Western Europe Outlook: Gradualism vs Reality

· In the UK, while headline GDP numbers look firmer, the real economy backdrop and outlook remains no better than mixed. This should improve a disinflation process driven mainly by friendlier supply conditions. The BoE will likely ease in Q4 and continue doing so through 2025 (we look for 125bps) and maybe beyond.

· As for Sweden, we have made minimal revisions to both the GDP and CPI outlook reflecting a still soft underlying picture. As a result, the economy is still fragile despite the shift in Riksbank thinking embracing faster easing.

· Inflation in Switzerland continues to undershoot target and clearly so, with our little-changed but still below-par Swiss GDP outlook unlikely to change the inflation picture. The SNB is now likely to ease into 2025.

· In Norway, having pared back its GDP growth forecasts to match our own (unchanged) outlook this year and next, and with adjusted monthly data showing a clear disinflation trend, we remain puzzled by the Norges Bank’s resistance to easing policy. We, however, now see faster moves into 2025 starting early in the new year.

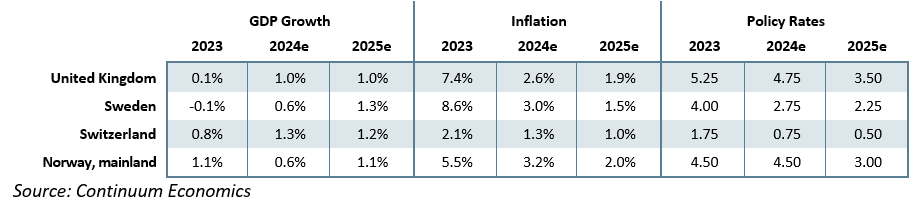

Forecast changes: Compared to our June Outlook, GDP growth forecasts have in some cases (again) been raised for this year but with larger downgrades for 2025. There is generally lower inflation forecast which still suggest a durable return to (or below) central bank inflation targets into next year. Our policy outlook is little changed out to 2025, showing slightly deeper cuts from the SNB and Riksbank and deferred easing by the BoE and Norges Bank!

Our Forecasts

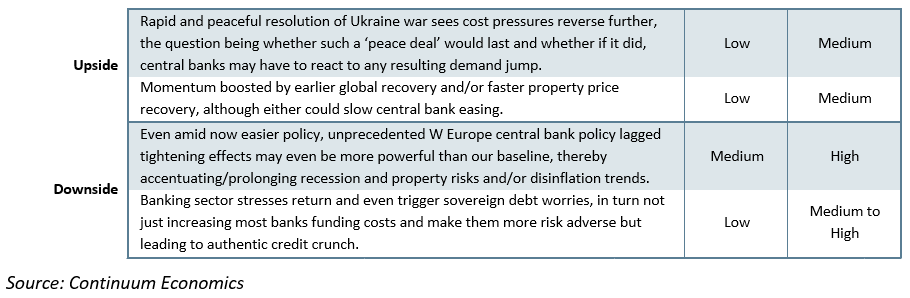

Risks to Our Views

Getting Less Gradual?

