Western Europe Outlook: Easing Cycles Diverge?

· · In the UK, while downside economic risks may have dissipated, the real economy backdrop and outlook is still no better than mixed. This should accentuate a disinflation process hitherto driven mainly by friendlier supply conditions. The BoE will likely ease in Q3 and continue doing so through 2025 and maybe beyond.

· As for Sweden, while we have made clear revisions to both the GDP and CPI outlook, we do not think this reflects major changes to the underlying picture. As a result, the economy is still fragile with the partly-resulting disinflation repercussions still shaping Riksbank thinking.

· Ironically, even amid a more resilient economy than its neighbors, inflation in Switzerland continues to undershoot target and clearly so, with our little-changed but still below-par Swiss GDP outlook coming alongside further downgrades to the inflation outlook that suggest more sizeable easing looks likely this year.

· In Norway, even amid it having seen inflation undershoot its expectation, and where any recovery is still fragile, the Norges Bank is paying more attention to wage-related risks. This is to a degree where it has deferred any easing until 2025. We, however, see faster and larger moves into 2025 starting in Q4 this year.

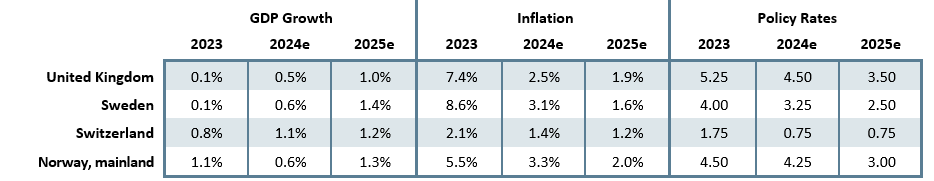

Forecast changes: Compared to our March Outlook, GDP growth forecasts have (again) been raised for this year but with minimal revisions for 2025. There is similar story regarding inflation, but where these still suggest a durable return to central bank inflation targets into next year, if not even more below for the SNB. Our policy outlook is little changed, showing slightly deeper cuts from the SNB but deferred easing by the BoE and Norges Bank!

Our Forecasts

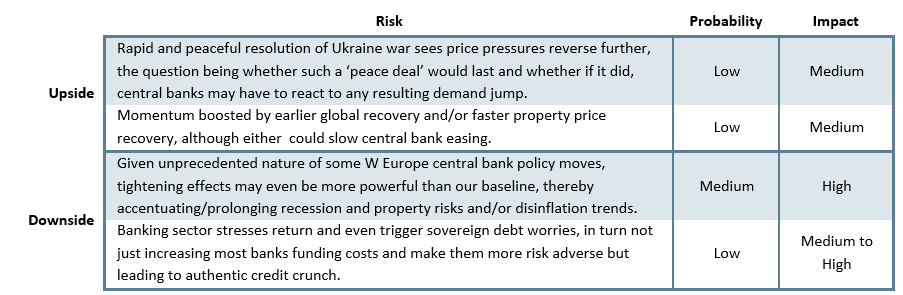

Risks to Our Views

Some Divergence

In recent Outlooks we have highlighted the extent to which common cross currents had become more evident across Western Europe’s economies. To some degree that continues given that all are reporting some recovery in residential property prices, albeit where, in Switzerland, this has not persuaded the SNB that vulnerabilities in the sector have ended. This recovery is notable (but perhaps fragile) as we would contend that the impact of interest rate hikes has yet to fully filter through. Indeed, policy hiking has effectively having added to, if not replaced, energy as the concern for beleaguered consumers and companies, even with all of the governments involved well into the process of unwinding energy support measures. Indeed, the rate hike impact is still clear in the manner in which all four countries have seen private sector credit slow, if not contract, especially in real terms. To us, this is partly being driven by central bank balance sheet reductions, although, even in Norway where the latter has not been occurring, real credit growth is also negative.

