Western Europe Outlook: Underlying Price Pressures Ebbing

· In the UK, we have upgraded 2025 GDP growth by 0.1 ppt to 1.3%, but pared back that for next year by a two notches to a very sub-par 0.6%. We think the weak(er) labor market will accentuate somewhat refreshed disinflation allowing the BoE to ease further in 2026 by around 75 bp to 3.00%.

· Sweden has seen a clear easing in both its monetary and fiscal policy stances, but despite a likely better 2025 outcome, the growth outlook still seems fragile for now and where the Riksbank’s activity optimism still looks overdone. Even so, we are forecasting solid growth in 2026, which should see the Riksbank holding rates.

· In Switzerland, the tariff impact may now be less sizeable but will still notably slow growth and add to disinflation, although where the latter may avoid turning negative. Even so, the SNB is most likely done, easing wise, unless (in the unlikely event) already soft inflation turns persistently negative.

· In Norway, there are signs that the economy has started to slow, making an already negative output gap persist, something we think makes the Norges Bank’s caution about stubborn inflation overdone.

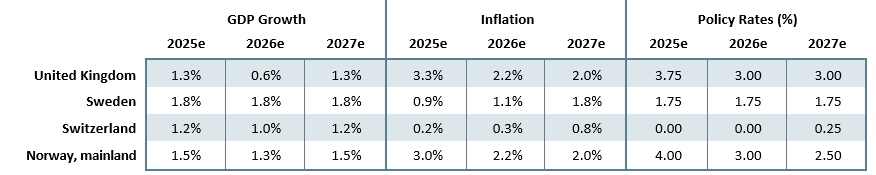

Forecast changes: Compared to our September Outlook, 2025 growth forecasts have been largely upgraded except for Norway and Switzerland. But the 2026 picture looks largely worse, albeit with 2027 likely to see something a little better growth-wise. Regardless, we still suggest a durable return toward (or below) for all inflation targets into next year so that our policy outlook is little changed save for a little higher in Norway and a little lower in the UK!

Our Forecasts

Source: Continuum Economics

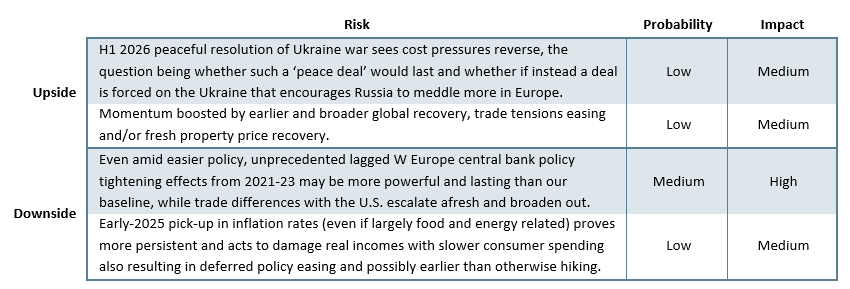

Risks to Our Views

Source: Continuum Economics

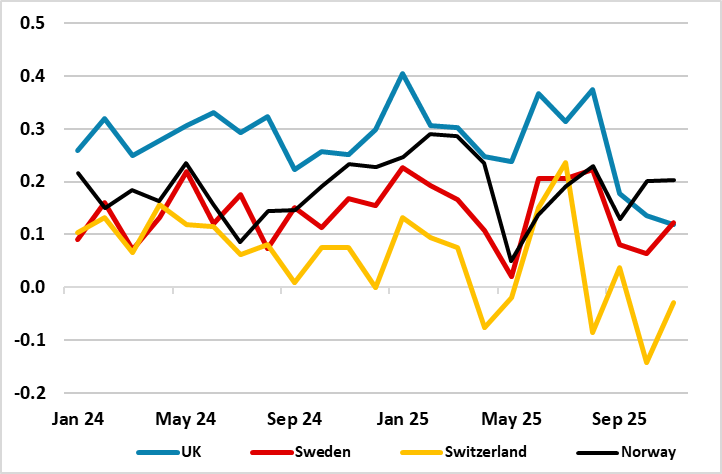

Identifying the Appropriate Inflation Measure?

