Eurozone Outlook: Resilience or Irrelevance?

·· Yet again, and amid what may still be tightening financial conditions and likely protracted trade uncertainty, we have pared back the EZ activity forecast for 2026. However, the picture this year appears to be slightly better but this is largely a distortion and we think that the economy has actually been growing below-par on an underlying basis, with downside risks persisting rather than showing resilience.

· All of this reflects the competing forces of planned defense and infrastructure-induced fiscal expansion in the EU against the activity and the likely disinflation damaging tariff threat from the U.S. This juxtaposition of near terms risks and medium-term hopes has persuaded the ECB to pause, if not end its easing, but we forecast two more cuts in this cycle to a 1.5% ECB deposit rate, possibly more deferred than previously thought.

· Details of the well-flagged fiscal expansion are still unclear but we feel it may be less sizeable, take longer to exercise and be less broadly spread across the EZ than perhaps the European Commission would have us believe. It may not trigger a fiscal crisis but could mean financial conditions remain tighter for longer than otherwise!

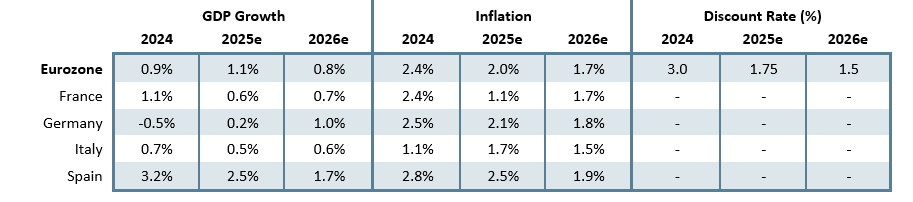

Forecast changes: Compared to the last outlook, we have on balance made no net change to the overall EZ growth outlook, with a slightly less-fragile further recovery for 2025 but a paring back for growth in 2026. More notable, then is the hardly-revised and still-soft EZ HICP inflation outlook in which the target is undershot on a sustained basis into late-2025 and beyond.