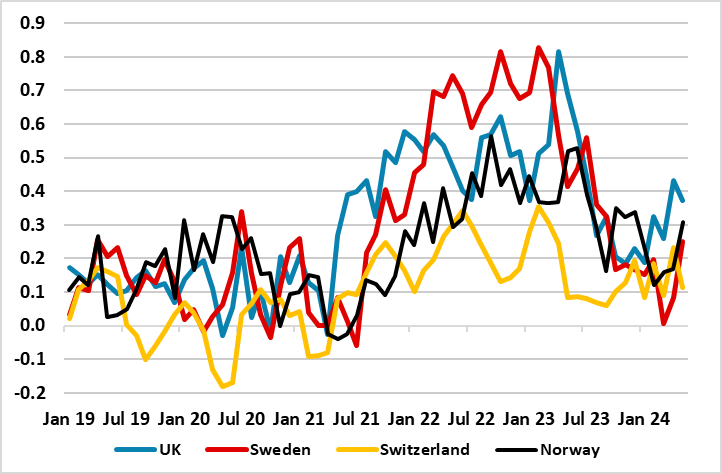

A further still-common theme is actual underlying disinflation, this occurring against similar modest and fragile economic recoveries. This disinflation is very much evident in Figure 1, where the seasonally adjusted core CPI measures we have computed (and flagged in recent Outlooks) are largely now consistent with those targets having already been met. Admittedly, there has been some pick-up in the last month or so, which we think is more noise than fresh trend, very much concentrated on domestic services which makes the correlation across the countries somewhat puzzling.

This brings up to what we would regard as emerging divergence, this occurring in regard to monetary policy, at least in action terms. All four respective central banks some time ago flagged a peak in conventional hiking and even pointed explicitly to easing. But in spite of the similar inflation backdrops, Switzerland and then Sweden have exercised their respective easing biases, the UK is seemingly actively considering doing so, while the Norges Bank has backed off, deferring cuts it originally considered may occur in the next few months to early next year. This very much highlights what may be different and thus diverging reaction functions of these central banks.

Regardless, perhaps one final and possibly common remaining theme that we identify based on what we still think are the downside activity risks we see through 2024 is that all central banks may see a real economy backdrop into 2025 that surprises on the downside. The result that all four central banks will have both the scope and rationale to continue cutting well into 2025!

Figure 1: Is Disinflation Continuing - Short-Run Core CPI Still Volatile?

Source: CE-computed seasonally adjusted core m/m measures, 3-mth mov avg

UK: No Honeymoon Facing New Government?

While it is clear to that the UK economy is out of recession, we are doubtful that the strong Q1 GDP reading (which the BoE sees being repeated this quarter) is either durable or even genuine, certainly in regard to private demand. Notably, clearer softness in the labor market more chimes with the weak domestic demand picture seen in last quarter’s national accounts. Moreover, we are not sure from where the economy would be getting fresh momentum, especially as the encouraging recovery in real wages may not persist and is being offset somewhat by a demand driven narrowing of company profit margins and by threshold-driven personal tax rises out to 2026. Moreover, businesses are losing much of the energy support cushion through 2024. However, the main concern remains the impact of the sizeable tightening in monetary policy that is yet to be reversed and has caused tighter financial conditions not only in terms of higher debt servicing but also increasingly in much higher rents. Indeed, policy is biting the economy through the credit channel, this very much highlighted by (admittedly diminished) weakness in bank credit and deposits.

Thus, while there are some signs that look as if the economy is recovering, they need more perspective. Notably, GDP details suggest that any such apparent recovery has been buttressed by falling imports which have boosted headline real growth by some 1.5 ppt cumulatively in the last three quarters. This will surely reverse over the next year. In addition, and undermining the message of (admittedly more recently mixed) business surveys, momentum of late has been very much dependent upon non-cyclical parts of the economy, in particular public services, which are likely to come under pressure from spending restraint even before the medium term – some clarification after the July 4 election? Against this backdrop, after the little growth we see this quarter, momentum thereafter will only gradually take up steam and only to a degree that 1% is still what we see for GDP growth next year; the 2024 picture has been revised up after the Q1 surprise.