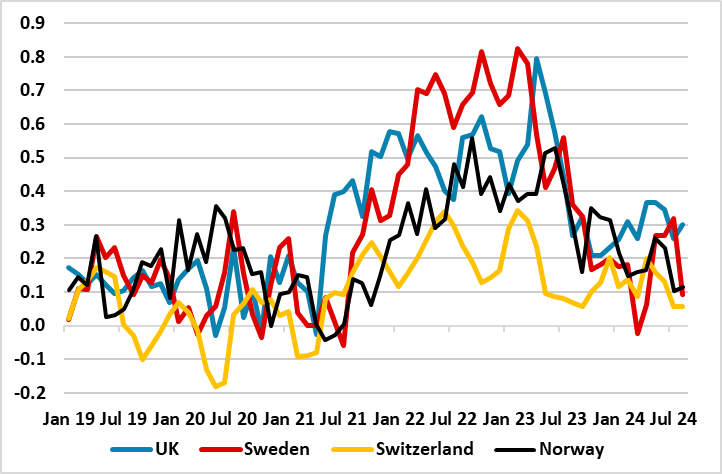

There is a clear and seemingly increasing divergence among the West European central banks about policy, most notably in regard to the start and speed of monetary easing. This is in spite of what have been clearly softer core inflation measures, particularly on a more up-to- date basis than lagging y/y rates (Figure 1). Most striking is the Riksbank. From the Board’s perspective, by initiating easing relatively early in May, it was then both reacting to weak data (both real and price wise), but more notably in giving itself flexibility to pursue what it then thought needed to be a gradualist approach to further easing. That now has changed and increasingly radically with policy put into a faster gear to front-load. The question is whether this marked shift in thinking by the Riksbank may be a foretaste for its neighboring central banks to follow. This does not apply to the SNB of course, which led the way in March and has continued at steady pace. But even that involved what was a subtle change of thinking from the SNB whose initial move was not flagged and surprised many, not least as it came in advance of, rather than following, an ECB move.

Instead, the SNB rationale change reflected a marked downward revision to its inflation outlook, in which a larger and persistent undershoot of its target was and still is envisaged. And it may be that the Norges Bank has undergone a change in thinking; previously steadfast that policy needed to be kept on hold for some time, it now suggests the first move may come in the New Year. This leaves the door open for a move at its first 2025 meeting in January, even though its formal policy projections suggest nothing until late Q1. Given that the Norges Bank is still officially projecting persistently above target inflation this change in thinking does make it seem that it felt it was getting behind other DM central banks. Which leaves the BoE; it has more formally signaled it will ease further but only gradually, many interpreting this to mean at each if the quarterly Monetary Policy Report meetings ahead. But the BoE has over-estimated inflation even in the recent past and may be doing so at present, not least against the shadow cast by weaker global growth signs. Indeed, we think the BoE will ease faster next year that it has been hinting.

Figure 1: Disinflation Continuing - Short-Run Core CPI Clearly Falling?

Source: CE-computed seasonally adjusted core m/m measures, 3-mth mov avg

UK: Conflicting Messages?

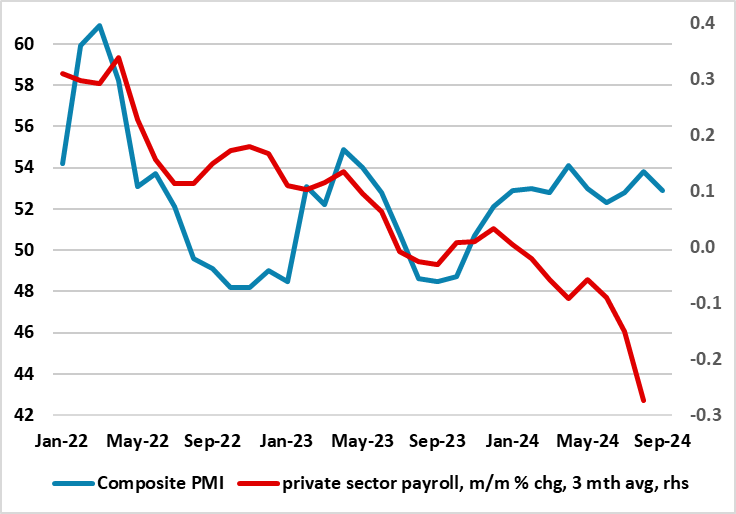

Assessing the UK outlook at the current juncture is all the more difficult given uncertainties over how much the looming (Oct 30) Budget will add to fiscal headwinds but mainly by the conflicting messages in recent data. Notably, GDP data in Q2 surprised on the upside (+0.6% q/q) for the second successive quarter, this largely explaining the 0.5 ppt upgrade we have made to the 2024 forecast. But we have stuck to our below-consensus 1.0% view for 2025 for a variety of reasons. H1 GDP numbers this year were heavily affected by swings in inter-related imports and inventories, some of which were related to volatile monetary gold holdings - a further recovery in imports may weigh on GDP into next year. Actual GDP momentum may also be overstated by the official Q2 headline reading as monthly numbers have shown just one rise in the last four sets of data. Moreover, while business survey data have started to soften, they may still be telling an over-optimistic message for coming months as the UK PMI numbers conflict with much more downbeat official data on both manufacturing and private sector payrolls (Figure 2) as well as showing a puzzling divergence from notably weak(er) EZ business survey numbers.

