Western Europe Outlook: Policy Divergences

· In the UK, we have upgraded 2025 growth by 0.2 ppt back to 1.0%, but pared back that for next year by a notch to a sub-par 0.8%. We think this will refresh somewhat stalled disinflation allowing the BoE to ease further into H1 by around 75 bp.

· Sweden has seen a clear easing in both its monetary and fiscal policy stances, but the growth outlook still seems weak for now and where the Riksbank’s activity optimism still looks overdone. Even so, we are forecasting a growth pick-up in 2026, which should see the Riksbank holding rates.

· In Switzerland, the tariff impact may be sizeable affecting both growth and adding to disinflation, although where the latter may avoid turning negative. Even so, the SNB is most likely done, easing wise unless (in the unlikely event) already soft inflation turns more negative.

· In Norway, while the economy (both real and nominal) has been strong so far this year, the strength also comes alongside some signs of a possible stronger potential growth backdrop, something we think makes the Norges Bank’s caution about stubborn inflation overdone.

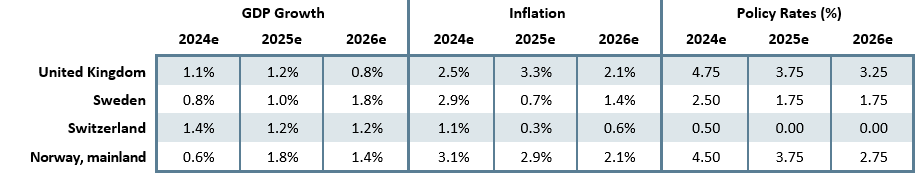

Forecast changes: Compared to our June Outlook, 2025 growth forecasts have been largely upgraded due to a firm Q1, with Switzerland the notable exception. Some would suggest that, surprisingly, this better 2025 backdrop comes with downward CPI revisions except for the UK and Norway, but with little alteration to the respective policy outlooks. Indeed, we still suggest a durable return to (or below) for all central bank inflation targets into next year so that our policy outlook is little changed save for Norway, with a 25 bp rate upgrade for end-2026!

Our Forecasts

Source: Continuum Economics

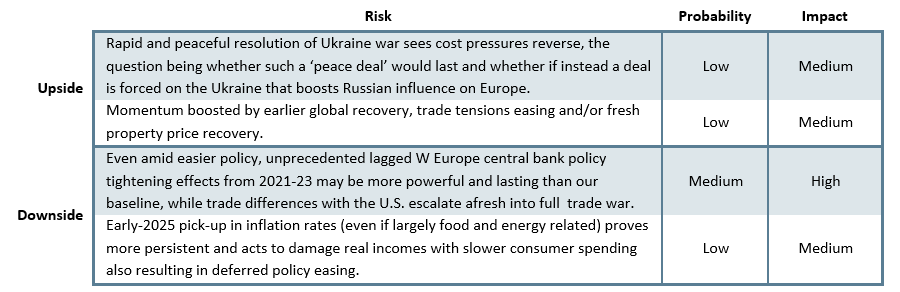

Risks to Our Views

Source: Continuum Economics

Some Leaving the Easing Party?

Monetary easing has proceeded at very different levels and speeds across the four W European central banks, the Norges Bank being the notable latecomer, so late in fact that the Riksbank and SNB may already have left the room by now (very probably) ending their respective rate cut cycles. Meanwhile, although its quantitative tightening program has been scaled back, the BoE is still the only major central bank that is also pursuing outright sales of its bond portfolio but is very keen to stress the separation of conventional and unconventional policies and to emphasize that its is Bank Rate that is the active policy tool when adjusting the stance of monetary policy. However, the BoE may be considering at least pausing what has so far been a gradual easing cycle, just as the UK government may be about to tighten fiscally, a contrast to what is seen in budget terms elsewhere in W Europe.