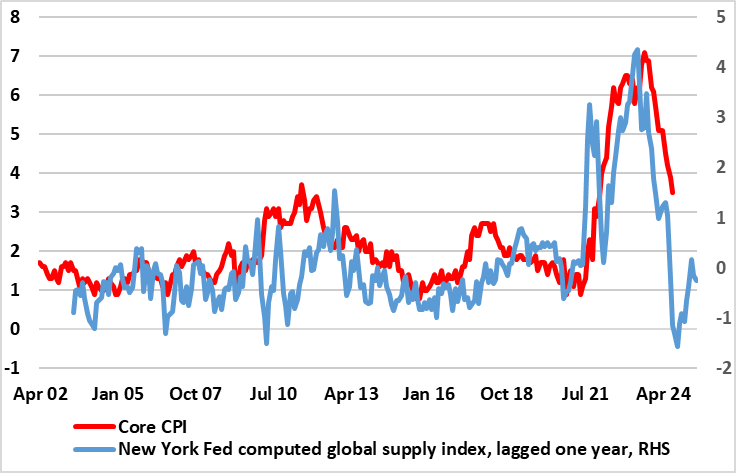

As a result, we (still) think weak activity will accentuate the fall in inflation seen of late which we suggest hitherto has been a more a result of an easing in supply pressures – actually a view that the BoE partly embraces and one backed up by data suggesting easier global supply pressures (Figure 2). Indeed, even amid hints that UK potential growth may have fallen towards just 1%, excess supply is likely to open up into next year and may be even as much as 1% of GDP in 2026. Thus, it is no surprise that CPI headline has fallen back to target and though energy swings may cause it to rise a little in H2 it will then fall afresh and we still see it averaging below target in 2025.

Figure 2: UK Disinflation – So Far, Supply Driven?

Source: ONS, New York Fed Global Supply Chain Pressure Index

Admittedly, there are some brighter signs regarding housing. But the level of transactions is still low, this being the main factor that will affect and weigh on consumer spending, through the year to a degree that very much risk the 0.2% rise in 2023 being exceeded this year. Another imponderable, against the political issue of immigration, made all the more high-profile by election campaign, the question remains how growth ahead may be dependent non workers from abroad, something that also has clear fiscal reverberations. But it also has to be noted as an upside risks is that if the election delivers what looks like to be strong and stable administration, the ensuing reduction in uncertainty may bolster confidence more significantly, particularly for businesses.

As suggested above, the fiscal side is hardly going to be supportive not least as the fragile recovery keeps public borrowing nearer 4% of GDP out past 2025, this in turn pulling the debt ratio (now over 91%) higher still, all being issues glossed over at least politicians in the campaign. The likely incoming Labour government is stressing it will continue a broad fiscal consolidation but, if so, it faces some unpleasant decisions in the course of the next few months.

This continued consumer weakness (highlighted by still very subdued survey readings regarding any willingness to spend) has helped curtail imports, while Brexit related distortions (despite Labour seeking better relations with the EU) and a slower global economy will weigh on exports. As a result, the likely less-negative current account deficit of last year (down to around 3% of GDP) may not improve further in either 2024 or 2025.

As for the BoE, Bank Rate was kept at 5.25% for the seventh successive MPC meeting this month, with its rhetoric largely unchanged. But there were clear hints that policy easing is under much more active consideration (here). While there were still only two formal dissents, the minutes clearly suggested that for some of the remaining seven members, the policy decision was finely balanced. This implies this group (which may be as large a four) could swing to an actual cut in August not least as updated forecasts due then may add to the disinflation ‘story’ with a further forecasts of inflation below target at the end of the 2-3 year projection horizon. The important thing is that even with a few cuts in the next six months, policy would still be clearly restrictive and the MPC has to consider ‘for how long Bank Rate should be maintained at its current level’. Notably, if rates are cut in August that would mean a turnaround from peak to easing of 12 months, somewhat above the average seen in previous cycle of around eight. Regardless, we see up to three 25 bp cuts this year and around four such moves next year, this still hardly taking policy to neutral.

