China Big Banking System: Lessons from Japan/GFC

The proposed Yuan1trn capital injection for the six largest banks would be pre-emptive, while China is also quick to merge weaker/failing small to mid-sized banks. However, rising NPL’s; plus, low net interest margins with low policy rates; low nominal GDP and pressure to rollover LGFV/SOE debt will likely all ensure that overall lending growth is restrained in the next few years – this means an economic cost of the banking problems. Additionally, rising NPL’s/confidence concerns could cause more small and mid-sized banks to run into solvency issues and this could cause intermittent 2 tier banking stress and mini crisis in China.

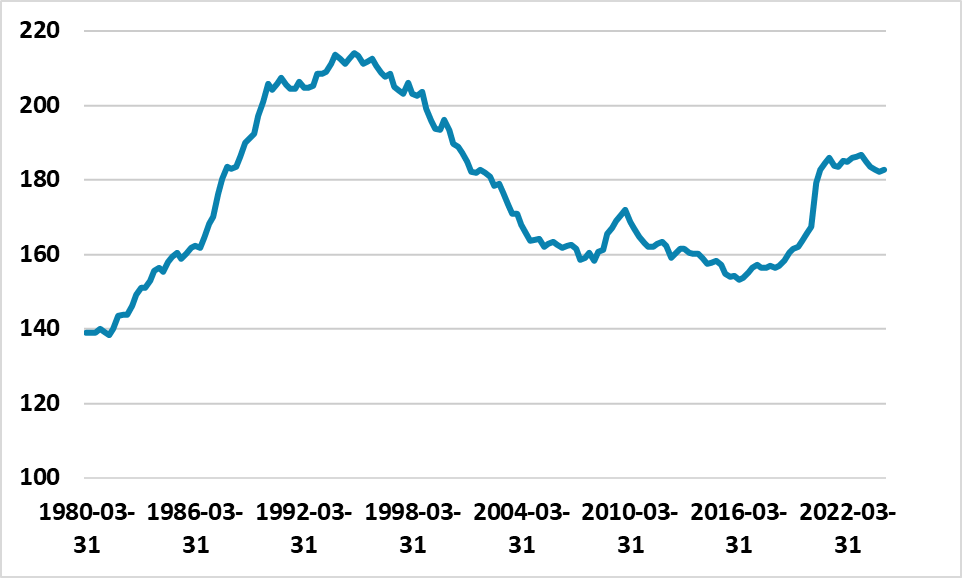

Figure 1: Japan Credit to Private Non-Financial Sector (%)

Source: BIS/Continuum Economics

Can Japan’s banking crisis experience in the 1990’s provide some lessons for China? Japan credit to non-financial institutions did not peak until 1995 (Figure 1), both as prior commitments came through and a reluctance existed to accept the shift prompted by the structural slide in land and property prices. However, by 1997 Nippon Credit Bank and some regional banks had to be rescued and then 1998 Long Term Credit Bank and a number of domestically focused banks – the latter due to depositor’s flight. The government injected Yen7trn (USD63bln) of equity capital into the system by 1999. Japanese authorities were slow to understand that the decline in property prices would cause a surge in NPL’s (7.8% of GDP by 1999), which threatened solvency of weaker banks and only react more aggressively in the 1998-99 banking crisis – see BIS review for details (here). Rating agency downgrade; squeezed net interest margins due to the fall of policy rates towards zero and deteriorating bank profitability were all warning signs.