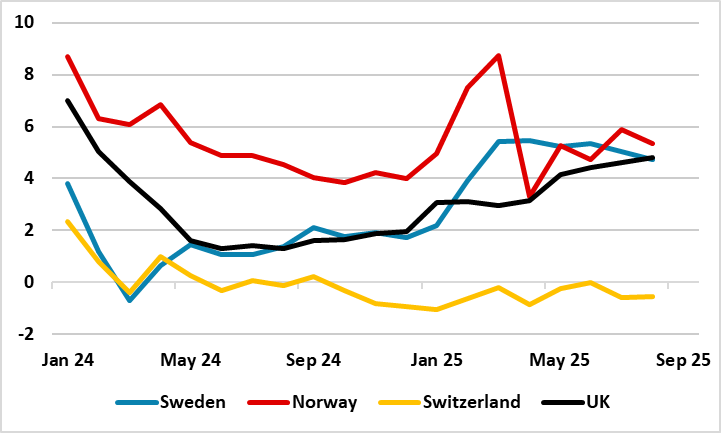

This is partly a result of what has been a rise in UK inflation based around regulated, food and energy prices. In this regard, the UK has not been alone, with food price inflation also evident in both Sweden and Norway so far this year, seemingly more weather driven than by demand. Notably this is creating what may be very favorable base effects for a sharp fall in CPI inflation in H1 next year. Switzerland remains the notable exception (Figure 1), where core adjusted m/m numbers have dropped towards a zero trend of late and where underlying numbers are consistent with target for both Norway and Sweden. This inflation divergence has little to do with deviating growth backdrops, where so far growth has largely surprised on the upside.

Figure 1: Prices – Food for Thought

Source: CE, consumer food prices, % chg y/y

UK: The Fiscal Elephant in the Room?

Even more than in the last few Outlooks, the forecasts that we are updating here are tinged with uncertainties. The forecasts are little changed compared to three months ago; that for 2025 upgraded 0.2 ppt to 1.2% largely due to a better Q2 outcome, but partly offset by a notch downgrade for next year to a below-par and below consensus 0.8%. Notably, the latter masks a gradual q/q improvement through the year so that end-2026 growth is just over 1%, albeit still down a little on the likely end-2025 projections. But the uncertainties are high and twofold. Firstly, given diverging and conflicting data, we remain unsure as to the current state let alone how activity may pan out. Apart from well-known and protracted problems in assessing the labor market, this divergence is very much highlighted by PMI survey data painting a more upbeat picture to clearly sobering numbers from the CBI – the latter notably covering a much greater sector spread of the economy. Moreover, softer survey data chime with increasing weakness regarding private sector employment and where government borrowing is exceeding forecasts. The weaker 2026 picture reflects several factors, not least that lagged monetary policy effects (both conventional and unconventional) may be biting harder than at least the BoE has factored in. Indeed, policy is still biting the economy through the credit channel, where weaker signs are already re-emerging as highlighted by fresh news of an ailing housing market.

But, over and beyond what are likely to be persistent trade worries and uncertainties, the main factor is of course the growing evidence that the tax rises and added government borrowing has damaged economic sentiment and curtailed, if not reversed, hiring. Indeed, the risk is growing that the fiscal update (due Nov 26) will see more tax hikes/spending cuts to add to the welfare bill reduction already flagged; a sizeable further fiscal reversal may be needed to provide a credible repair to ensure the fiscal rules, maybe as much as almost 2% of GDP by 2030 this all the more notable given the extent to which the public sector has supported growth of late (a fair portion of the fiscal tightening may come towards the end of that period). Admittedly those rules could yet be diluted, the question being whether this would be counter-productive as an adverse gilt market reaction to a budget deficit staying above 4% would compromise the falling debt rule and may merely lead to a further tightening in financial conditions.

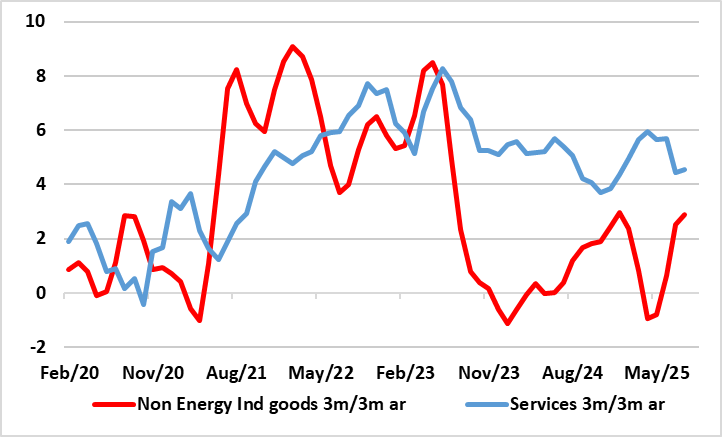

Another factor hampering growth is the fresh pick-up in inflation. We note that recent CPI resilience has come more from food and energy than services (Figure 2). This is important as a) it is not indicative of demand and b) with both such goods being non-discretionary they are likely to cramp spending power even more, especially on more discretionary spending, this including a wide range of services.