Our Forecasts

Source: Continuum Economics, Eurostat

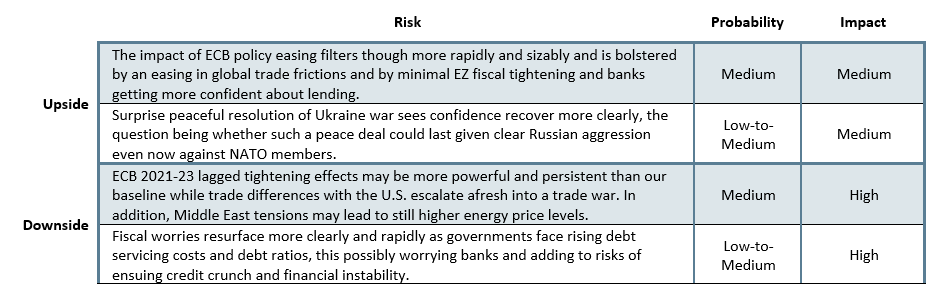

Risks to Our Views

Source: Continuum Economics

Eurozone: Fragility Not Resilience

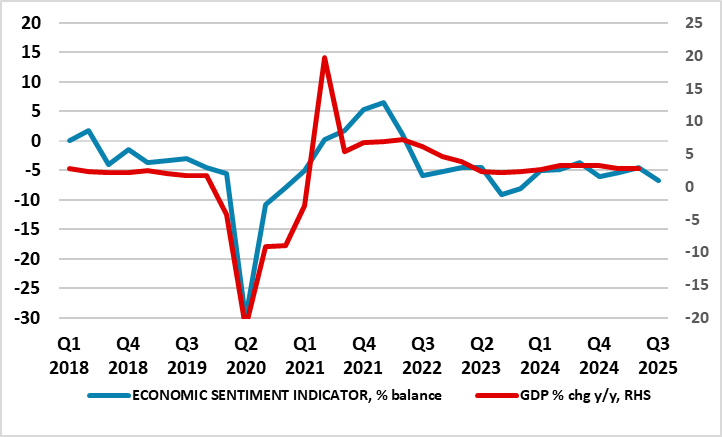

For an economy that has seen repeated upside GDP surprises, and apparently above trend growth, now some 1.4% in the year to Q2, GDP data do not seem to have much impact in derailing disinflation. But such data has made the ECB less worried about the economy, now very much repeating how the EZ is showing resilience. Instead, that above-trend growth in the last year has come alongside what has been significant disinflation, this very much supporting our long-held view that weaker price pressures of late have been mainly supply driven and thus where weak(er) demand ahead (household) spending is seen with further growth of just over 1% this year and next) could prolong, if not accentuate, such disinflation. Notably though, a weak(er) demand picture is reinforced both by the marked downgrade to the recent German economic backdrop and what looks like a sizeable involuntary inventory build in France. Indeed, both suggest more overall EZ spare capacity. Moreover, it is still uncertain how businesses will react to the so-called trade deal with the U.S. - in what seems to have been a fully-fledged political capitulation to the U.S. the EU, it seems, is accepting an agreement that would see an almost-blanket reciprocal 15% tariff on its exports to the U.S. This is not as onerous as we feared but still a little more severe than in our baseline forecast, and where we have not made any adjustment for what may be a re-routing of Chinese exports to Europe, damaging growth for the latter and adding to downside price pressures into 2026 – NB: import prices have already fallen in each of the last five months of data. We see largely flat GDP growth for this and the next quarter, with 1.1% 2025 average growth but somewhat less in 2026 at 0.8% involving 0.1 ppt upgrade and downgrades respectively but with downside risks!

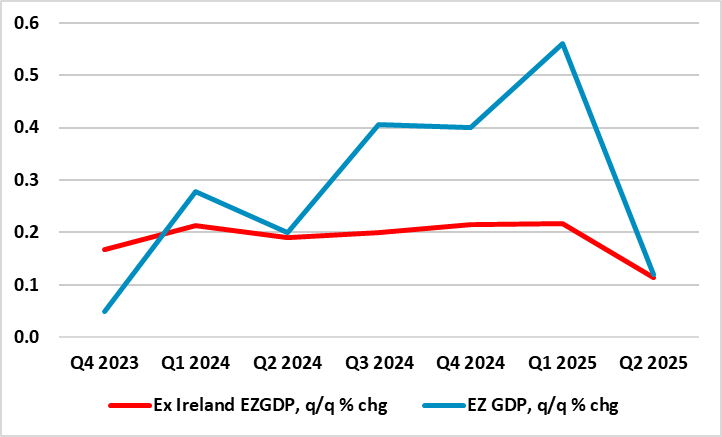

As for the EZ economy’s resilience of late, perspective is needed, perhaps more so than usual. As we have stressed before, recent GDP data gains have been predicated on both a surge in Irish GDP as well as what was seems to have been an inter-related EZ export jump in anticipation of the US tariff imposition from April. But as Figure 1 underlines, ex Ireland, EZ GDP has averaged around 0.2% q/q in the last 6-8 quarters, a run of data very much consistent with our 2026 GDP picture where we see no repeat of what has been profit-swing related Irish growth of late. The outlook is complicated by diverging business surveys with the EZ PMIs and European Commission survey data offering diverging signals, the Commission data very much undermined by a weak and possibly understandable manufacturing response that very much conflicts with the recent ECB assertion that ‘surveys point to an overall modest expansion in both the manufacturing and services sectors’. As suggested above, given what is a very unfavourable trade deal with the U.S. we tend to identify more with the still sobering outlook (ie very much below par) offered by the Commission data, especially as continued weakness may be in the offing as the trade agreement takes effect!

