BOE QT: Slowdown in September?

BOE QT is part of the reason behind both a steeper yield curve and subdued M4 and lending growth. The MPC in September will likely accept that to avoid impacting the monetary transmission mechanism that annual rundown of gilts needs to be slowed from GBP100bln pa to GBP75bln. Internal differences within the MPC argue against a more aggressive slowing.

With the Fed having quickly slowed QT, could the BOE also slow QT in September?

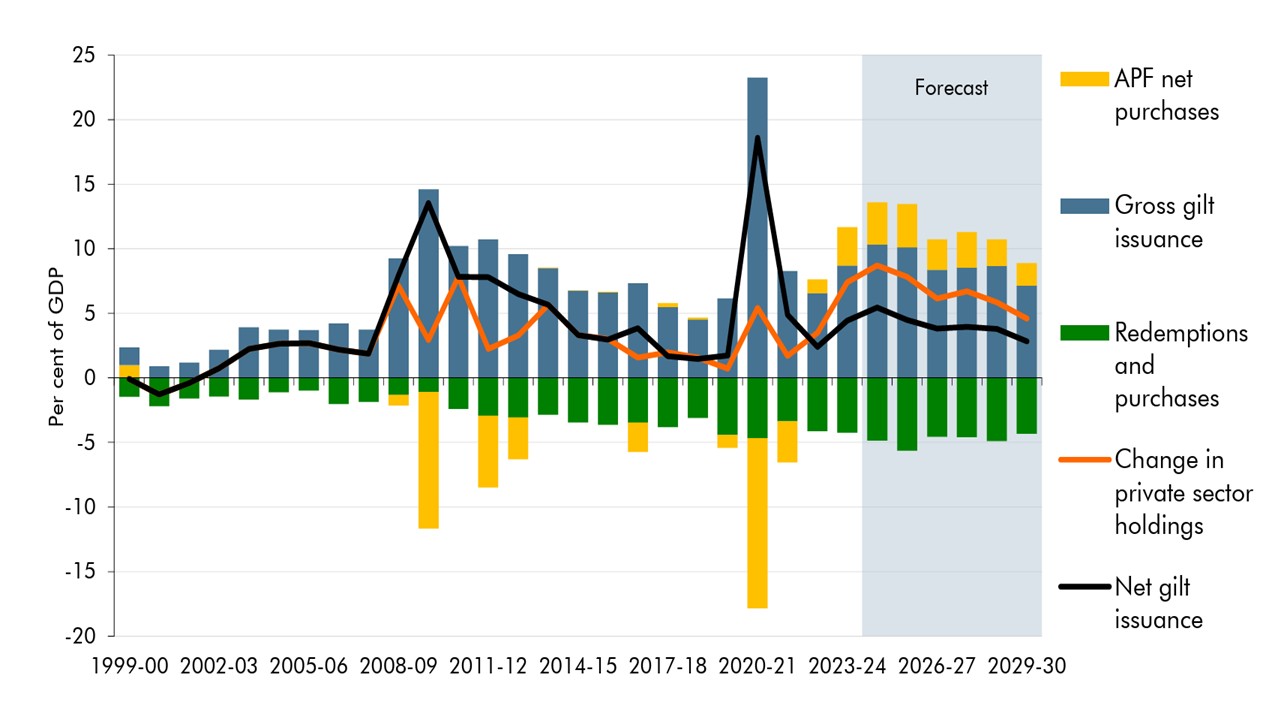

Figure 1: M4 and Net Lending (Yr/Yr %)

Source: Datastream/Continuum Economics.

The MPC main worry is epitomized in its various scenarios regarding the scale and speed of any slowdown of service and wage inflation, which is leading to splits on interest rate decisions. However, recent employment data shows a sharp fall (here) and a worse labor market than the U.S. or EZ and this will likely lead to downside surprises on service and wage inflation in the coming quarters. One of the problems is that the MPC is not taking account of the tightness of UK monetary conditions across the yield curve.

Firstly, the BOE MPC has a weakness in money supply analysis, as it places little weight on the current subdued trend of M4 and net lending growth (Figure 1). Credit supply is not really a problem with well capitalized banks, but rather credit demand is soft. The lagged effects of the 2021-23 tightening cycle are still coming through, as households and companies find that debt rollovers are at much higher borrowing rates than the post GFC period.