All of which to us means that this year consumer spending may not pick-up much from the 0.6% growth set last year. Meanwhile, an added headwind is provided by a weaker overall European growth backdrop, most notably for the EZ although this may be more short-lived that previously envisaged given the fiscal and defense initiative the EU is trying to put together. Regardless, we see imports recovering (further) which, together with the fragile export picture, points to a wider current account deficit than that seen in 2024 (ie around 2.75% of GDP) in 2025.

This below-par growth outlook into and through 2026, should refresh the disinflation signs seen of late which we suggest hitherto have been a more a result of an easing in supply pressures. As a result, inflation may now average around 3.3% in 2025, 0.1 ppt higher than previously thought. Regardless, we still see a 2026 outlook with a similarly changed 2.1% projection. Underscoring this is our view that the labor market is both weak and still loosening far faster than the gradual manner explicit in BoE thinking.

Figure 2: Inflation Persistence Is Goods Not Services Related

Source, ONS, CE, % chg

As for the BoE, that Bank Rate stayed at 4% after this month’s MPC meeting was all but certain, as was the two vote dissent in favor of further easing. But of more note, and after what have now been five cuts in the current cycle was that the MPC adhered to its (conventional) policy guidance. It still suggests that a gradual and careful approach to the further withdrawal of monetary policy restraint remains appropriate and that policy is not on a pre-set path, but will instead respond to the accumulation of evidence. As for how that evidence may develop, we think that the MPC majority has a clear degree of complacency regarding what we think is a rapidly (not gradually) deteriorating labor market (see above). While the BoE may wish to assess the fiscal outlook better before moving afresh, thus therefore ruling out the next move before December, we think that how labor market data will continue to develop poorly warrants the further circa-75 bp of rate cuts we have penciled in into H1 next year. That would still Bank Rate in what we would suggest restrictive territory once wider financial conditions are penciled in, though some on the MPC would argue that this is neutral policy rates in narrow level terms.

Sweden: Easing Cycle Ending as Fiscal Policy Takes Over?

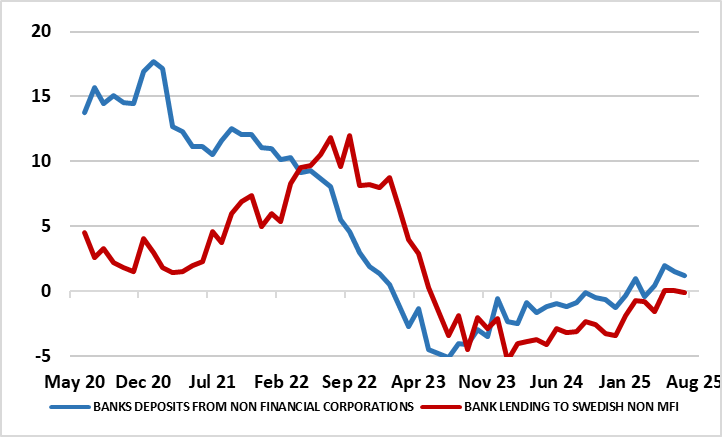

Another weak quarter in Q2 has helped pull consensus thinking regarding 2025 GDP growth down toward out little changed 1.0% estimate. We also remain below consensus thinking regarding next year where we retain a view of a moderate pick-up to 1.8% next year, this below-par projection only partly a result of the U.S. tariffs. Moreover, that outlook still comes with downside risks which encompass a consumer recovery next year that may be very feeble reflecting a clearly rising jobless rate which may even approach 9% into 2026 and which should mean that wage growth this and next year may fall from last year’s 4%. Indeed, forward-looking indicators such as survey based hiring plans show no signs of any revival, all hinting that the tentative recovery in household disposable income could yet stall, this explaining at least partly weak consumer confidence. There is also what is already a sustained rise in household savings and also the fact that 2022-23 Riksbank tightening still seems to be biting given the continued nominal fall in bank lending (Figure 3). Indeed, we think that the latter is a reflection of Riksbank policy also biting unconventionally as its balance sheet reduction, via its impact on bank deposits, is still affecting banks willingness/ability to lend – the hope is that this may reverse given the Board’s plans to stop bond sales by year-end.