Sweden: Riksbank Easing Underway, More to Come

While we have made clear revisions to both the GDP and CPI outlook, we do not think this reflects major changes to the underlying picture. This year’s GDP outlook has been upgraded from a slight fall to a rise of 0.6%, this a result of the surprise strong Q1 GDP reading and sizeable revisions to back data. But nearly all of the 0.7% q/q rise was inventory based and we think this will partly unwind this quarter and possibly through H2, with the further fall in consumer spending possibly more indicative of the continued fragility of the real economy, impaired by the emerging rise in unemployment with the rate moving decisively back above 8% in 2024. This should mean that wage growth this and next year may fall from last year’s 3.8%. As telling is the likelihood that housing construction (which has already fallen steeply due to lower house prices, higher construction costs and more expensive financing) continuing to contract this year. Even so, there may be some support from what may be a slight recovery in house prices. Overall, we have pared back the 2025 growth picture by a notch to 1.4%, a slightly below trend-type outcome even on the back of a largely unchanged q/q profile that sees a gradual recovery emerge from Q3 this year but where an output gap of over 1% is likely to appear through 2024. Indeed, survey data still suggests below par activity in the immediate future.

Admittedly, there may be some emerging upside risk to this outlook, albeit mainly for next year due to a possible fiscal boost. Indeed, an expansive stimulus package may be on the cards in the looming autumn budget as the relatively unpopular government coalition, realizing it is entering the latter half of its term (ahead of a scheduled 2026 general election) uses the ample fiscal room provided by both low current borrowing and debt totals while still be consistent with current fiscal rules. In particular, this may address clear infrastructure shortcomings in the economy and mean that a budget gap of around 1% of GDP may continue into 2025 but still mean that the debt ratio stays round 31%. But this year, consumer spending may start to recover, but grow no faster than overall GDP, with exports sturdy but held back by softness elsewhere in Europe and where net trade may be negative as imports into 2025 repair the drop seen through last year. This may mean that the current account surplus drops back below 6% of GDP this year and maybe further into 2025.

This is unlikely to affect the prices situation where more signs of disinflation continue to amass, despite a pick-up in the May CPI data which was probably an aberration due to the short-lived impact on services prices from a few one-off special entertainment events. This is very evident in seasonally adjusted m/m core CPI readings (Figure 1) which have showed a much softer profile prior to May, very much hinting that ex-energy (core) inflation undershoots target earlier than that circa-Q1 2026 forecast by the Riksbank. Indeed, we think CPIF inflation (the actual targeted measure) may drop below target in coming months. This drop has persuaded us to revise down our 2025 CPI projection by 0.2 ppt this year to 1.6% even after an upgrade to the 2024 projection due to a series of aberrant factors, a picture that is now being acknowledged: inflation expectations two and five year measures are back at pre-pandemic averages (Figure 3).

But we continue to think that Riksbank policy is also biting unconventionally as its balance sheet reduction has caused a marked drop in bank deposits of over 3% in the last 20 months and where this weakness is affecting banks willingness/ability to lend and is thus accentuating demand driven weakness in credit growth. Indeed, private credit growth is still contracting clearly, chiming with the drop in bank deposits.

Figure 3: Swedish Inflation Expectations Re-Anchored?

Source: Prospera

The Riksbank has already started to make its policy stance less contractionary, at least in conventional terms, initiating an easing cycle last month by cutting the policy rate 25 bp (to 3.75%), despite clear concerns it had flagged about recent and continued krona weakness. More notably, the Board, with no sign of any internal dissent, was explicit in highlighting a near-term policy path, advertising a likely two further such cuts in H2 this year, this chiming with our own long-standing view but where those advertised moves are likely to arrive at policy verdicts scheduled on August 20 and November 7. Despite the Riksbank pointing to a further 2-3 such cuts next year, it was more coy about the longer-term outlook, noting risks from a strong US economy, weak currency and geopolitical tensions. By starting the easing process relatively early, the Board was giving itself flexibility to pursue what it thinks needs to be a gradualist approach to further easing and we still see a further 75 bp of cumulative easing through 2025 with the easing cycle probably extending in to 2026 as otherwise policy may still be somewhat restrictive.