Our still soft and below consensus outlook reflects a host of imponderables, some to do with the timing of likely fiscal and defense initiatives; some to do with to what degree they may boost EZ growth only modestly due to the likely large import content to begin with and also the extent to which they may be tempered by what may be more sustained tightening in financial conditions (see below) due to interest and exchange rates being higher than otherwise would be the case – banks still show wariness about lending to firms, something that will add to restrained regarding capex over and beyond uncertainty. Indeed, there is also increased uncertainty emanating very much from political divides and policy paralysis in several countries (clearly France) and where, as suggested above, greater fiscal consolidation measures from several countries that will continue beyond next year this even if EU-wide fiscal rules are loosened as even Germany is now calling for.

As far as defence is concerned, fiscal restraints are clearly to the fore and hindering a fiscal boost that is hoped for. ReArm is partly to be financed by relaxed EU fiscal rules allowing the use of national escape clauses for up to 1.5% of GDP per year for defence purposes, allegedly enabling additional spending of about EUR 650 billion (4.3% of euro area GDP) over the next four years. But to date only a third of EU member states have signed up due to fiscal constraints!

Figure 1: A Tale of Two Economies

Source; Eurostat, CE

Fiscally, having tightened significantly in 2024 on account of the withdrawal of a large part of the energy and inflation support measures, we now see the fiscal stance continuing to tighten into 2026. Indeed, with an EZ headline budget gap that may rise further above 3% of GDP into 2026, the fall in the EZ government debt ratio to 88.5% of GDP last year will likely soon be followed by a rise toward 91% in 2026. This is especially given that the EU Commission’s fiscal plan could ultimately mean the EZ primary deficit rising clearly from just over 1% of GDP this year thereby raising questions about fiscal sustainability afresh.

As for the trade balance, the anticipated cyclical, and possibly structural, recovery in imports into 2025, as well as what may be a weak global economy weighing on exports, will also mean that the improvement in the current account surplus last year (at around 2.6% of GDP) may reverse into 2026. This is also a headwind to GDP growth.

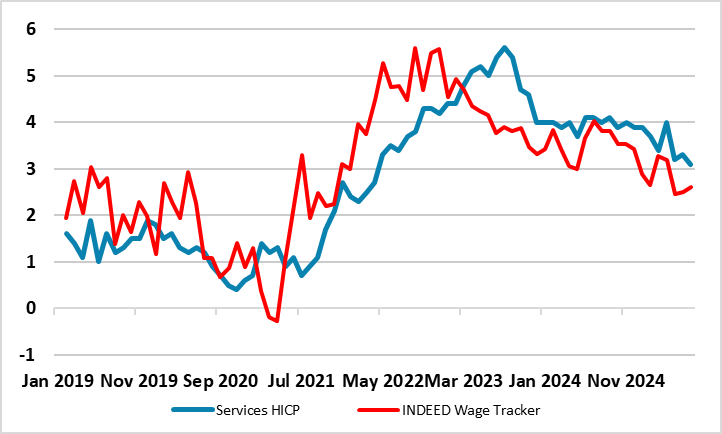

As suggested above, amid what has been a disinflation process so far very much supply driven, but encompassing what has already been a marked softening of underlying inflation, we still envisage headline HICP staying below 2% more durably into next year with the core not far behind and then remaining below target through 2026. This picture is little changed compared to the previous Outlook, but encompasses evidence of softer cost pressures, especially in regard to wages. Indeed, the omens point to services inflation slowing even further in due course (Figure 2), something we think will emerge more visibly into 2025 as wage growth slows to pace consistent with the inflation remit.

Figure 2: Wage Pressures Moderating Clearly and Pulling Down Services Inflation

Source: Bloomberg, Eurostat, % chg y/y

ECB: Nearing But Not Yet the End?

A second successive stable policy decision was the almost inevitable outcome of this month’s ECB Council meeting resulting in the first consecutive pause in the current easing cycle, with the discount rate left at 2.0%. Also as expected, the ECB offered little in terms of policy guidance; after all, in July the Council suggested it would be ‘deliberately uninformative about future interest rate decisions’. Little may be gleaned either from the updated economic projections which only goes to show that an upward revision to the growth picture can be associated with a perceived drop in underlying price pressures. All of which implies that even with growth risks seen as more balanced, this does not mean that disinflation cannot continue. The ECB may now be in a mode in which something will now have to trigger further easing, but we think this will occur given tariffs and what are still tight financial conditions likely to mean an undershoot of ECB growth thinking. Thus, data dependence will probably trigger two more 25 bp cuts, probably late this year and early next!