There are some upside risks as next year’s general election has triggered even more fiscal stimulus, this also seeing a one ppt upgrade of defence plans which now envisage it rising to 3.5% by 2030. If so, any domestic bounce may precipitate a steeper than otherwise recovery in imports, implying that the growth contribution from external trade may be slightly negative in 2025 and 2026. This also implies that the current account surplus may be well below 7% of GDP this year and in 2026 fall toward 5%. Even so, as for the fiscal outlook, a budget gap of around 1.5 % of GDP this year is poised to double in 2026, meaning that, the government debt ratio is now likely to rise some two ppt toward 36% of GDP next year, the question being whether the politics and the economy allow the fiscal gap to be reined in from 2027 as the recent Budget envisages.

Otherwise, there is the likelihood that housing construction (which has already fallen steeply due to lower house prices, higher construction costs and expensive financing) continues to contract into next year with an added negative now emerging in terms of much softer population growth. All of which could mean an output gap of possibly over 2% at present but one that should not get larger as our outlook for next year is actually we see near-trend growth.

This is only likely to reinforce the disinflation process, still evident and where despite some recent upside surprises, to us, the underlying picture is reassuring as seen in the official ex-energy measures still consistent with target and this is despite the impact on this measure of food inflation now running at over 5%. But the recent upside surprises earlier this year have created a marked base effect and hence why we, alongside the Riksbank, see inflation on this basis slumping back in early 2026, with CPI weakness likely to be accentuated by what is now a scheduled VAT cut in April 2026, which should have an immediate (but temporary) impact in slashing over 0.5 ppt off all main inflation measures. Thus we have reduced our 2026 CPI projection from 1.8% down to 1.4% and we see targeted inflation (CPIF) moving and then staying below 2% through 2026 although the mortgage rate induced base effects will pull it higher next year. Regardless, this picture is now being acknowledged: inflation expectations measures are back at or below target and pre-pandemic averages.

Figure 3: Private Credit Growth Weakness Due to Soft Deposits Base?

Source: Stats Sweden (% chg y/y)

As widely expected, the Riksbank cut its policy rate by a further 25 bp to a new cycle low of 1.75% this month. The Board was very clear that no further easing is expected but that rates will stay at this new lower level for some time to come – the projections show a lower rate profile but a slightly earlier policy reversal. The rationale was clear; the Board accepted that growth and now the labor market have been weak for a long time and any recovery may arrive later, so there was a need to support to the recovery and to stabilize inflation We go along with such Riksbank thinking although it may have to revise any suggestion that the hefty tax cuts dished out into 2027 as the recent Budget envisages will have no inflationary consequences. Regardless, we do not see any looming policy reversal, as we see this projected rate cut staying in place into 2027.

Switzerland: Punishing Punitive Tariffs?

How punitive will be the 39% tariff the U.S. still intends to impose on Switzerland can be gleaned by the simple statistic that the Swiss economy is very exposed to global trade with exports representing some 68% of GDP and goods exports alone some 48% and where some 2%-plus of Swiss GDP comes from exports to the U.S. But the risks are greater given that (as yet) pharmaceuticals are not included but the industry is concerned by the outcome of the U.S. Section 232 national security investigation into the sector. This could result in tariffs on drug imports eventually reaching 250%, although a much smaller outcome is more likely but with threats of higher rates ahead still. The latter sector represents some 7% of Swiss GDP (ie a larger share than the infamous financial sector) and where the bulk of pharmaceutical exports are to the U.S. Even so, we feel at this juncture that our semi-consensus and below-trend GDP outlook of 1.2% growth this year and next (the 2026 outlook revised a notch lower but would have been more negative has it not been for a reassessment of sporting events which may boost headline GDP by over 0.3 ppt next year) – in other words sports adjusted GDP growth next year may be below 1% and some 0.5 ppt below potential.