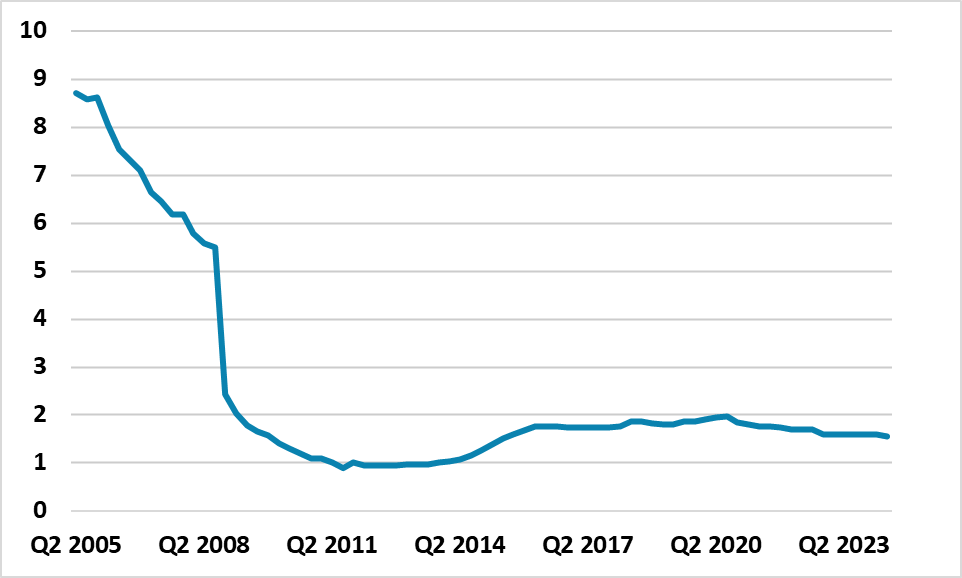

China appears to have already learnt some lessons from the Japan banking crisis 1997-99; GFC 2008-09 and of course the rescue of China major banks 1997-03. Firstly, deposit insurance of Yuan500k was introduced from 2015, to help curtail bank runs from depositors. Secondly, China forces weak banks to accept takeovers by stronger banks or a multi-bank consolidation overseen by local governments, rather than allowing any failures that could sap banking confidence. Thirdly, China’s authorities are considering injecting Yuan1trn (USD142bln) into the six biggest banks as equity capital. This is to boost lending and growth but will be at least partially counterbalanced by less lending from small and mid-sized banks. It could also be a preemptive move to strengthen balance sheets for the coming challenging years when net interest margins get squeezed further and the lagged effects of the residential property crisis prompts a rise in NPL’s (Figure 3). Even so, a number of major issues exist.

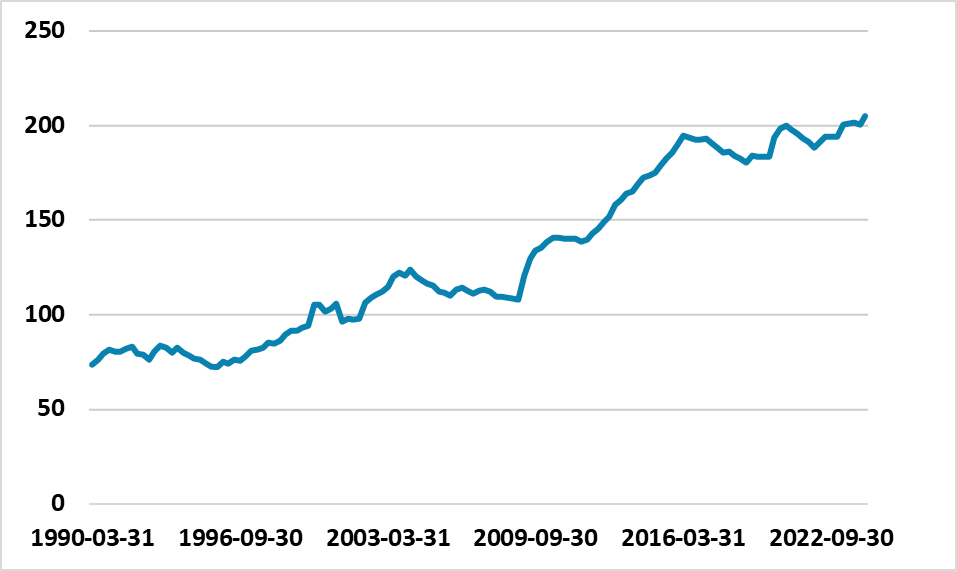

Figure 2: China Credit to Private Non-Financial Sector (%)

Source: BIS/Continuum Economics

Figure 3: China NPL Ratio to Total Assets (%)

Source: Datastream/Continuum Economics

Source: Datastream/Continuum Economics

· High credit-GDP of banking system. Figure 2 shows that credit to households and corporates is over 200% of GDP and close to the peak seen in Japan in 1995 (Figure 1). The PBOC financial stability report for 2023 (here), shows the total banking system’s asset and liabilities are huge at Yuan379trn (USD53.6trn). This reflects decades of high loan growth, which at first went to productive investment but in the last decade has gone into the post 2008 spurt in the economy. A lot of the corporate loans are however to LGFV’s, central and local SOE’s (here) and these are unlikely to be allowed to default but rather will be extended or in the case of LGFV shifted to the government balance sheet via debt swaps. With nominal GDP now low by China standards at around 5%, this means that banks could be cautious about new loans, especially to the private sector. M2 and total social financial growth are showing signs of weak credit demand and curtailed credit supply.

