UK Fiscal Update: Bring Out Your Debt

Having stressed that an (urgent) assessment of the fiscal backdrop will be presented to parliament before the summer recess, Chancellor Reeves made her statement today. In line with much-flagged media reports, she said there is a circa- £22bn ‘black’ hole in the fiscal arithmetic. Without being specific over the exact timeframe this hole applies to - it appears to be a possible overrun of current spending targets but we also assume it equates with the fiscal leeway estimated by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) needed to meet the fiscal goal of government debt falling by the final year in a five-year rolling schedule. But the likely fiscal consolidation could at the margin tip the BoE into a rate cut sooner rather than later while the promise of fiscal rectitude will please the gilt market not least as it may add to disinflation pressures, although alternative fiscal goals should be considered.

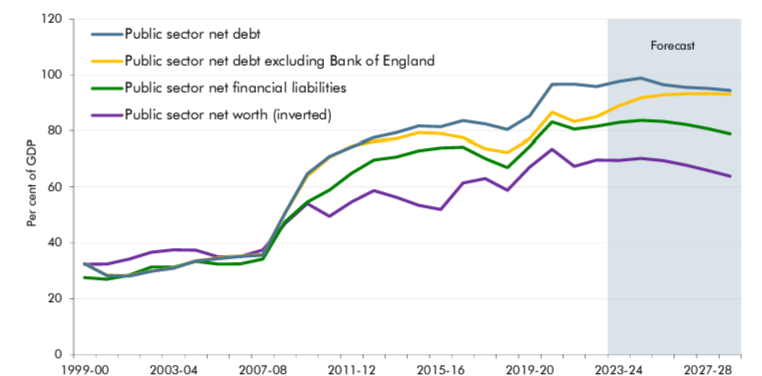

Figure 1: Alternative and More Forgiving Government Fiscal Goal Measures.

Source; March OBR – four measures of the public sector balance sheet

The Devil in the Details

More will be learned with the Budget she announced for October 30, which will also see a much needed Spending Review that will conclude next spring and will detail departmental expenditure beyond the current fiscal year, ie for three FY. Today’s statement is very much a political event, and to put blame on others for the difficult policy decisions due in coming months. Nonetheless, markets may like the manner fiscal prudence is being prioritized. But clearly, this a softening up exercise for more tax rises and spending cuts to be detailed in the Budget. They already include diluting and delaying capital spending plans, including roads and hospitals, especially those that the Chancellor suggested are ‘unfunded and on unfeasible timescales’. As for taxes, with Labour having excluded raising rates of income tax, national insurance, VAT or corporation tax, the list of options is heavily circumscribed, not least as the tax areas ruled out cover some 75% of total government receipts.

Downside, not Upside Risks to Growth?

One question that needs addressing is how this fiscal consolidation will affect the real economy outlook not least as this statement points to £5.5 bn of savings this year and £8.1 bn next year (0.3% of GDP alone). The Chancellor will hope that her deregulation plans; the so-called National Wealth Fund manifesto initiative and more pro-EU relationships will persuade the OBR not to pare back what are already optimistic GDP growth assumptions that assume an average rate nearly 2% in the next for fiscal years. If not, then the black hole may much larger than £20 bn. NB: Our current estimate is a black hole of some £13 bn, but this is largely due to weaker GDP assumptions.

As for how that £22 bn is derived relative to the existing £13 bn estimated by the OBR is unclear even given the documentation offered by the Chancellor. Some £ 6 bn probably reflects scheduled fuel duty increases which would be both unpopular and inflationary. Some reflects meeting pay reviews for public workers. It may also reflect recent monthly fiscal data which show government borrowing in the first three months of 2024-25 some £3.2 bn above OBR projections mainly due to consumption expenditure being £4.6 bn higher than forecast. But the big question is whether source of the rest if the hole is cyclical or structural, with the latter looking both more likely and more serious.

Alternative Fiscal Barometers

All of which brings up the question of whether covering the black hole would be the result of excessive attention to one particular fiscal rule based around on particular measure of government debt. As Figure 1 shows, and based on the OBR’s own assessments, there are other possibly more sensible measures as they encompass government assets as well as debt and are thus wider measures of the government’s balance sheet.

Indeed, OBR forecasts for public sector net financial liabilities (PSNFL) and public sector net worth (PSNW), show that (as % GDP) they both peak in 2024-25 and then fall through the forecast horizon, unlike the existing debt measure (Net debt ex BoE) which only just starts to fall five years hence. Not only would these unleash much more fiscal ‘space’. This is because the current debt measure rises by 4.2 ppt of GDP between 2023-24 and 2028-29, while PSNFL falls by 4.2 ppt of GDP. This reflects the cost of acquiring assets such as student loans which add to debt, whereas both the assets and liabilities are recorded in PSNFL so largely net off. (Inverted) PSNW falls faster still, by 5.6 ppt of GDP over the forecast. This could increase fiscal leeway by over £ 200 bln potentially and would not be a shift in fiscal goals that would perturb the gilt market, albeit it may have some impact on BoE thinking depending how and if such leeway is used.