Switzerland: SNB Eases Further and Still Sees Inflation Undershoot

Near trend-type GDP growth has become the norm of late and this may continue, albeit with recent data buoyed by unseasonable weather having boost utility production markedly. Admittedly, the latter may reverse, making current quarter GDP slow, but only from the sports-event distortion of Q1; this aberration also explaining the small upward revision to the 2024 growth picture compared to three months ago. But the 2025 outlook is intact and is now being backed up by somewhat better survey data numbers (Figure 4), which are consistent with a near trend-type outcome of 1.2%, all suggesting that downside risks have lessened. Admittedly, they have not fully dissipated with Swiss manufacturing still facing headwinds as pharmaceutical demand continue to normalize and construction is likely to remain fragile into H2. But the risks range from possible property and financial market corrections to the transmission of monetary policy turning out to be stronger than currently assumed. Additional risks include even more spill-over from weakness in Germany and also a possible energy shortage in the coming winter albeit where Switzerland is partly insulated from this given its large nuclear and hydro reliance. But even so, helped by the still solid labor market, consumer spending is likely to grow in line with GDP and also, in turn, fuel continues strong import growth that matches that of exports. Indeed, into 2025, this may help keep the current account surplus around the 7.6% of GDP outcome seen in 2023.

Import trends are also helping weigh on prices, so that even the near-trend growth seen of late and projected to continue may not stop recent disinflation – it seems that low inflation may be driving solid growth! Indeed, we have pared back our CPI forecast for both this year and next each by a notch to 1.4% and 1.2% respectively, this reflecting still limited wage pressures and unusual mix of services in the CPI basket. Indeed, recent actual inflation dynamics certainly suggest disinflation continues. Headline CPI looks set to match the 1.4% existing projection of the SNB for the current quarter. This below-target current backdrop largely reflects the impact of the hitherto strong currency, but we also discern clear(er) signs that domestic price pressures have continued to fall, with the latter helping moderate core inflation, both to rates also well below those consistent with target in adjusted m/m terms.

As a result, we understand the SNB’s updated inflation forecast even more clearly pointing to a below-target picture in the latter part of its forecast horizon even after the second successive rate cut it delivered this month. Even so, rate policy is still biting but somewhat less discernibly, not least given the emerging recovery in private credit growth which at, back over 2% y/y, up from the lowest since 2016. The credit slowdown is also still demand driven, reflecting the clear softening in property prices (most particularly for apartments) which will probably extend through the coming year, chiming with SNB wariness indicative of such risks.

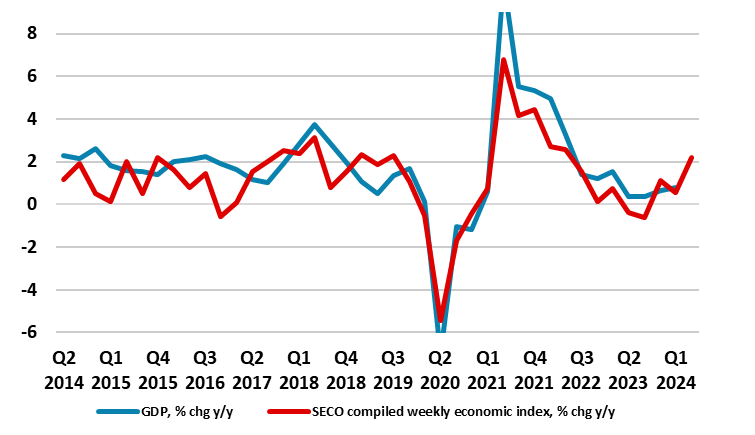

Figure 4: Swiss Activity Looking Up?

Source: SECO

As for the policy outlook, given those inflation forecasts out to 2026, this suggests that a further cut is highly likely in the September quarterly policy assessment and now also December especially if the SNB’s repeated worries about property market vulnerabilities materialize. It is noteworthy that the SNB continues to threaten further CHF sales, with the opposition to balance sheet increase now being removed by the persistent CHF strength.