While there have been spikes in inflation data in at least three of the W Europe economies this year, Switzerland being the clear exception, most of this has been related to special factors, not least food prices this being important in Norway and Sweden as the targeted inflation measure includes the latter. As Figure 1 shows, Switzerland has instead seen more weak price readings, actually undershooting SNB expectations somewhat. But even in the UK price data have become a little lower and we would assert that looking at core inflation in all four economies on a uniformly basis, disinflation has re-emerged, however much some of the respective central banks may be downplaying it.

Regardless this policy blindness has accentuated the manner in which monetary easing has proceeded at very different levels and speeds across the four W European central banks, the Norges Bank being the notable latecomer and the BoE somewhat slow. But we think both will catch up somewhat in the course of the year

Figure 1: Core Inflation Pressures – Low Or On the Way Down

Source: CE, % chg mm, 3 mth mov avg (all measures are ex food and energy)

UK: Downside Risks Becoming Downside Reality?

As evidence of actual current economic weakness builds (and broadly so from both hard data and surveys), we have downgraded our already soft and below consensus outlook further. This is in spite of the recent Budget not delivering feared further immediate fiscal tightening. In fact, there is a little but short-lived fiscal loosening, based around higher welfare spending which will help the GDP profile from H2 next year, though where budgetary uncertainty still seems to be the major factor in terms of existing and likely lingering damage to sentiment (households and firms). Indeed, the now likely contraction in current quarter GDP may only accentuate such worries with opinion polls showing very high levels of dissatisfaction, not least with the government’s handling of the economy.

That likely Q4 2025 contraction has put a hole in our already weak GDP outlook, which has seen the strong H1 of this year fade markedly in H2. Even so, for 2025 we have upgraded growth by 0.1 ppt to 1.3% though with twice as large a downward revision for next year to a below-par and below consensus 0.6%. Notably, the latter masks a gradual q/q improvement through the year so that end-2026 growth is around 1%. That puts the higher 2027 picture we now have with growth of 1.3% in better perspective and where the impact of both monetary and fiscal easing is reflected but with the risks we highlight below. Regardless, uncertainties remain high and twofold. Firstly, given diverging and conflicting data, we remain unsure as to the current state let alone how activity may pan out. However, what have been somewhat diverging data readings, are coming together in a more uniformly soft backdrop and outlook. The weaker 2026 picture reflects several factors, not least that lagged monetary policy tightening effects (both conventional 2021-23 and unconventional) may be biting harder than at least the BoE has factored in. Indeed, policy is still biting the economy through the credit channel, where weaker signs are already re-emerging as highlighted by fresh news of an ailing housing market and slower private sector credit growth.

But, over and beyond what are likely to be persistent trade worries and uncertainties, the main factor is of course the growing evidence that recent tax rises and fiscal swings have curtailed, if not reversed, hiring. Moreover, the risk is growing that the fiscal tightening now envisaged from late 2027 may do little to rein a budget gap of nearly 5% at present, let alone prune it back to below 2% as the official projections suggest, thereby also risking flouting the fiscal rules. Admittedly those rules could yet be diluted by political tensions within the ruling Labour Party, the question being whether this would be counter-productive as an adverse gilt market reaction to a budget deficit staying above 4% would compromise the falling debt rule and may merely lead to a further tightening in financial conditions.

All of which to us means that this year’s weak consumer spending picture may continue with growth in 2026 not much better that the 0.8% growth likely this year. A weak labor market and tax concerns are restraining consumers. Meanwhile, an added headwind, but possibly now less forcefully, is provided by a weaker overall European growth backdrop, most notably for the EZ although this may be more short-lived that previously envisaged given the fiscal and defense initiative the EU is trying to put together. Regardless, we see imports recovering (further) which, together with the fragile export picture, points to a wider current account deficit than that seen in 2024 (ie around 2.75% of GDP) or 2025.