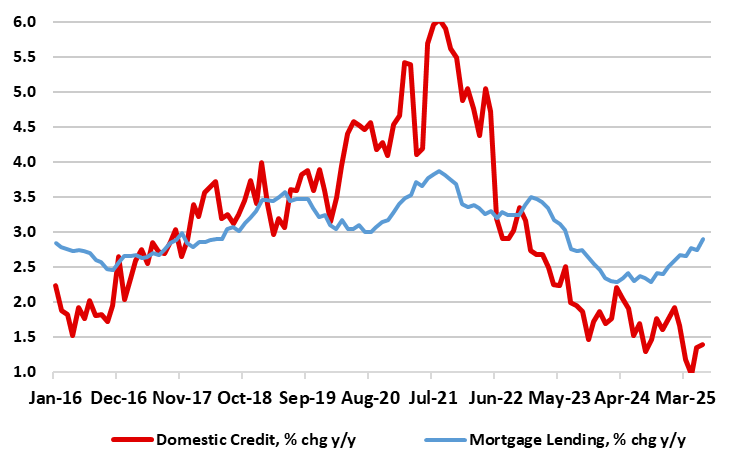

It is also possible that the tariff threat is making banks wary about lending, this possibly explaining continued weakness in private sector credit, especially outside of mortgages (Figure 4). But the tariff threat also poses a clear disinflationary risk both from somewhat more subdued demand but also from displaced exports (mainly from Asia) that would have gone to the U.S. And for Switzerland, this will merely add to disinflation pressures increasingly evident at home. To many, the strong Franc poses the clearest such disinflation pressure, but this is only partly responsible for imported consumer goods inflation now running below -2% y/y. But this masks even clearer domestic disinflation of late with adjusted m/m data suggesting that it now running at around zero, actually softer than the main core CPI measure. This therefore means that the SNB faces a triple disinflation threat ahead; from abroad via tariffs and the exchange rates but also now and increasingly at home. Admittedly, the SNB’s inflation target offers flexibility in that it merely stipulates inflation below 2%, but the prospect of persistent negative headline inflation is not one the SNB will take lightly. This is one reason behind out marked downgrade to our 2026 CPI outlook, almost halving it to 0.6%!

But far from boosting consumer thinking, weak inflation is still weighing on household sentiment, reflecting continued worried about family finances, in turn, prejudicing spending plans. The question is whether this is a vicious circle in which inhibited consumers are becoming more and more price resistant, and where the latter may mean that solid 1.7% consumer spending backdrop of last year may slow meaningfully in 2025 and not improve into 2026. As for overall GDP, there also has to be a recognition of the soft backdrop we see in the Eurozone, as well as Switzerland not escaping U.S. tariffs. But also on the flip side into 2026, the extent to which the now likely German infrastructure and EU-wide defense initiatives spill over into Switzerland. This may be accentuated by construction staging clearer recovery amid some signs that the real estate market has passed the worst. Regardless, into 2025, these developments may help keep the current account surplus into 2026 around the circa-5.5% of GDP outcome we expect for this year.

Figure 4: Weak Credit Growth a Sign of Bank Caution?

Source: SNB

As for the policy outlook, the SNB cut the policy rate by 25 bp to zero in June, as widely expected, we see no further change for the time being. Indeed, there have been clear hints from the SNB Board itself suggesting that there is now a high bar for any return to negative borrowing costs because of the adverse impact on savers and pension funds, also warning that doing so may need stronger countermeasures later on.

Admittedly, the updated inflation forecast from the looming quarterly assessment may add to clearly weak if not disinflationary price pressures, albeit where the SNB target being a less explicit sub-2% offers policy makers more flexibility. The SNB will also hope that the any threat of negative rates implicit in its inflation projections as well as the effective 'stealth' negative rate (as sight deposits held at the SNB will be remunerated at the SNB policy rate only up to a certain threshold) may help restrain the CHF strength and perhaps also encourage banks to lend. But we still see rates staying at zero through to at least end-2026

Norway: Economy Surprises on both Supply and Demand Side?