However, the main concern remains the impact of the sizeable tightening in monetary policy that has hardly been reversed and has caused tighter financial conditions not only in terms of higher debt servicing but also increasingly in much higher rents. Indeed, policy is still biting the economy through the credit channel, this very much highlighted by (admittedly diminished) weakness in bank credit and deposits, but where real growth in both is still negative.

Moreover, momentum of late has been partly dependent upon non-cyclical parts of the economy, in particular public services, which are likely to come under pressure from spending restraint even before the medium term. Some clarification may come after the Budget but this is also likely to see further tax rises over and beyond already planned income tax threshold freezes and may thus not only possibly accentuate already planned sizeable fiscal tightening ahead, but may concentrate it even more into the next 1-2 years. In support of her high-profile pro-growth agenda, the Chancellor will hope that her deregulation plans, the so-called National Wealth Fund manifesto initiative and more pro-EU relationships will persuade the OBR not to pare back what are already optimistic GDP growth assumptions that assume an average rate nearly 2% in the next four fiscal years. In this regard there may be some tweaking of the fiscal rules, which may provide the Chancellor with some more budgetary leeway.

This below-par growth outlook, should add to the disinflation signs seen of late which we suggest have been more a result of an easing in supply pressures Indeed, even amid hints that UK potential growth may have fallen towards just 1%, excess supply is likely to open up into next year and may be even as much as 1% of GDP in 2026. Thus, it is no surprise that CPI headline has fallen back to target and though energy swings may cause it to rise a little further into next quarter, it will then fall afresh and we still see it averaging below target in 2025.

Figure 2: UK Activity Messages – Diverging?

Source: ONS, Markit

Admittedly, there are still some apparently less ambiguous brighter signs regarding housing. However, the level of transactions is still low, this being the main factor that will affect and weigh on households, through the year to a degree that very much risk the 0.2% consumer spending rise in 2023 being exceeded much this year and with not much better on the cards for 2025. But an upside risk is that if the election has delivered what looks like to be strong and stable administration, an ensuing reduction in political uncertainty may bolster confidence more significantly, particularly for businesses.

As for the BoE, the expected unchanged MPC decision this month came with what some may regard was a lack of any major dissent. But that 8:1 vote is very much a reaction to the closeness of the MPC vote last month to cut Bank Rate by 25 bp to 5.0%. It is also a preference from the MPC majority to pursue gradual easing, this laid out more formally this time around suggesting overtly that ‘a gradual approach to removing policy restraint remains appropriate’. This slightly more explicit policy guidance also reflects moderate differences within the MPC principally over how quickly current restrictive policy stance will temper underlying domestic inflationary pressures. Clearly, a further cut is on the cards for the November meeting which will have fresh forecasts which should reiterate the inflation undershoot projected in August and include the repercussions of the Oct 30 Budget. But that may now be the only further move this year but with over 100 bp of easing projected in 2025 when the MPC may be forced to be a little less ‘gradual’.