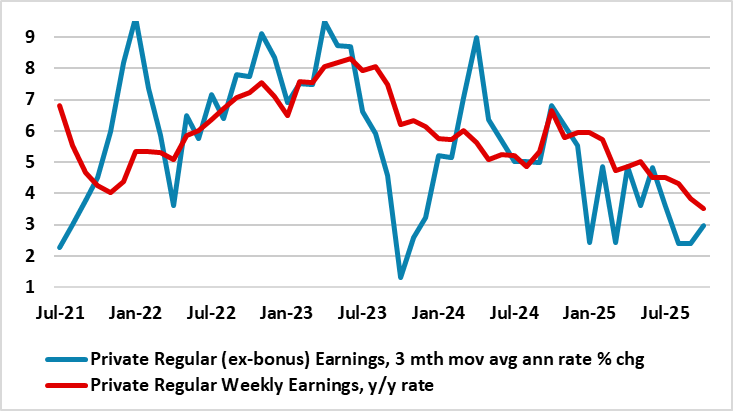

This below-par growth outlook into and through 2026 may already be refreshing the disinflation signs seen of late which we suggest have previously been a result of an easing in supply pressures. We still see a 2026 outlook with a little changed 2.2% CPI projection and then an on-target 2% in 2027. Underscoring this is our view that the labor market is both weak and still loosening far faster than the gradual manner explicit in BoE thinking. This is based not on any expectation of softer price and wage pressures, but a continuation of the clear softening that is now emerging in both. This is especially so looking as recent adjusted m/m data. Recent such data suggest that core and services CPI numbers may already be running at rates more consistent with the 2% target, while wage (earnings) data may have slowed even more markedly (Figure 2).

One hardly new but emerging factor that may affect and/or complicate the outlook is the possibility of the UK undoing Brexit – at least to some degree with the issue possibly gaining momentum in the coming two years. This may need (and reflect) a change of prime minister, but a return to the customs union or single market is something advocated by some Labour policy advisors and is also now electorally sound: a majority of voters now view Brexit as a mistake and would put clearer distance between the government its main opposition threat the Reform Party.

Figure 2: Weaker Wage Pressures Increasingly Evident?

Source: ONS, CE

As for the BoE, that the MPC delivered a sixth 25 bp rate cut (to an almost three-year low of 3.75%) was hardly in doubt. We were surprised that amid the recent run of weak data, that there were (again) four dissents with Governor Bailey switching sides. Notably, in a clear combative overtone, at least some of the hawks are unwilling to accept that recent data means disinflation may have intensified with Chief Economist Pill actually questioning whether further cuts should occur. But overall, the majority do seem to back additional cuts but where they will be gradual and likely to remain ‘close calls’ in future. Admittedly, persistent sizeable dissents through 2026 may complicate policy making. But we think those dissents will be tempered as the MPC vast majority recognises the already ample signs of a weaker demand and a looser labor market backdrop, and where headline inflation may fall back to the 2% target before mid-2026, at least for a period. So far, this is purely evident to only two MPC members (Dhingra and Taylor) but even they not acknowledging clear signs of both price and wage pressures having subsided markedly. Thus we retain our below-consensus projection of Bank Rate falling to 3.0% by end-2026.