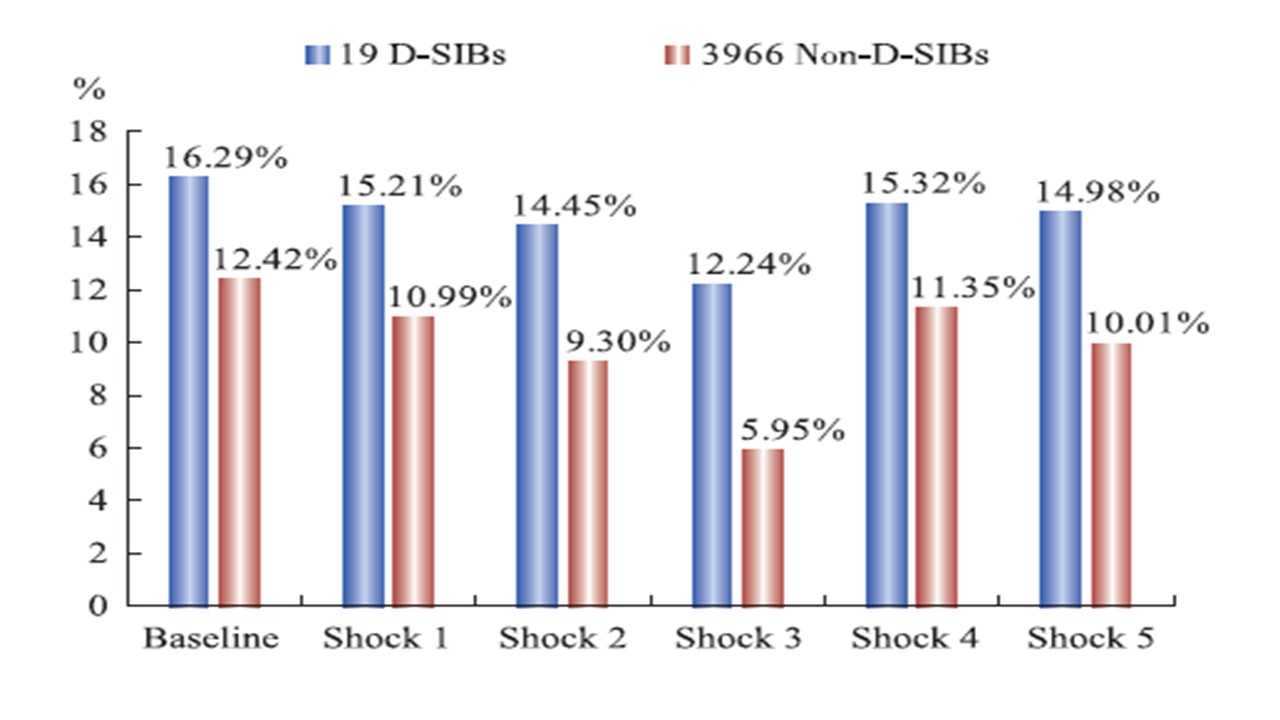

· Rural bank problem in stress tests. The largest banks are better capitalized and the 2023 PBOC financial stability report shows that the weakest link is some rural banks. The good news is that China’s 19 major domestically systemically important banks (D-SIB’s and 72% of loans) hold up well under most solvency and liquidity tests, though some capital shortfalls start to appear with a moderate or severe NPL sensitivity shock scenario – this is perhaps on extra reason why the government has been pre-emptive in considering injecting equity capital this month. However, small and mid-sized banks shortfall of capital in the more severe sensitivity scenarios (Figure 4) would test China authorities crisis management and response capacity that could mean a lower tier bank crisis is not quick to be resolved. Shock 2 (NPL’s up 200%) sees a huge 2020 banks fall below 12% capital ratio and 2605 banks on shock 3 (NPL’s up 400%).

The proposed Yuan1trn capital injection for the six largest banks would be pre-emptive, while China is also quick to merger weaker/failing small to mid-sized banks. However, rising NPL’s; plus, low net interest margins with low policy rates; low nominal GDP and pressure to rollover LGFV/SOE debt will likely all ensure that overall lending growth is restrained in the next few years – this means an economic cost of the banking problems. Additionally, rising NPL’s/confidence concerns could cause more small and mid-sized banks to run into solvency issues and this could cause intermittent 2 tier banking stress and mini crisis in China.

Figure 4: PBOC Solvency Stress Tests

Source: PBOC