Sweden: Riksbank into Faster Reverse Gear

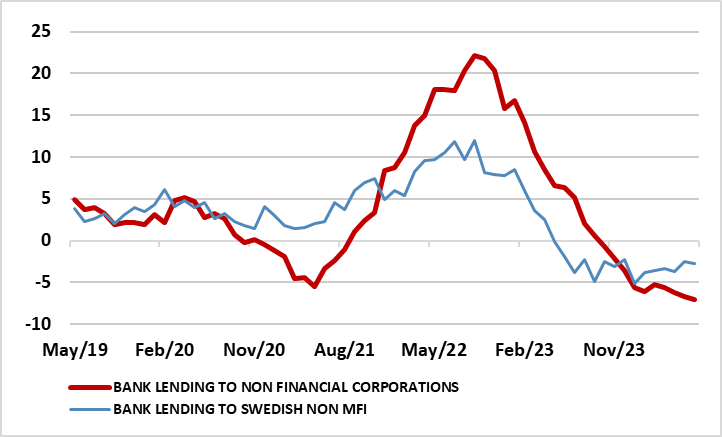

The omens for Swedish real activity should be getting better given now emerging easier monetary and fiscal policy stances. It is clear that the Riksbank is cutting rates somewhat faster than it initially planned, now including some front-loading. This is all the more notable given that Sweden (unlike most other DM economies) is much more sensitive to changes in Riksbank rates given that the mortgage market is dominated by flexible rates not fixed. Moreover, the recent State Budget saw a clear fiscal loosening involving measures worth some 1.3% of GDP that will see the budget gap more than triple to around 2% of GDP this year and fall only slightly next – the debt to GDP ratio may rise but only toward a still very low 34% next year. However, these factors (while posting some upside risks) have to be put aside the weaker growth signs in W Europe generally as well as by the fact that Riksbank tightening still seems to be biting and clearly so given the continue marked and nominal fall in bank lending (Figure 3) and deposits. Indeed, we think that weak bank lending is a reflection of Riksbank policy also biting unconventionally as its balance sheet reduction has caused a marked drop in bank deposits of almost 4% in the last two years and where this weakness is affecting banks willingness/ability to lend.

As a result, we have adhered to our below-consensus GDP outlook still seeing a 0.6% rise this year and actually pared back the 2025 picture to 1.3%. Indeed, the most recent signs suggest downside risks, not least to consumer sending which this year may hardly repair the 0.3% fall of last year and where any firmer tone for 2025 will (in terms of GDP) be offset by a belated recovery in imports. This may mean that the current account surplus drops back below 6% of GDP this year and maybe further into 2025.

The consumer picture is made more uncertain by an emerging rise in unemployment with the rate moving decisively back above 8% in 2024 and then staying there in 2025. This should mean that wage growth this and next year may fall from last year’s 3.8%. As telling is the likelihood that housing construction (which has already fallen steeply due to lower house prices, higher construction costs and more expensive financing) continues to contract in to next year. While we see a gradual recovery emerge from late this year leading to an output gap of over 1% through into 2025.

This is only likely to reinforce the prices situation where more signs of disinflation continue to amass, and broadly so. Indeed, targeted inflation (CPI-ATE) has fallen below the 2% goal. But this disinflation has been very evident in seasonally adjusted m/m core CPI readings, very much hinting that ex-energy (core) inflation has been undershooting target for some time and earlier than that circa-Q1 2026 forecast the Riksbank has just been forced to revise. Notably, this includes clear signs of slowing services inflation. This drop has persuaded us to revise down our 2025 CPI projection by 0.1 ppt this year to 1.5%, a picture that is now being acknowledged: inflation expectations two and five year measures are back at, or just below, pre-pandemic averages

Figure 3: Bank Lending Still (Very) Negative

Source: Riksbank, % chg y/y

A third successive 25 bp rate cut (to 3.25%) surprised no-one at the latest Riksbank meeting. More notably, updated forecasts more formally validated both the likelihood and the rationale for the two added cuts by end-year that the Board hinted previously and which largely are in line with the alternative (downside) policy scenario it had offered previously. Regardless, it is clear that while lower inflation has provided the scope to ease policy in this speedier manner, the rationale is increasingly that from a weak economy. The latter is highlighted by a marked downgrade to the Riksbank’s’ 2024 GDP picture, only partly offset by small upgrade to an above trend and what we think is an optimistic 1.9% 2025 (solely a result of the faster easing in its monetary stance being signaled). Notably, the Riksbank now points to additional easing some 25 bp lower than the circa-2.5% terminal rate its previous projections suggest may be the case., thereby now in line with our long-standing forecast. However, even the Riksbank now points a risk scenario in which the policy rate falls below 2%.