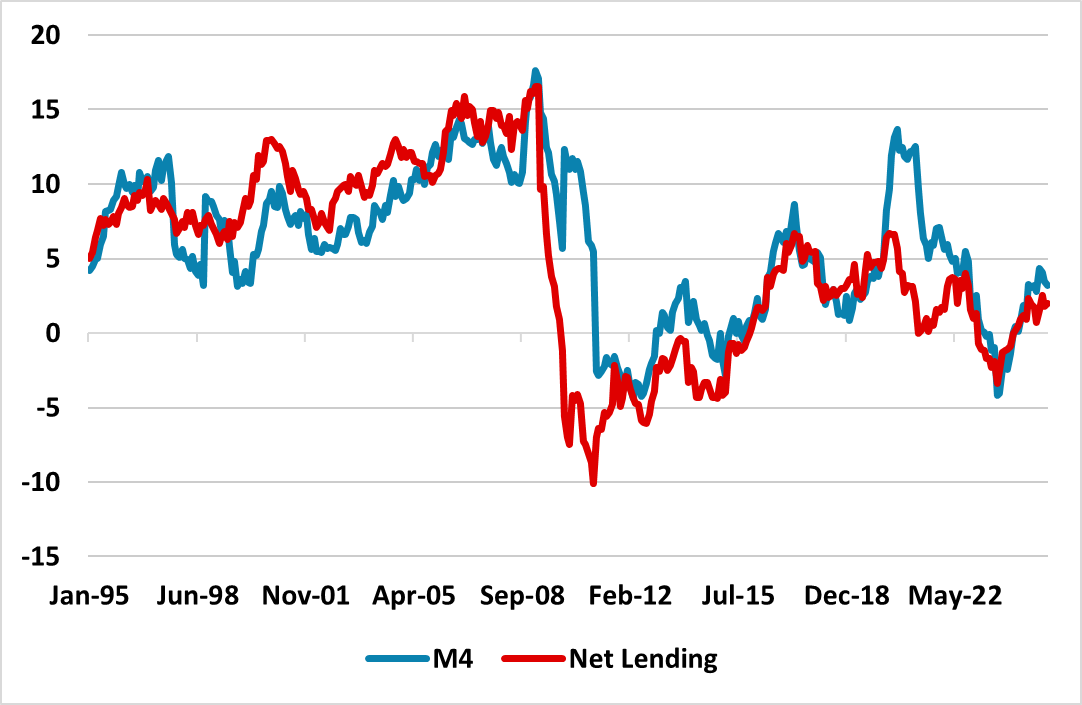

Figure 2: 10-2yr and 30-2yr Gilt Curve and Inverted BOE Policy Rate (%)

Source: Datastream/Continuum Economics.

Secondly, UK households have seen a large shift in recent decades from variable rate mortgages to 2 and 5yr fixed rate mortgages. This means the steepness of the UK yield curve is more important in impacting lending growth and GDP growth. The recent UK yield curve steepening is consistent with an easing cycle (Figure 2), but has been more noticeable for 30-2yr. The steeper yield curve in the post GFC period is not a guide, as it was accompanied by a 0.25% BOE bank rate. The 1999-06 period is probably more relevant and the steepness of the curve is approaching those peaks. This reduces the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission, which the MPC should be talking about more.

