China: The Squeezed Middle and Bottom 50%

Uncertainty over income and employment, adverse wealth effects from lower house prices, plus growing risk aversion, will likely mean that consumption continues to struggle. This is one of the key reasons why we forecast slower H2 GDP growth and look for 4% in 2025.

Sluggish China retail sales/negative auto sales and price cuts for luxury goods suggest that China consumption is struggling. What are the causes?

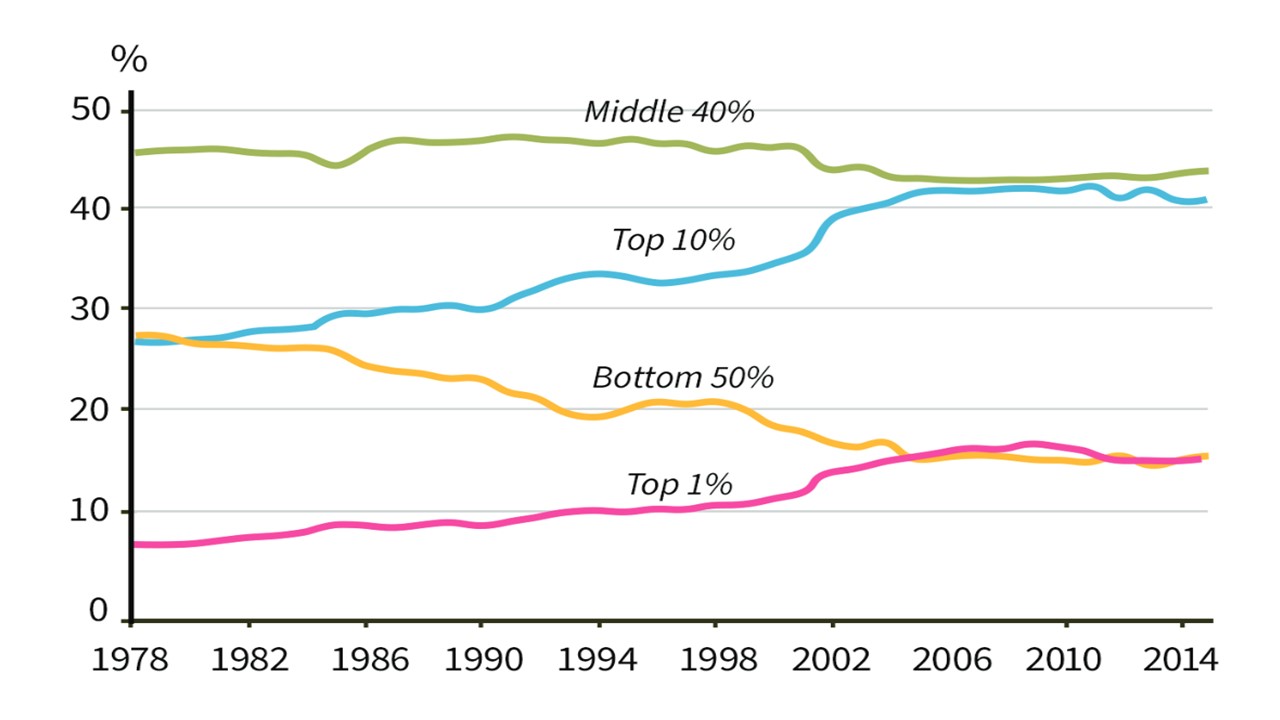

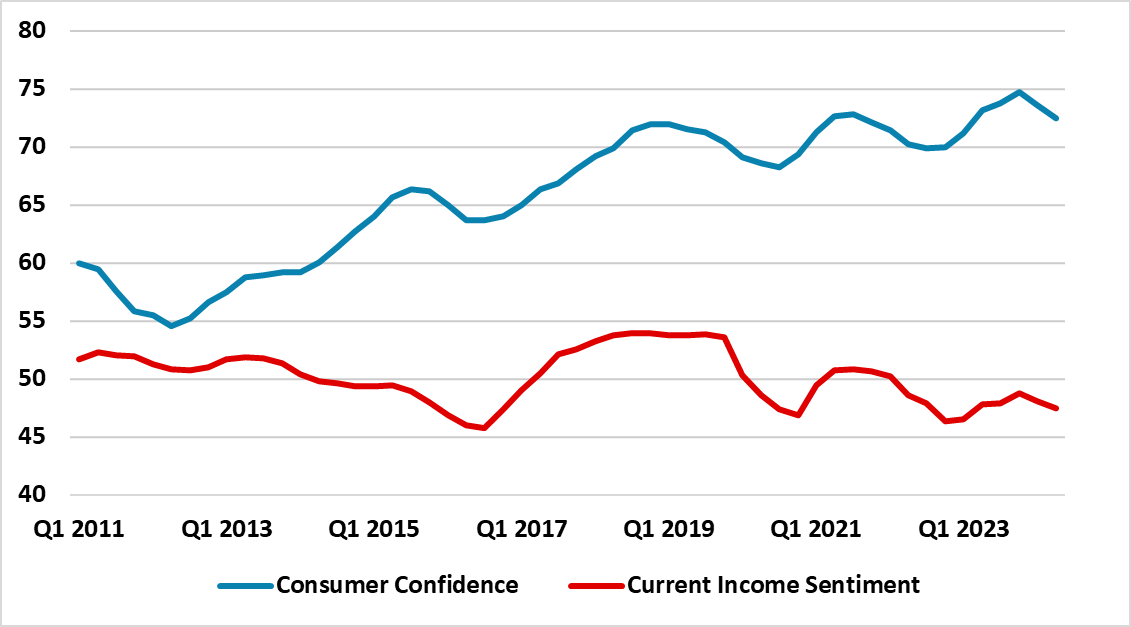

Figure 1: China Consumer Confidence (Index) and Sentiment Towards Current Income (Diffusion Index (4 quarter MA)

Source Datastream/Continuum Economics

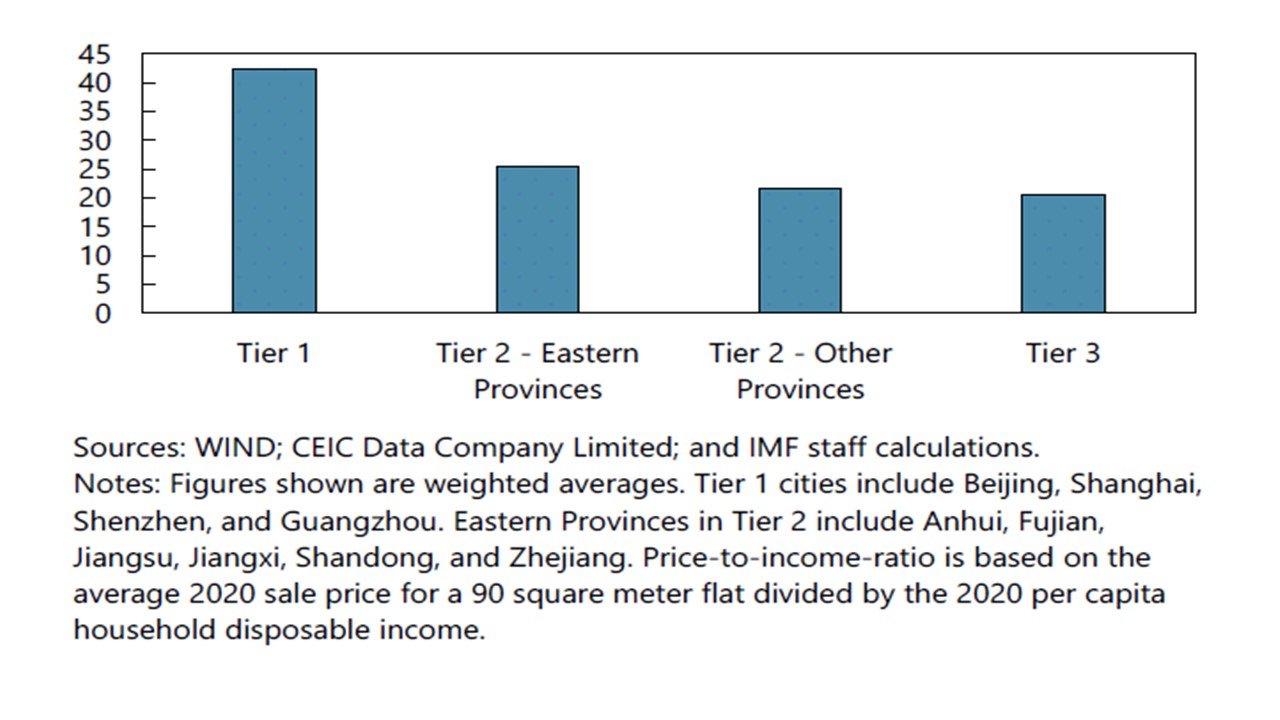

China’s monthly retail sales data show a clearly struggling consumer, due to a number of factors. Firstly, uncertainty about employment - and hence income - has risen over the past few years. Though overall consumer confidence has held up quite well, current income sentiment is soft (Figure 1). China private sector companies hired a lot of people prior to 2020, but this has slowed in recent years partially due to a less business friendly outlook with a crackdown on various sectors (e.g. technology and education). Secondly, COVID stopped the rural to urban migration flow, which slowed the jump in income and consumption for migrating workers. This has resumed, but some lingering hesitancy exists. Thirdly, China households are suffering adverse wealth effects, due to lower house prices. Though China’s household wealth and income have surged in the past three decades, this has benefitted the top 10% disproportionately. For income they account for 40% of total household income (Figure 2) and the top 10 have 67% of total wealth, according to the Stanford center on China’s economy – wealth estimates are a complex business using China’s data and come with a considerable lag. Lower wage and GDP growth now means that the middle and bottom 50% are starting to get squeezed.

