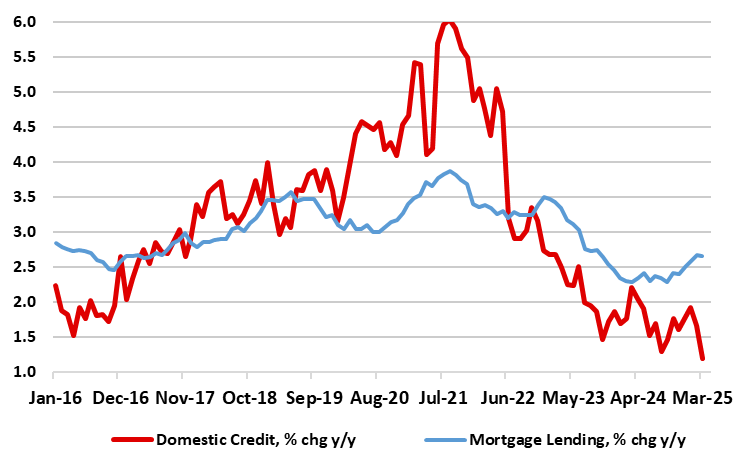

It is also possible that the tariff threat is making banks wary about lending, this possibly explaining fresh weakness in private sector credit, especially outside of mortgages (Figure 4). But the tariff threat also poses a clear disinflationary risk both from somewhat more subdued demand but also from displaced exports that would have gone to the U.S. And for Switzerland, this will merely add to disinflation pressures increasingly evident at home. To many, the strong Franc poses the clearest such disinflation pressure, but this is only partly responsible for imported consumer goods inflation now running below -2% y/y. But perhaps the greater threat, at least now emerging, is from domestic goods inflation. This is running at just 0.8% y/y, having more than halved in the last six months. But this masks even clearer domestic disinflation of late with adjusted m/m data suggesting that it now running at around zero, actually softer than the main core CPI measure. This therefore means that the SNB faces a triple disinflation threat ahead; from abroad via tariffs and the exchange rates but also now and increasingly at home. Admittedly, the SNB’s inflation target offers flexibility in that it merely stipulates inflation below 2%, but the prospect of persistent negative headline inflation is not one the SNB will take lightly.

But far from boosting consumer thinking, weak inflation is still seeing household sentiment remain relatively low, reflecting continued worried about family finances, in turn, prejudicing spending plans. The question is whether this is a vicious circle in which inhibited consumers are becoming more and more price resistant, and where the latter may mean that solid 1.7% consumer spending backdrop of last year may slow meaningfully in 2025. As for overall GDP, partly the pick-up next year is a result of sports effects; partly a result of recent weakness in business investment easing, this a result of low industrial capacity utilization and where end-2026 growth may be a more sizeable 1.6%. But as far as this year is concerned, there also has to be a recognition of the soft backdrop we see in the Eurozone, as well as Switzerland not escaping US tariffs. But also on the flip side into 2026, the extent to which the now likely German infrastructure and EU-wide defense initiatives spill over into Switzerland. This may be accentuated by construction staging clearer recovery amid some signs that the real estate market has passed the worst. Regardless, into 2025, these developments may help keep the current account surplus into 2026 around the circa-5.5% of GDP outcome we expect for this year.

Figure 4: Weak Credit Growth a Sign of Bank Caution?

Source: SNB

As for the policy outlook, the SNB cut the policy rate by 25 bp to zero this month, as widely expected. The SNB would probably prefer to consolidate the effects of previous rate cuts, but the still low inflation forecast and downside risk to inflation means that a cut to -0.25% is feasible at the September or December meetings with the policy rate then staying in place at least through 2026. The SNB will also hope that the threat of negative rates restrains the CHF strength and perhaps also encourages banks to lend.