Sweden: Waiting for Easier Policy to Filter Through

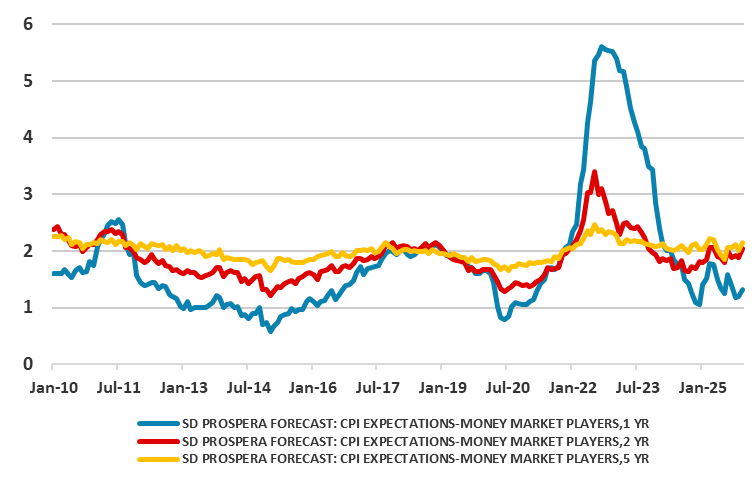

A better than expected Q3 GDP result, allied to an array of much softer recent CPI readings, may have policy makers currently sampling seasonal produce with more glee than otherwise, but they would be wise not to get complacent. Admittedly, soft inflation numbers look likely to remain the norm, with a further drop all the more likely into H1 2026 due to a now scheduled cut in VAT for food in April 2026. This will knock some 0.5 ppt off all main inflation measures until it is reversed at end-2027. This is only likely to reinforce the disinflation process, where despite some recent upside surprises, to us, the underlying picture as presented by adjusted targeted (CPIF) monthly data has been reassuring. This is despite the impact on this measure of food inflation now running at around 4%, albeit creating a marked base effect next year, allied to the tax cut. Indeed, an ex food and energy core measure (similar to that used in the EZ) shows persistent sub-target price pressures (Figure 1). Thus we have reduced our 2026 CPI projection further from 1.4% down to 1.1% and we see targeted inflation (CPIF) moving and then staying below 2% through 2026. However, mortgage rate induced base effects will pull the headline higher next year and then into 2027, but where headline and CPIF may average some 1.8%. Regardless, this picture is being acknowledged (Figure 3): inflation expectations measures are back at or below target and pre-pandemic averages (for shorter-tem measures).

Apart from those special factors, the soft inflation picture reflects a persistent output gap, though one that largely halves from the circa 2% of GDP this year by 2027. This is on the basis of repeated annual GDP growth of 1.8% in this and the coming two years. 2025 is upgraded on account of the better Q3 outcome, but with the 2026 projection intact compared to three months ago. This is slightly above potential, but very much below consensus for both 2026 and 2027, this partly a result of the U.S. tariffs. Moreover, that outlook still comes with downside risks which encompass a consumer recovery next year that may be very feeble. This reflecting what a clearly rising jobless rate (which has reached 9% and may stay there on average through 2026) and which should mean that wage growth this and next year may fall from last year’s 4%. Admittedly the jobs rate should start to fall back into 2027, but at present forward-looking indicators such as survey based hiring plans show no signs of any revival. All of which hinting that the tentative recovery in household disposable income could yet stall, this explaining at least partly weak consumer confidence. There is also what is already a sustained rise in household savings and also the fact that 2022-23 Riksbank tightening still seems to be biting given the continued nominal fall in bank lending which now seems to be accentuating on the company credit side.

There are some upside risks not least the impact of the easing Riksbank rates, made more forceful given the mortgage market is much more based around floating rates. Fiscally, next year’s general election has triggered even more fiscal stimulus, this also seeing a one ppt upgrade of defence plans which now envisage it rising to 3.5% by 2030. If so, any domestic bounce may precipitate a steeper than otherwise recovery in imports, implying that the growth contribution from external trade may be slightly negative in 2025 and 2026 but more neutral by 2027. This also implies that the current account surplus may be below 6% of GDP this year and fall toward 5% in 2026 and stay there in 2027. Even so, as for the fiscal outlook, a budget gap of around 1.5 % of GDP this year is poised to almost double in 2026, meaning that, the government debt ratio is now likely to rise some two ppt toward 36% of GDP next year. One medium-term question is whether the politics and the economy allow the fiscal gap to be reined in from 2027 as the recent Budget envisages. We are skeptical but pencil in a 1.5% budget gap both headline and on a structural basis for 2027!

Figure 3: Inflation Expectations Running Below Target?

Source: Prospera

As widely expected, the Riksbank kept its policy rate at a cycle low of 1.75% this month. The Board was again very clear that while no further easing is expected, rates will stay at this new lower level for some time to come. Updated projections show no earlier policy reversal and we think the Board will be reluctant to make any changes to this policy outlook in the next six months or so; this currently envisages a tightening cycle beginning into early 2027 but even then with little more than 25 bp hike though into 2028. Regardless, we do not see any looming policy reversal, as we see this projected rate cut staying in place into and throughout 2027, underpinned by low inflation and modest real growth.

Switzerland: Less Punitive But Still Punishing Tariffs?