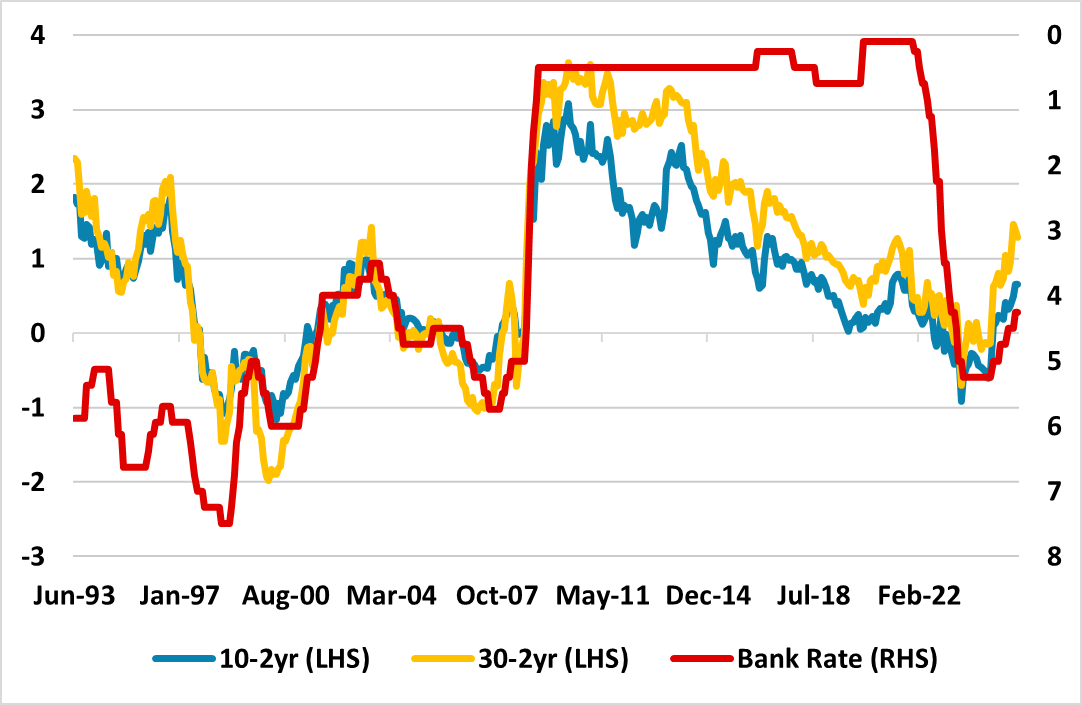

Thirdly, BOE £100 bln per annum rundown of bond holdings via QT is aggressive at 3.3% of GDP. Notably, around half of this £100 bln is outright sales rather than non-reinvestments, making the BoE the only major central bank making such sales. Combined with DMO net issuance due to the government budget deficit, this means that the private sector needs to absorb close to 8% of GDP of government bonds per annum (Figure 2). In the early days of QT, the private sector was keen to increase holdings of short-dated gilts, but as time goes on the new purchases could slow as private sector institutions reach their optimal stock holdings. This could mean that persistent QT combined with a moderately large budget deficit in 2025-26 causes the market to demand an extra yield premium. This is part of the story of 30yr gilts being at a healthy premium to 2yr gilts.

The BOE’s previous position from 2021 that QT can operate in the background is now starting to be questioned, with BOE Mann raising questions whether QT is causing tighter conditions at the long-end (here) and a BOE model simulation showing that a shock that causes a BOE rate cut but also a steeper yield curve may be contractionary (here). The primary argument for slowing is that QT is impacting the monetary transmission mechanism by delivering a steeper yield curve than normal. Most BOE speakers still seem comfortable that new repo facilities should avoid money market problems like those in the U.S. in 2019, when Fed QT reduced excess reserves too quickly. The BOE has argued that the gilt portfolio can be rundown to be partially replaced by repos to ensure that the supply of reserves is sufficient to meet the estimated range for minimum demand for reserves of between £385 billion and £540 billion. However, some MPC members could feel that this a secondary argument to slow the pace of gilt rundown to allow a slower approach to this minimum demand for reserves.

Figure 3: Change in Private Sector Gilt Holdings/GDP (%)

Source: OBR/DMO

The MPC is unlikely to want to get into a debate on whether to pencil in extra BOE bank rate cuts to offset QT and so the pressure is growing for the MPC to slow the pace of QT from £100bln pa. The latest BOE market participants survey has a median of £75bln (here) for the year starting in September. Given the weak M4 and net lending it could be argued that the BOE should be more aggressive than this, as the private sector would still need to absorb net issuance and BOE QT close to 7% of GDP that will keep conditions tight at the long-end. However, the divergence within the MPC on the bank rate will likely spillover to mean a consensus decision in September of a slowing to £75bln for the next 12 months. The BOE is also unlikely to put weights on arguments that less QT would help the government financing, given the importance on BOE independence.