Norway: Slightly Brighter

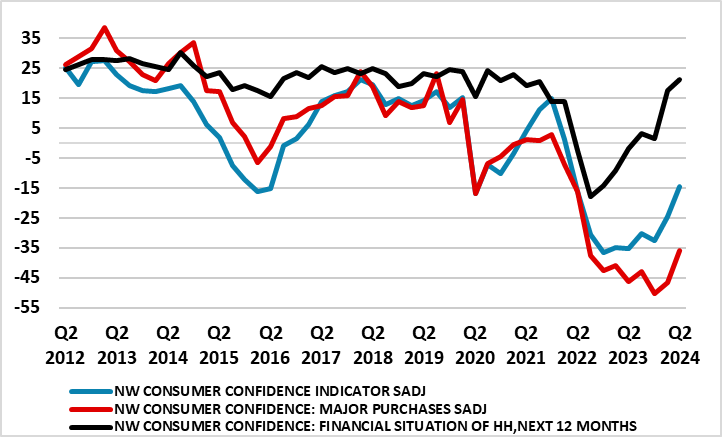

With official monthly growth data all but suspended for the time being, the backdrop, let alone the outlook, is somewhat murkier. Survey data, admittedly, are looking up, but the likes of the Norges Bank Regional numbers are hardly suggesting an imminent return to anything like trend growth while the survey’s upgraded capex picture for 2025 looks odd amid results still pointing to below par capacity utilization and a central bank that has hinted no early cut to interest rates. Moreover, the small GDP gain in Q1 may be reversed this quarter as the former may have been more a result of m/m volatility made all the more marked of late by swings in the weather. Furthermore, construction is still contracting with the ensuing drop in properties for sale possibly explaining the recent recovery in house prices. That latter recovery, alongside wage gains of around 5% (that may extend into 2025), has boosted real household incomes, but this has yet to see consumers more willing to spend (Figure 5). All in all, the economy is still feeling the pinch of both monetary tightening and weak growth elsewhere in W Europe and beyond, the former highlighted by a continued sharp slowing in private sector credit growth. But the slightly better-than-expected Q1 has persuaded us to upgrade the GDP outlook, with the growth rate this year revised up 0.2 ppt but still to just 0.6%, this being a little below both consensus and the recently revised Norges Bank outlook. Regardless, a gradual recovery is still seen in H2 and this should continue into 2025, albeit with nothing more than a below trend rate of 1.3% and with downside risks attached to this consensus-like but unchanged forecast.

This view very much reflects 2024 seeing a second successive year of negative fixed investment, and one that extends beyond weak construction. But in contrast to optimistic Norges Bank thinking, the gloom regarding households remains; after a clear fall in consumer spending last year, we do not see any recovery in 2024 and only modest growth next year. This is especially as the recent rise in house prices is fragile and unemployment is starting to rise. This is likely to add to the fall in inflation now very much unfolding, with the CPI-ATE measure continuing to undershoot Norges Bank projections, albeit a little above our expectations in the last few months. Hence, we have revised higher the anticipated average rate for CPI inflation this year to 3.3%. This also encompasses the headline rate hitting 2% by H1 next year and then remaining there through 2025 as productivity and lower profit margins offset wage pressures. This is hardly surprising as the next two years should see an output gap persisting and averaging nearly 1% of GDP. Indeed, more reassuring signs are already emerging increasingly on a broad front too, with m/m adjusted data increasingly showing signs of buckling. Our computed core measure in which food is excluded from the familiar CPI_ATE figure (Figure 1) shows recent seasonally adjusted m/m dynamics to be running at pace already consistent with the 2% target albeit with some noise in the latest (May) numbers. And this is in spite of the impact of rental inflation (around 17% of the CPI) running still at over 4% y/y, implying headline inflation ex rents now at 2.5%.

Figure 5: Household Less Worried but Still Unwilling to Spend

Source: Stats Norway

The Norges Bank Board’s clear caution meant it was hardly a surprise that this month it left its policy rate at 4.5% for a fourth successive meeting. Perhaps more notable was that it was more explicit in stressing ‘policy to stay on hold for some time ahead’ rhetoric, this backed up formally with an updated policy outlook that now sees no rate cut until early 2025, some three months later than hitherto. This is in spite of a downgrade to the Board’s 2024 CPI outlook reflecting a broad undershoot of its inflation expectations. Instead, policy is being shaped by an upgrade to the wage outlook which results in the Board’s higher CPI projections out to 2027 and where the CPI-ATE measure stays above the 2% target. Even so, the revised policy outlook sees a slightly softer policy rate at the end of the forecast horizon, the question being whether this is seen being a terminal or even neutral rate. We instead think continued inflation weakness relative to Board thinking in coming months will deliver at least one cut by end-year and maybe over 100 bp in 2025, albeit still some 50-75 bp higher than we envisaged three months ago!