Switzerland: SNB Seeing Larger Inflation Undershoot

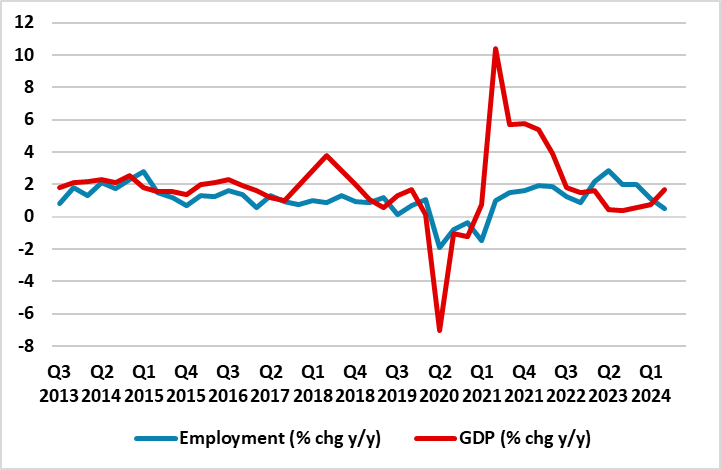

GDP numbers so far this year have been more than solid, but have been boosted by sports events effects and unseasonable good weather. Thus, rather than being indicative of above trend growth, the economy is actually showing a below-par performance, but not markedly. Even so, these factors explain the small upward revision to the 2024 growth picture compared to three months ago. But the 2025 outlook is intact, still consistent with a slightly below trend-type outcome of 1.2%. All of which would suggest that downside risks have lessened. But this ignores the emerging weakening in the Eurozone, and particularly Germany, which is likely to mean that the Q2 surge in Swiss manufacturing (20% of GDP) is unlikely to persist, not least as pharmaceutical demand continues to normalize and construction is likely to remain fragile into 2025. But there are also more domestic risks which range from possible property and financial market corrections to the transmission of monetary policy turning out to be stronger than currently assumed, even amid the clear policy easing now underway. Indeed, some risks may be materializing in the form of weaker labor market signs (Figure 4) which suggest consumer spending is now likely to grow slower than GDP but still enough to fuel import growth that matches that of exports. Indeed, into 2025, this may help keep the current account surplus above the 7.0% of GDP outcome seen in 2023. But there is also weak capex where some recovery from this year’s likely fall may occur, the former a result of low industrial capacity utilization and weak order books.

Import trends are also helping weigh on prices. Indeed, we have pared back our CPI forecasts for this year by a notch to 1.3%, and be even more to the 1.0% we now see for 2025. This continues to reflect still limited wage pressures and unusual mix of services in the CPI basket. Indeed, recent actual inflation dynamics certainly suggest disinflation continues. This below-target current backdrop largely reflects the impact of the previously strong currency, but we also discern some signs that domestic price pressures have continued to fall. In turn domestic prices have helped moderate core inflation, both to rates well below those consistent with the SNB inflation target, especially in adjusted m/m terms.

As a result, we largely echo the SNB’s updated inflation forecast even more clearly pointing to a below-target picture in the latter part of its forecast horizon even after the third successive rate cut it delivered in September. Even so, rate policy is still biting but somewhat less discernibly, not least given the emerging recovery in private credit growth which at, back over 2% y/y, up from the lowest since 2016. The credit slowdown is also still demand driven, reflecting the clear softening in property prices (most particularly for apartments) which will probably extend through the coming year, in line with SNB wariness of such risks.

Figure 4: Employment Growth Waning

Source: SECO, Federal Statistical Office

As for the policy outlook, very much as expected, the SNB has just repeated the 25 bp policy rate cut that it had made twice since March. This took the policy rate to 1.0% and reflected an even clearer below-target inflation picture in both recent actual numbers and the updated outlook. This flagged further easing ahead. Indeed, the SNB was quite open about this suggesting that ‘Further cuts in the SNB policy rate may become necessary in the coming quarters’. Perhaps somewhat excessively, much of this inflation weakness is attributed to the strong Swiss Franc. But we stress that domestic inflation is also softening too, especially in regard to seasonally adjusted m/m numbers which show that such price pressures are falling in line with core inflation albeit not to a degree that warrant the inflation undershoot seen by the SNB. Notably, this much weaker SNB inflation outlook comes even with solid and near-trend GDP growth of around 1% this year and 1.5% expected next year. Even though we think the SNB inflation picture is probably too low, another same sized move in December looms and now with it likely that a policy rate trough of 0.5% will arrive in Q1.