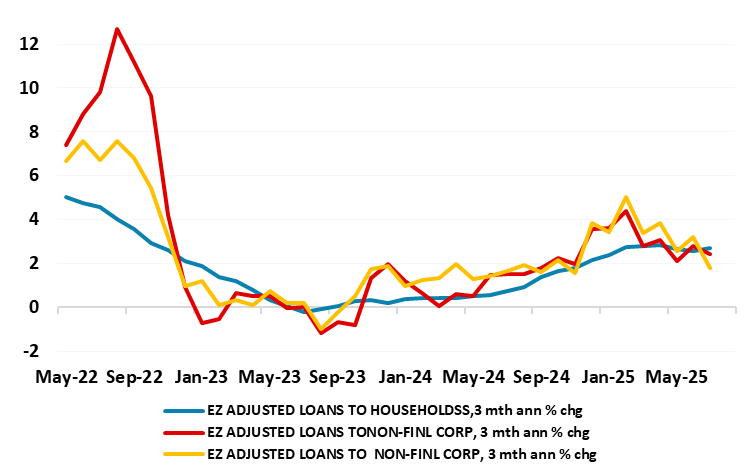

Figure 3: Credit Growth Slowing Afresh

Source: Bloomberg, ECB

Even if ECB easing has ended, it is hard to see any early policy reversal, not least as it is difficult to see HICP inflation picking up strongly given both weakening jobs and wage growth and both direct and indirect tariff repercussions. The ECB may also be wary that any early hiking would only accentuate fiscal plights in some countries, thereby making what are currently budget problems turning into possible fiscal crisis. It will also be wary that it could add upward pressure to the euro, already at record highs in trade weighted terms, this clearly seen as disinflation issue for the ECB.

But perhaps the clearest rational for not hiking at anything like the timing markets have started to contemplate is the mere fact that existing easing has yet to feed through fully to either households and particularly firms’ borrowing rates. Indeed, it is worth noting that while the ECB policy rate has fallen by two ppt, the effective rate for households has fallen by 1.7 ppt but that for firms by a meagre 75 bp. All of which raises the issue of how restrictive are current financial conditions. The idea that policy is neutral and conditions mellowing is something we would challenge given that real credit growth is still negative and where nominal growth rates have slowed clearly of late (Figure 3) amid what still seems to be wariness from banks about lending, particularly to export orientated firms.

Germany: Tariffs vs Fiscal Expansion

The upgrade to 0.2% of the GDP growth this year (from -0.2% three months ago) is illusory as it reflects a bounce from a deeper recession for both 2023 and 2024 that, along with the fresh Q2 drop this year, implies an even larger output gap that makes us even more confident of continued disinflation – NB: the revised GDP backdrop is now more in line with the drop in IFO-compiled capacity utilisation. Indeed, we retain our below consensus 2026 CPI picture, this reinforced by a 0.3 ppt downgrade to next year’s GDP projection to 1.0%. This partly reflects the now more clarified and slightly reduced U.S. tariff threat (and possibly protracted) uncertainly while the hopes for marked fiscal expansion alongside a distinct defence build-up looks more a story for late next year and into 2027. After February’s snap election, new Chancellor Merz and his conservatives (in coalition with the centre-left Social Democratic Party) swiftly moved to pass landmark legislation loosening Germany’s so-called debt brake. While this marked dilution of previous self-imposed fiscal austerity allows for massive spending on defense while unlocking EUR 500 billion in borrowing for infrastructure, major budget gaps still looms and the Finance Ministry has warned of tough spending decisions in the next several months.