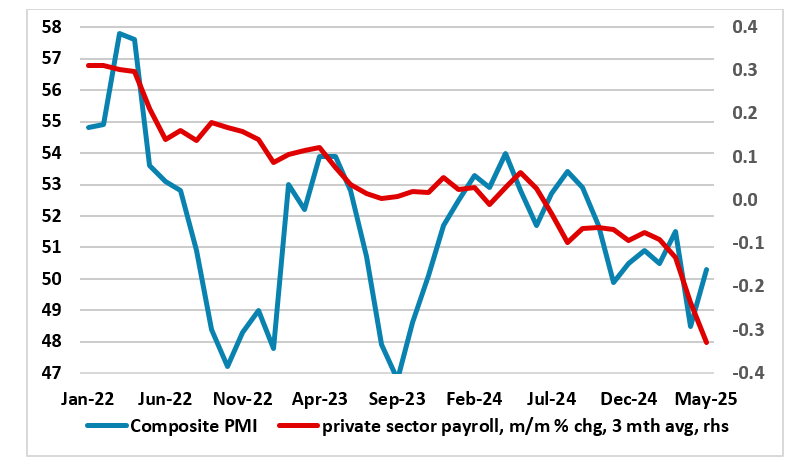

Norway: Economy Surprises in Both Directions

The economy (both real and nominal) has been volatile so far this year. Indeed, mainland GDP climbed 1.0% q/q in Q1, the strongest such outcome for almost three years, with no sign that the bounce was a result of tariff anticipation seen in other European economies. However, CPI data has surprised in the opposite direction more recently; in fact, CPI inflation has been persistently below Norges Bank’s expectations. And as Figure 1 shows core inflation (ie the former ex food) is running nearer zero on an adjusted and smoothed m/m basis.

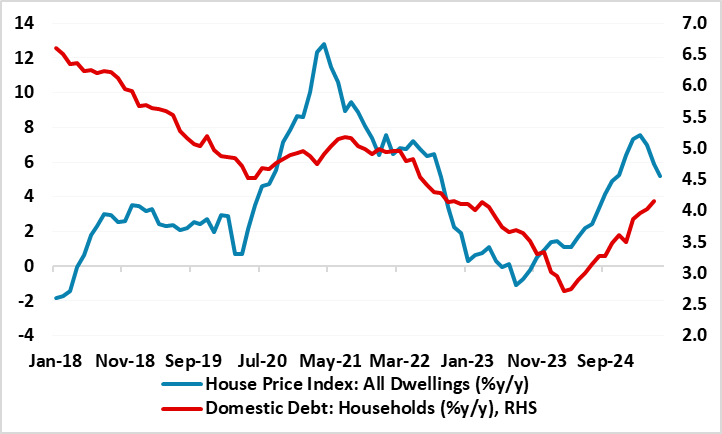

But returning to the real mainland economy, there are several factors we see restraining growth over the course of the year and into 2026. First, oil investment has peaked and this will filter through even into the mainland economy, this also likely to see the current account deficit fall from to around 15% of GDP this year – it also means that overall GDP may grow by less than 0.5%. Secondly, in what has been solid growth in interest-rate-sensitive sectors such as private consumption and housing investment this may have reflected what were widespread expectations of a rate cut in March that never materialized. Notably more recent data does suggest some reversal is occurring (Figure 5), especially in housing – the question being whether the surprise Norges Bank cut this month revives activity. Thirdly, global trade conflicts will hit Norway even though exports to the U.S. make up only about 8% of mainland exports, but where the indirect effects may be more pronounced, of course.

Regardless due to the Q1 outcome, the picture for 2025 is much better at an upgraded 1.4%, this slightly above-consensus figure also encompassing the continued pinch of (yet to be eased) monetary tightening alongside weak growth elsewhere in W Europe and beyond. These will also affect 2026 where we expect similar growth (this revised down a notch compared to three months ago).

As for inflation we have scaled back the CPI outlook by only a notch for this year to 2.5% but still see a return to target though 2026 – after all, and as suggested above, this would be merely an extrapolation of recent m/m adjusted trends. Indeed, on balance, we still see disinflation. Lower growth in unit costs will put a damper on domestic inflation, and lower global price increases combined with a more stable NOK will put a damper on imported inflation. Moreover, rent increases are slowing due to lower inflation, and increased activity in the secondary housing market. NB; CPI inflation has been being bolstered by 4%-plus annual rental increases (19% of the CPI) which we think are policy pro-cyclical.

Supporting this disinflation story, an improved productivity picture makes it more likely that an output gap may already have appeared and one that could enlarge through 2025 and persist in 2026 – this being a view that Norges Bank now seem to accept. But in contrast to what we think is optimistic consensus thinking on household spending, we do not see any faster growth than in 2024 and only modest growth next year broadly chiming with GDP. This is especially as, and as suggested above, the recent rise in house prices is fragile and unemployment is starting to rise although the jobless rate may just exceed 4% in 2025 and then stay there through 2026.

Figure 5: Housing Momentum Reversing?

Source: Stats Norway

Although we thought the Norges Bank would not start to ease until its next (Aug) meeting, we think the surprise 25 bp policy cut (to 4.25%) announced this month was very much warranted, as are the further cuts being flagged in the updated Monetary Policy Report (MPR) – ie two more such moves by end year. Perspective is needed as the Norges Bank was the first DM central bank to start hiking and is now the last to start easing. Obviously, it has been swayed by better CPI data (see above) as well as by a more stable exchange rate, and perhaps a realization that amid the downside risks facing the European economies it is better to take out policy insurance sooner than later. However, the Norges Bank is trying to suggest that it is merely reducing current policy restrictiveness, but it is clear that it sees somewhat more spare capacity than hitherto. We see up to two further 25 bp moves this year and around a full ppt more in 2026.