A collective sigh of relief was almost audible now that the U.S. has agreed that the 39% tariff will be cut back to the 15% level that most of its European neighbors (and competitors) face. This will include the same rate on pharmaceuticals, vital as they account for 40% of Swiss exports. Indeed, the tariff reduction importance can be gleaned by the simple statistic that the Swiss economy is very exposed to global trade with overall exports representing some 68% of GDP and goods exports alone some 48% and where some 2%-plus of Swiss GDP comes from exports to the U.S. An output reversal in pharmaceuticals was behind the shock 0.5% Q3 GDP contraction, an outcome that is very much consistent with our semi-consensus and below-trend GDP existing outlook of 1.2% growth this year and where momentum is very much lacking (Figure 4). But given global uncertainties and relative weakness in nearby trading partners, we have downgraded the 2026 outlook a couple of notches to 1.0%, but which would have been more negative were it not for the likely boost from sporting events (FIFA World cup and Winter Olympics are likely to boost headline GDP by over 0.3 ppt). In other words, sports adjusted GDP growth next year may be below 1% and thus some 0.5 ppt below potential. The result will be a further rise in the jobless rate to over 3% next year. Even so, so, this means that the 1.2% penciled in for 2027 is actually somewhat firmer on an underlying basis, given the lack of sporting event in 2027.

It is also possible that the tariff threat is making banks wary about lending, this possibly explaining continued weakness in private sector credit, especially outside of mortgages. But the tariff threat also poses a clear disinflationary risk both from somewhat more subdued demand but also from displaced exports (mainly from Asia) that would have gone to the U.S. For Switzerland, this will merely add to disinflation pressures increasingly evident at home. To many, the strong Swiss Franc poses the clearest such disinflation pressure, but this is only partly responsible for imported consumer goods inflation now running below -2% y/y. But this masks even clearer domestic disinflation of late with adjusted m/m data suggesting that it now running at just above zero, actually softer than the main core CPI measure. This therefore means that the SNB faces a triple disinflation threat; from abroad via tariffs and the exchange rate but also now and increasingly at home. Admittedly, the SNB’s inflation target offers flexibility in that it merely stipulates inflation below 2%, but any prospect of persistent negative headline inflation is not one the SNB will take lightly. This is one reason behind out marked downgrade to our 2026 CPI outlook, down 0.3 ppt to 0.3% and with downside risks to the 0.8% rate forecast for 2027!

But far from boosting consumer thinking, weak inflation and the worsening labor market are still weighing on household sentiment, reflecting continued worried about family finances, in turn, hurting spending plans. The question is whether this is a vicious circle in which inhibited consumers are becoming more and more price resistant. This price resistance may mean that solid 1.7% consumer spending backdrop of last year may slow meaningfully in 2025 and not improve until 2027. As for overall GDP, there also has to be a recognition of the soft backdrop we see in the Eurozone, as well as Switzerland not escaping U.S. tariffs. But also on the flip side into 2026, the extent to which the now likely German infrastructure and EU-wide defense initiatives spill over into Switzerland. This may be accentuated by construction staging a clearer recovery amid increasing evidence that the real estate market has passed the worst. Regardless, into 2025, these developments may help keep the current account surplus into 2027 around the circa-5.5% of GDP outcome we expect for this year.

Figure 4: Only Modest Real Activity Momentum

Source: SECO

As for the policy outlook, the SNB kept its policy rate at zero this month, as widely expected, with little shift in the forecast for either growth or inflation. Overall the SNB sees medium-term inflation within the confines of its target range of less than 2%, this was and will be enough to justify stable policy. We still see policy remaining on hold until at least mid-2027, with only a slight possibility of a return to sub-zero rates given the high(er) bar seen by the SNB for this to occur.

The strong Franc, more recently against the USD, is also unlikely to have had any policy impact. While still pointing to possible FX intervention and a continued willingness to adjust policy accordingly, the SNB was keen to suggest its currency aspirations and actions are not designed to boost Swiss competiveness. But this seems more talk than action as any overt attempt to weaken the currency via intervention or lower/negative rates may be shunned by the SNB for fear it would court U.S criticism and possibly fresh tariff retaliation.

Norway: Economy More Fragile

For some time, we have argued that Norway’s fixation with apparently resilient inflation was overdone, resulting in overly cautious policy-making, the latter also fixated by the exchange rate. We now highlight (Figure 1) signs that inflation has been well behaved and largely in line with the 2% target once both food and energy are excluded, as opposed to the targeted measure of CPI-ATE which just excludes some energy products. This soft recent trajectory explains our the weaker-than-expected outlook we have for inflation. With this in mind we are content that, after a food -related 0.1 ppt upgrade to the 2025 inflation picture, we make little change to 2026 outlook, it being also upgraded only a notch to 2.2%, but where sub-target outcomes could be seen through parts of next year and 2.0% for 2027.