Indeed, it would be wrong to overstate the German debt surge, certainly in timing. Multiple challenges will slow down the government’s spending plans. First, there is the (In)famously slow procurement process for military equipment which is widely regarded as overly bureaucratic. Another problem are the capacity constraints in the German and European defence sector - Rheinmetall, Germany’s biggest manufacturer of military equipment, had last year a turnover of less than EUR 10bn and its order books are full for years to come. Similar constraints may also hamper infrastructure investment so we suggest the fiscal reforms need to be accompanied by administrative reforms which may be drawn out by coalition differences. Moreover, even under current ‘plans’ in terms of size, the planned deficit-financed infrastructure fund worth EUR 500bn (ie around 11% of GDP) is to be spread over a ten-year period.

The bottom line is that a German budget gap that otherwise looked to be around 2% of GDP could turn into one of well over 4% (both headline and structural) probably not this year but into and beyond 2026. As a result, the government debt ratio would rise from its current 63% of GDP to above 80% over the next decade possibly without negative repercussions – not least as Germany has already suggested EU-wide fiscal rules (which this initiative compromises) need to be relaxed. But added government spending will boost imports even if defense has an aspiration attached of being directed towards domestic/European producers. As a result, it looks very likely that the circa-6% of GDP current account surplus likely this year will be reduced down towards 4% in 2026 – both helping growth elsewhere and politically speaking addressing the source of what may be growing trade tensions and trade wars.

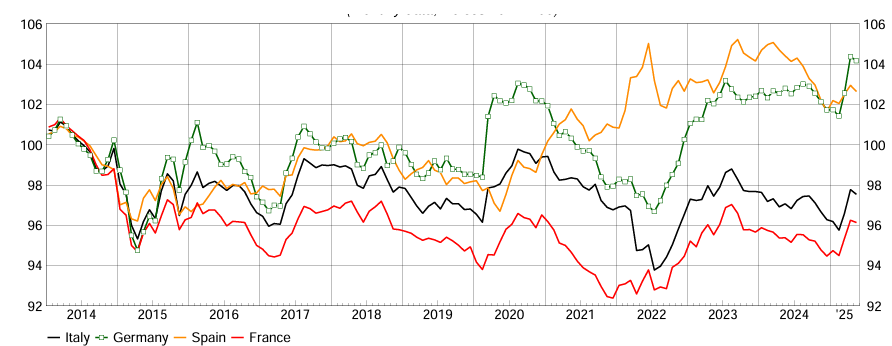

But added uncertainties include the stronger euro adding to already deteriorating competiveness (Figure 4) (particularly perturbing the Bundesbank), helping explain the current economic weakness that forward looking indicators (ie orders) suggest will persist in both industry and the equally recession-bound construction sector. In 2025, actual earnings will still see weaker growth than negotiated wages, the latter down to below 3% from 4% last year, mainly a result of lower performance bonuses and even by likelihood of a similar result in 2026. There are some brighter signs, however. Lending to households for house purchase, continues to recover and this has helped revive some household consumption to a rise of around 1% this year (more than double that if last year), this also benefiting from strong wage growth. But with the labour market remained weak and joblessness on the rise little further pick-up is in store for 2026.

Figure 4: German Competitiveness Deteriorating Clearly and Relatively (2014=100)

Source: ECB, CEPII, Eurostat, IMF, OECD, UN data and national statistics based on producer prices of manufactured goods. An increase in an index indicates a loss of competitiveness.