Norway: Stubborn Norges Bank

Having pared back its GDP growth forecasts to match our own outlook this year and next, and with adjusted monthly data showing clear disinflation, we remain puzzled by the Norges Bank’s resistance to easing policy, though it is now signaling rate cuts in the New Year. Indeed, actual mainland GDP data for H1 suggest possible downside risks to the 0.6% we see for this year, not least with early signs for the current quarter (eg car sales) showing marked weakness. And with weaker signs emerging elsewhere in W Europe, there may be downside risks to out 2025 projection of 1.1%, this reduced by 0.2 ppt from three months ago. Furthermore, construction is still contracting with the ensuing drop in properties for sale possibly explaining the recent recovery in house prices. That latter recovery, alongside wage gains of around 5% (that may extend into 2025), has boosted real household incomes, but this has yet to see consumers more willing to spend. All in all, the economy is still feeling the pinch of both lagged monetary tightening and weak growth elsewhere in W Europe and beyond, the former highlighted by a continued drop in real private sector credit growth.

This view very much reflects 2024 seeing a second successive year of negative fixed investment, and one that extends beyond weak construction. But in contrast to optimistic Norges Bank thinking on household spending, after a clear fall in consumer spending last year, we do not see any recovery in 2024 and only modest growth next year. This is especially as the recent rise in house prices is fragile and unemployment is starting to rise. This is likely to add to the fall in inflation now very much unfolding, with the CPI-ATE measure continuing to undershoot Norges Bank projections, and where adjusted m/m CPI data imply currently below-target price pressures. As a result, we have revised lower the anticipated average rate for CPI inflation this year to 3.2%. This also encompasses the headline rate hitting 2% by H1 next year and then remaining there through 2025 as productivity and lower profit margins offset wage pressures. This is hardly surprising as the next two years should see an output gap emerging and persisting.

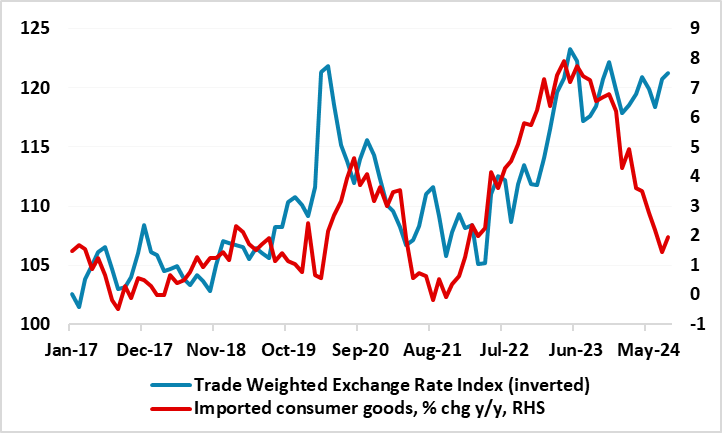

Figure 5: Weak Currency Has Not Stopped Imported Inflation From Tumbling

Source: Stats Norway

As with the five previous policy meetings, the Norges Bank kept its policy rate at 4.5% earlier this month and equally unsurprising moderated its previous hawkish rhetoric – now suggesting that ‘the time to ease monetary policy is approaching’. The scheduled decision on Jan 23 looks set to see the first rate cut, although this is not fully consistent with the little-revised official policy outlook, which indicates a slightly faster decline through 2025. The Bank sees policy risks still seem balanced, despite its pared-back mainland real economy outlook and what have been broadly softer than (Norges Bank) expectations for CPI data of late, and where underling price dynamics are very weak. Even so, amid this slight change in its rhetoric, the (weak) krone is still at the center of its thinking. This to us seems very puzzling as a) this hawkish policy leaning has failed to bolster the currency since Rates peaked last December and b) the weak currency has not prevented a marked fall in inflation encompassing much reduced imported price pressures (Figure 5). While the easing we envisaged for this year now looks unlikely, we now see some 150 bp of rate cuts in 2025, ie 50 bp more than the Norges Banks is advertising!