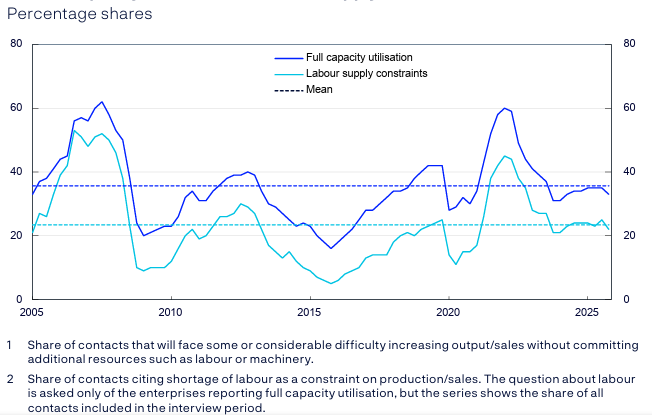

The economy (both real and nominal) has been strong in the H1 2025 but there are now signs of a slowing having occurred and from an array of alternative sources. Not only did Q3 GDP growth slow to a crawl, but actually reflected marked weakness at the end of the quarter, which suggest more persistent fading momentum. This is backed up by other data, not least slowing corporate credit growth, which may be a victim of tight monetary policy (see below). But, as we highlighted three months ago, the strength before Q3 came alongside some signs of a possible stronger potential growth backdrop. This was hinted at by both seemingly better productivity data and a further rise in participation (which has seen a circa-three-point rise to 73% in the last five years). We suggested last time that this implied overall capacity utilization may actually not be too far away from normal. But it now seems as if it may actually below average. According to the just-released Norges Bank's Regional Network, capacity utilization fell somewhat compared with the preceding surveys in 2025 while there is less recruitment difficulties, with both series now below their long-term average (Figure 5). This means economic slack remains enough to help underlying disinflation.

It is notable, that this disinflation is occurring against a backdrop of a still clearly restrictive monetary policy. Recently , the Norges Bank has updated its thinking regarding the real neutral rate. Its models estimate it is around 0.4%, which indicates that an assumed inflation on target would mean policy is currently very restrictive, by almost two full ppt! This is one reason why after a 0.3 ppt downgrade to the 2025 GDP picture (to 1.5%), we largely adhere to the 1.3% and below consensus 2026 projection, this partly due a more restrictive policy stance that envisaged previously. We do see a better picture emerging next year, as the q/q pattern will show a pick-up so that the end-2026 GDP is actually very much the same as the 1.5% rate now projected for 2027.

Indeed, as far as the real mainland economy is concerned, there are several factors we see restraining it into 2026. First, oil investment has peaked and this will filter through even into the mainland economy, this also likely to see the current account deficit fall from to around 15% of GDP this year – it also means that overall GDP (as opposed to mainland GDP) may grow by less than 0.5%. Secondly, the solid growth in interest-rate-sensitive sectors such as private consumption and housing investment, may have reflected what earlier in the year were widespread expectations of a succession of rate cuts that never materialized. Notably more recent data does suggest some slowdown is occurring, especially in housing. Thirdly, global trade conflicts will hit Norway even though exports to the U.S. make up only about 8% of mainland exports.

Figure 5: Capacity Utilisation and Recruitment Problems Now Below ‘Normal’

Source: Norges Bank

No change in policy and little shift in rhetoric was the message from the Norges Bank’s latest verdict this month. This was consistent with the Board’s repeated assertion that ‘the policy rate will be reduced further in the course of the coming year’. But with underlying inflation dynamics being friendly (see above) and seemingly downside economy risks materialising, we still think that the Norges Bank is being far too cautious as it plans to keep policy very restrictive through the projected timeframe out to 2028, ie the policy rate stays above 3%. We also wonder why the Board therefore sees inflation only just approaching the 2% target by the end of that period, this despite a clearer output gap envisaged.

Given Norges Bank caution, we remain a little less confident about the extent of easing into 2026 but envisage further 25 bp cuts every quarter through next year and then similarly into H1 2027. At 2.5%, that would still leave the policy rate still within the estimated neutral rate range. In other words, the Norges Bank will be merely taking its foot of the brake, rather than pressing on the accelerator.