France: A Political (and Fiscal) Crisis Still Bubbling on the Back Burner

That France has seen the departure of yet another prime minister was no surprise, hence why financial markets took the confidence vote loss causing this in its stride. The now plausible option of a fresh parliamentary election is unlikely to be used, not least as it may again leave the Assembly’s three-way fragmentation largely unchanged, Admittedly, French sovereign spreads and yields have risen in the last few months, but even so the actual level of bond yields remains well below that of the UK despite higher debt and deficit in France. We suggest this is largely a result of France being part of the EZ and where the ECB offers some protection – albeit where France’s current politics-driven fiscal woes suggests the much vaunted TPI tool is highly unlikely to be used. Instead, it is the current low level of ECB policy rates that is cushioning the French market on a relative basis. Thus, given our view that policy rates will still likely fall further, this latest French government can afford to kick the fiscal can further down the road. However, this may be only for the time being as when the ECB starts to tighten afresh (or even visibly contemplate this), market scrutiny of France will intensify, especially as this may coincide with heightened French political uncertainty into 2027 related to the then-likely presidential election. The question is whether French fiscal fragility may act to dissuade the ECB from early tightening!

Yet again, we have made little change to the already soft and fragile French economic outlook for this year or next, albeit seeing GDP growth a notch higher this year to 0.6% but revised down 0.2 ppt 2026 (to 0.7%). The latter partly due to tariffs and trade worries but also a little below current consensus thinking, albeit where the latter has undergone a clear downgrade in recent months. But there is an array of factors at work, mostly negative. Admittedly, the planned German fiscal expansion was and remains very good news for France. As important is Germany’s call for EU-wide fiscal rules to be relaxed, this all the more important given the large budget deficit that France is facing as fiscal restraint continues to be the underlying theme. In fact, we do not see France being a major part of any clear defense-based fiscal expansion given its adverse budgetary backdrop and outlook. Indeed, the European Commission has made clear that countries should consider ramped up defense spending – ‘if they have the fiscal space’. And even with what may soon be watered down EU fiscal rules, a French budget gap (both headline and structural) that may be over 5% of GDP even beyond next year risks seeing the debt ratio (likely to rise to toward 120% of GDP next year) rise even further on the back of high primary deficits and rising interest payments, whereas the debt-reducing effect stemming from nominal growth is projected to moderate compared to recent years. In addition, the political situation hardly bodes well for the fiscal picture and the new administration is already watering down its predecessor’s proposed EUR 44 billion of spending cuts and tax hikes which somewhat optimistically would have narrowed the 2026 deficit to 4.6% of GDP from an expected 5.4% this year – hence fresh rating agencies recent downgrades.

With this in mind we reiterate that France does not (yet) face a fiscal crisis but still faces a tighter fiscal stance into 2026 and beyond. Admittedly, given France’s large defense industry (providing almost 10% of global arms exports), it should be beneficiary of added EU spending – hence its demands that the EUR 150 bln proposed loans from the EU be not be frittered by buying from outside the EU.

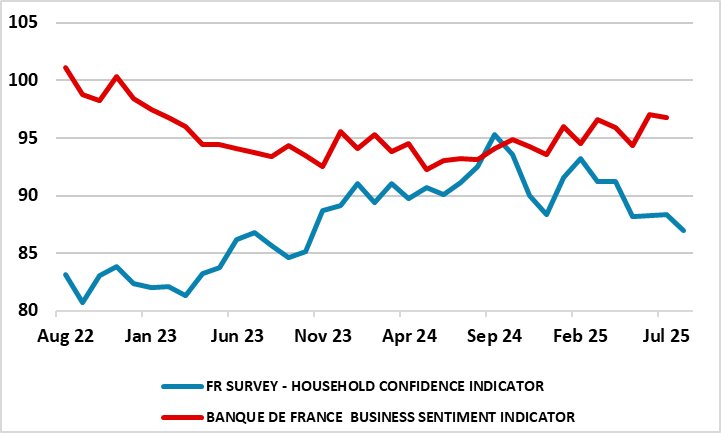

As for details, the anticipated growth weakness reflects both the contractionary fiscal stance coupled with economic and policy uncertainty, both domestic and from the global environment. The current recovery in imports will detract from GDP growth in 2025 and probably in 2026, while private investment is projected to be subdued, as the surge in uncertainty weighs on capital expenditure. In contrast, consumption is expected to be bolstered by increases in real wages, but the saving rate should remain high at over 17%, against the background of fresh falls in consumer confidence (Figure 5).