Figure 2: Trends in Income Inequality (Yr/Yr %)

Source Stanford Center on China’s Economy (here)

China’s households have been used to persistent rises in house prices over the few decades up to 2021, while culturally housing as an investment is prized in China. However, the sentiment in the property sector is awful, with an excess of new homes pushing down prices for new homes and causing low expectations of house price increases (Figure 3) meaning that house prices are still falling. The official house price data for new and existing house prices has also been questioned, as anecdotal evidence from estate agencies points to more noticeable decline in prices. China households could thus be starting to feel adverse wealth effects from falling house prices. Estimates of up to 70% of China household wealth in property is much higher than the U.S. where property is 27% of gross assets (here). Other assets do not compensate with China’s equity market also in the doldrums and a clear increase in low earning deposits by household. This is all adding to a growing sense of risk aversion and flight to safety, which is showing through in high demand for government bonds despite the authorities’ protests.

Figure 3: Monthly New House Price Change (%) and Expectation of House Price Increase Next Quarter (Index)

Source Datastream/Continuum Economics

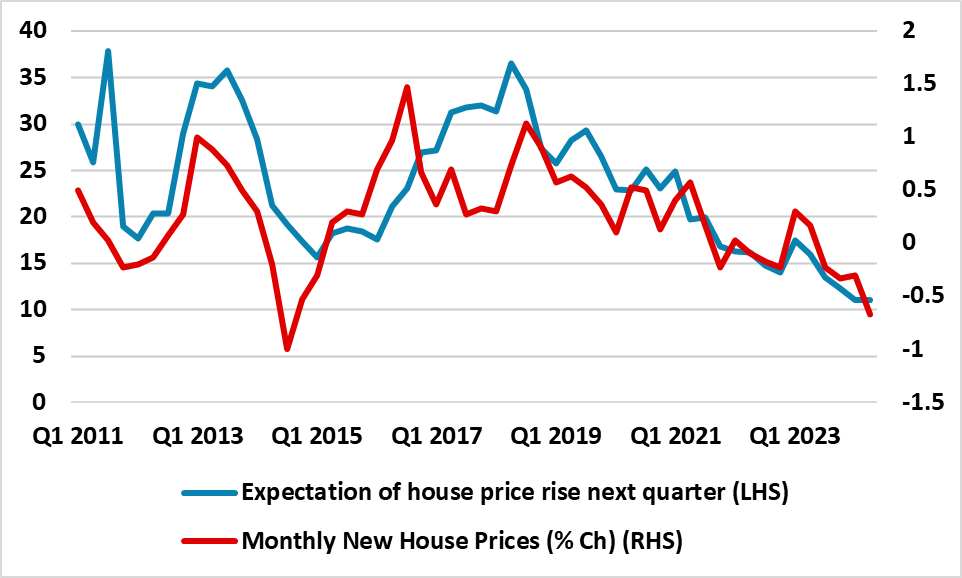

House price declines have also been restrained by the authorities, but this could end up prolonging the price adjustment. It also does not help that house price to income ratios were excessive in 2020 (Figure 4). While China’s housing market is different in some ways, overvaluation suggests that real house prices still need to fall a lot further given the experience in U.S./Spain 2006-2010 and UK/Scandis in the early 1990’s. Additionally, ultra-low CPI inflation means that a decline in real house prices to establish a bottom requires mainly nominal house price declines! For most households this means less positive wealth in housing given deposit requirements, rather than a wholesale shift to negative equity in houses as deposits of 30% were usual. Even so, perceived adverse wealth effects for China’s consumers will likely grow. Additionally, this will make households reluctant to buy properties, until the market has reached a bottom or a major game changer is seen.

Figure 4: House Price to Income Ratio 2020 (Multiples of Per Capita Household Income)

What will policymakers do? China’s authorities have not placed households too high on the list for targeted action with a focus on infrastructure spending, housing construction support measures and boosting high tech manufacturing. The focus is more output than consumption. However, overall debt levels leave the authorities reluctant to consider a game changer e.g. Yuan 2-4trn package to buy excess new homes inventory. Last week’s 3 plenum appears to have produced no major policy actions and a bias to targeted support for output rather than consumption. Structurally, China’s households need better government led safety nets for education/unemployment/health and pensions, which would reduce precautionary savings and structurally boost trend consumption growth. For now, the prospect is that uncertainty over income and employment, plus adverse wealth effects, will likely mean that consumption struggles. This is one of the key reasons why we forecast slower H2 GDP growth and look for 4% in 2025.