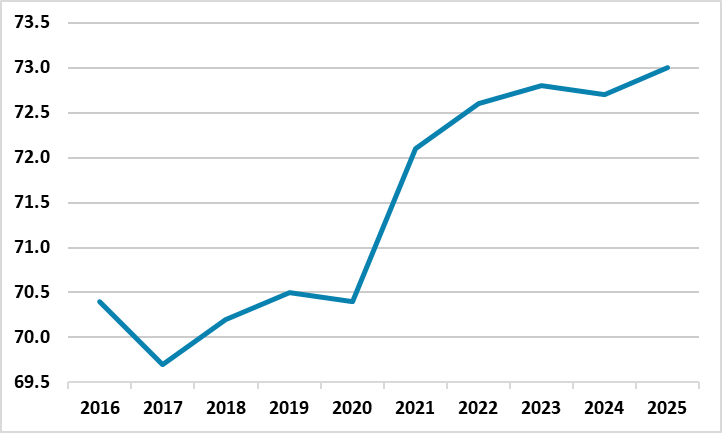

The economy (both real and nominal) has been strong so far this year. Admittedly the cumulative jump in GDP of around 1.8% does reflect a few volatile factors, namely swings in fisheries and power supply as well as easier fiscal policy. But the strength also comes alongside some signs of a possible stronger potential growth backdrop, this hinted at by both seemingly better productivity data and a further rise in participation (Figure 5), meaning that overall capacity utilization may actually not be too far away from normal. As notable, is the fact that this is occurring against a backdrop of a still clearly restrictive monetary policy. Recently , the Norges Bank has updated its thinking regarding the neutral rate. While far from a fully-fledged indicator of overall financial conditions, its models estimate that the while neutral rate has risen above zero, the average estimate current estimate is around 0.4%, which indicates that an assumed inflation on target backdrop would mean policy is currently very restrictive, by almost two full ppt! This is one reason why after a clear 0.4 ppt upgrade to the 2025 GDP picture (to 1.4%), we adhere to the 1.4% and below consensus 2026 projection, this partly due a more restrictive policy stance that envisaged previously.

Indeed, as far as the real mainland economy is concerned, there are several factors we see restraining it into 2026. First, oil investment has peaked and this will filter through even into the mainland economy, this also likely to see the current account deficit fall from to around 15% of GDP this year – it also means that overall GDP (as opposed to mainland GDP) may grow by less than 0.5%. Secondly, in what has been solid growth in interest-rate-sensitive sectors such as private consumption and housing investment this may have reflected what earlier in the year were widespread expectations of a succession of rate cuts that never materialized. Notably more recent data does suggest some reversal is occurring, especially in housing – the question being whether the further Norges Bank cut this month revives activity. Thirdly, global trade conflicts will hit Norway even though exports to the U.S. make up only about 8% of mainland exports, but where the indirect effects may be more pronounced, of course.

Despite hints of better underlying growth, CPI inflation is showing some persistence, probably a result of wage pressures affecting services in particular. Indeed, within targeted (CPI-ATE) inflation, stubborn services are partly offsetting ever softer goods and imported inflation, the latter coming in spite of the weak Krona backdrop that continues to influence Board thinking excessively. Indeed, August data shows that targeted inflation (CPI-ATE) staying at 3.1% chiming with Norges Bank thinking, the details shows core inflation running at rates more consistent with the 2% target on an adjusted and smoothed m/m basis. With this in mind we are content that after food as well as services related upgrade to the 2025 inflation picture, we make little change to 2026 outlook, it being upgraded only a notch to 2.1%, but where sub-target outcome could be seen through parts of next year. In this regard, rent increases are slowing due to lower inflation, and increased activity in the secondary housing market. NB; CPI inflation has been being bolstered by 4%-plus annual rental increases (19% of the CPI) which we think are policy pro-cyclical.

Supporting this disinflation story, the improved productivity picture makes it more likely that an output gap may already have appeared and one that could enlarge through 2025 and persist in 2026 – this view conflicting with Norges Bank thinking. But in contrast to what we think is optimistic consensus thinking on household spending, we do not see any faster growth than in 2024 and only modest growth next year broadly chiming with GDP. This is especially as, and as suggested above, the recent rise in house prices is fragile and unemployment is starting to rise although the jobless rate may just exceed 4% in 2025 and then stay there through 2026.

Figure 5: Labour Participation Rate Rising Afresh

Source: Stats Norway

Despite the stronger than expected data seen of late (real and price-wise), the Norges Bank cut is policy rate by a further 25 bp to 4.0% this month. But with a small cumulative upgrade to the real economy outlook and an ensuing reduction in the anticipated scale of an output gap, the Board pared back its projection for the policy rate in the coming years, albeit still flagging a third move for later this year. We think that the Norges Bank is being too cautious and that (on the basis of its own calculations), policy will be very restrictive through the projected timeframe out to 2028 and where we wonder why then inflation only just approaches the 2% target by the end of that period.

We are a little less confident about the extent of easing into 2026 but see another 25 bp cut likely in December and then every quarter through next year. That would still leave the policy rate roughly in the middle of the neutral rate range estimated by the Norges Bank. In other words, the Norges Bank will be merely taking its foot of the brake, rather than pressing on the accelerator.