However, this soft growth outlook will reinforce the broad disinflation already very much evident. In fact, price pressures have fallen more than we thought three months ago and we now envisage CPI inflation at 1.1% this year (ie pared back by 0.1 ppt) and likely to stay under 2% through 2026, albeit with risks on the upside from possible fiscal measures. This inflation picture will not help the fiscal side and reflects a continued reining in of pricing power and a rise in the unemployment rate back toward 8% into 2026 and where companies are likely to see profit margins fall further!

Figure 5: Fragile Business and Consumer Confidence

Source: Bank of France, INSEE

Italy: Remaining Out if the Policy Limelight

For a second successive Outlook, we see little rationale to alter our growth outlook which is now consensus-like. There is a 0.1 ppt downgrade to this year due a slightly softer than expected Q2 GDP outcome. Admittedly, this year’s projection of 0.5% would be down on the less-miserly 0.7% outcome of last year but this is partly base effects as still crucial in this outlook is the consumer, where spending (at around 0.5%) is likely to be as anemic due to restrictive financial conditions but mainly to the wind-down of the Superbonus building tax credit (a generous tax incentive for housing renovation). But amid what has been a still-falling jobless rate (despite record-high labor force participation) and actual real wage growth (nominal gains of over 3% are seen again in 2025), the consumer should see somewhat faster spending into 2026 but not quite up to the 1% gain we thought possible three months ago, even given CPI inflation slowing to 1.5% into 2026 (little changed from three months ago). The question is whether this recovery will fuel a further pick-up in imports, this one reason for a small downgrade to the 2026 GDP picture to 0.6%. As a result, we see the current account surplus staying just over 1% of GDP but with upside risks at time goes by as Italy’s large arms exports (5% of the global market) benefits from rising EU defense spending and where import prices may continue to drop.

These forecasts are very similar to those updated by the Bank of Italy (BoI). In this regard, and as we underlined three and six months ago, Italy is unlikely to be major victim of now detailed U.S. trade restrictions in the coming two years, save for some damage to its transport sector: BoI estimates suggest U.S. tariffs at current levels and amid uncertainty remain high, GDP growth might be over 0.2 percentage points lower than otherwise this year and next.

But there are downside risks as the outlook is still sobering an outlook very much squaring with current and somewhat soft business survey data – the BoI’s EuroCoin indicatior remains close to zero. Moreover, bank lending is showing still negative growth in the corporate sector – this possibly as much a result of bank wariness amid a fresh rise in non-performing loans of firms. Another downside risk is that the wind-down of the Superbonus actually triggers a larger and more persistent contraction in housing investment, the latter having been a key source of growth over 2021-23. But on the upside, the acceleration in public investment related to the National Recovery and Resilience Plan could boost growth in 2025-26 more than expected, not least as a full utilization of New Generation EU funds implies that such-related spending needs to be ramped up from about 1% of GDP in 2024 to about 2.5% of GDP on average over 2025-26.

Lastly, fiscal worries seem contained. Partly this reflects genuine fiscal improvements, albeit largely a one-off result of the unwind the Superbonus scheme. However, the budget deficit is forecast to edge down a further notch to 3.3% of GDP this year, on the back of a marginal improvement in the primary surplus and unchanged interest expenditure as a share of GDP and a small rise in the tax burden is expected to rise marginally. In 2026, the deficit is expected to fall to 2.9% of GDP and the primary surplus to reach as high as 1% of GDP on the back of moderate primary expenditure growth. Even so, the European Commission warns that, even into 2026, a continued rise in interest expenditure to 4% of GDP will mean the debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to increase one ppt in both 2025 and 2026 to over 138%. Thus, we still feel the current sovereign spread is too low but not significantly so.

Spain: Climate Change Already Evident

Spain is very much in the hot seat when it comes to climate change. Already it has suffered water stress as droughts last longer, rainfall (when it occurs) is heavier but less predictable while heatwaves are more frequent and wildfires are more destructive and widespread. And this is taking an economic toll, hitting key sectors such as agriculture, energy and tourism. Indeed, desertification poses a broad climate risk for Spain as it can not only affect economic activity but also bank lending, insurance and therefore even financial stability.

In response, the EU has presented a Water Resilience Strategy, which implies that Spain must triple its current level of water investment management to ensure water resilience, something that may cost up to 0.5% of GDP annually out to 2030. It is unclear whether this will ‘crowd out’ other areas of investment, but climate change is buttressing what seems to be very clear shifts in what has been driving GDP growth in recent year, posing both risks and uncertainties ahead. Indeed, while recent growth has been driven by demographics, government expenditure and foreign tourism, the latter up some 40% compared to pre-pandemic levels, but is now (as suggested above) waning. Indeed, not least due to high prices, over-crowding and the growing resistance from locals, international arrivals, while up over 4% so far this year, are growing far slower than in 2024, this possibly likely to help dampen overall inflation given that the rate in tourism services inflation is currently twice as high.

Business survey data suggest that solid GDP growth in H1 will continue but probably slow (Figure 6), with perhaps one key worry being the extent to which hitherto robust service sector activity, that has been the backbone of recent GDP growth, is falling away, given that the EZ more recently has been driven solely by services and it is the fact that Spain’s economy has a much larger share of services in its make-up compared to the EZ average (75% vs 70%) that has helped the country to out-perform. Even so, Spain has been considered to be less vulnerable to likely US tariffs with less than 1% of GDP stemming from exports to the U.S., less than half the EZ average so that the higher than expected 15% rate now being levied may have only a modestly greater than previously expected impact. The question is whether the consumer sector can move centre stage in supporting the economy, but if so, will this partly be offset by a likely further pick-up in import demand

Regardless we have upgraded the GDP picture largely reflecting the strong Q2 outcome. Admittedly, still very much at the top end of the EZ growth ladder and where Spain’s economy by end 2026 is likely to over 10% larger than it was by end-2019, twice that of the rest if Eurozone. That gap may increase further, not least after a 3.2% GDP surge in 2024, growth slows to ‘only’ a 2.5% in 2025 (revised up 0.5 ppt) and then to an unchanged 1.7% in 2026. As for details, additional housing wealth, lower inflation and still solid jobs growth may mean that household spending does become the mainstay of growth into next year, partly offsetting the lags likely from net trade and the public sector. Indeed, the unemployment rate may continue to fall, although its reduction will be moderate from 11.4% in 2024 and below 10.5% in 2026. Regardless, we still see a largely unchanged current account surplus of around 2.5% of GDP both this year and through 2026.

As for the weaker 2026 picture, there is going to be no rapid defence build-up, amid an aversion to the military, all complicated as Spain may faces political uncertainty and even possibly snap elections amid the current corruption scandals. While looking better due to rapid nominal growth, it still has its own fiscal problems with structural budget gap of just over 3% of GDP last year, albeit with the actual gap likely to fall below 3%, all keeping the debt ratio at around, if not slightly below 101% of GDP.

Figure 6: Surveys Suggest Some Slowing Underway?

Source: European Commission, INE

As for CPI inflation, we expect the underlying trend to be one of continued consolidation. Indeed, we see inflation slowing to an average of 2.5% this year (a slight upgrade due to swings in energy prices) but with the projection of 1.9% for 2026 down a notch. This reflects some slowing in terms of services inflation, and subdued wage pressures, the latter possibly reflecting fresh strength in labor force growth.

I,Andrew Wroblewski, the Senior Economist Western Europe declare that the views expressed herein are mine and are clear, fair and not misleading at the time of publication. They have not been influenced by any relationship, either a personal relationship of mine or a relationship of the firm, to any entity described or referred to herein nor to any client of Continuum Economics nor has any inducement been received in relation to those views. I further declare that in the preparation and publication of this report I have at all times followed all relevant Continuum Economics compliance protocols including those reasonably seeking to prevent the receipt or misuse of material non-public information.