Can Tech and Productivity Cushion China’s Long-Term Growth Slowdown?

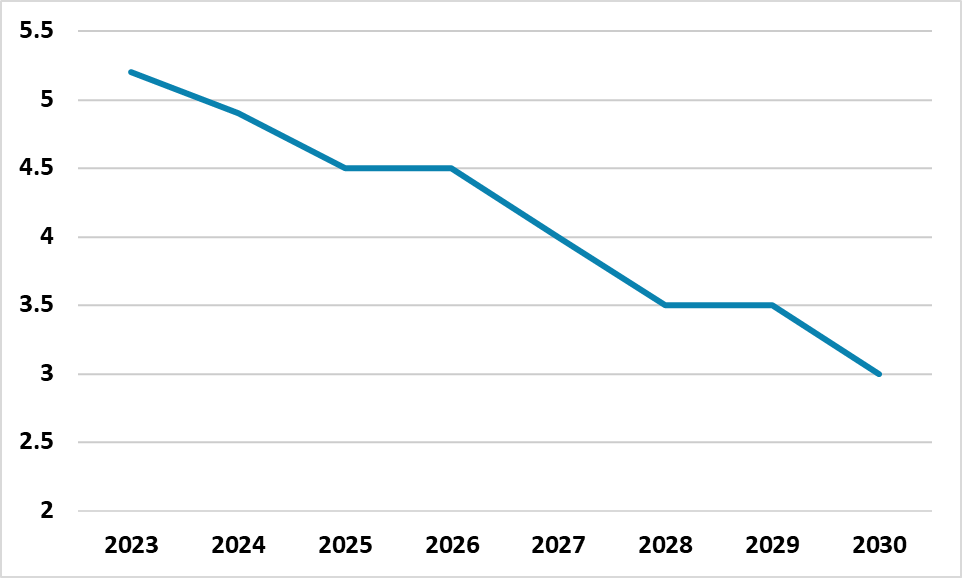

While innovation from China’s technology initiatives can provide help to cross over productivity, the benefit will likely only be modest due to the downgrading of the private sector in China and the lack of openness to inward trade. The structural slowdown in capital productivity will dominate. Combined with a peak in the labor force/employment, this is likely to mean trend growth of 3% or just below from 2027 onwards. Stimulative fiscal policy can lift actual growth above trend growth, but likely only modestly.

Our long-term growth view is for a slowing of China’s trend growth to below 3% later in the decade, due to population aging and slowing productivity growth with less investment. Can this be changed by focusing on new high-tech industries and cross over productivity (total factor productivity) enhancements?

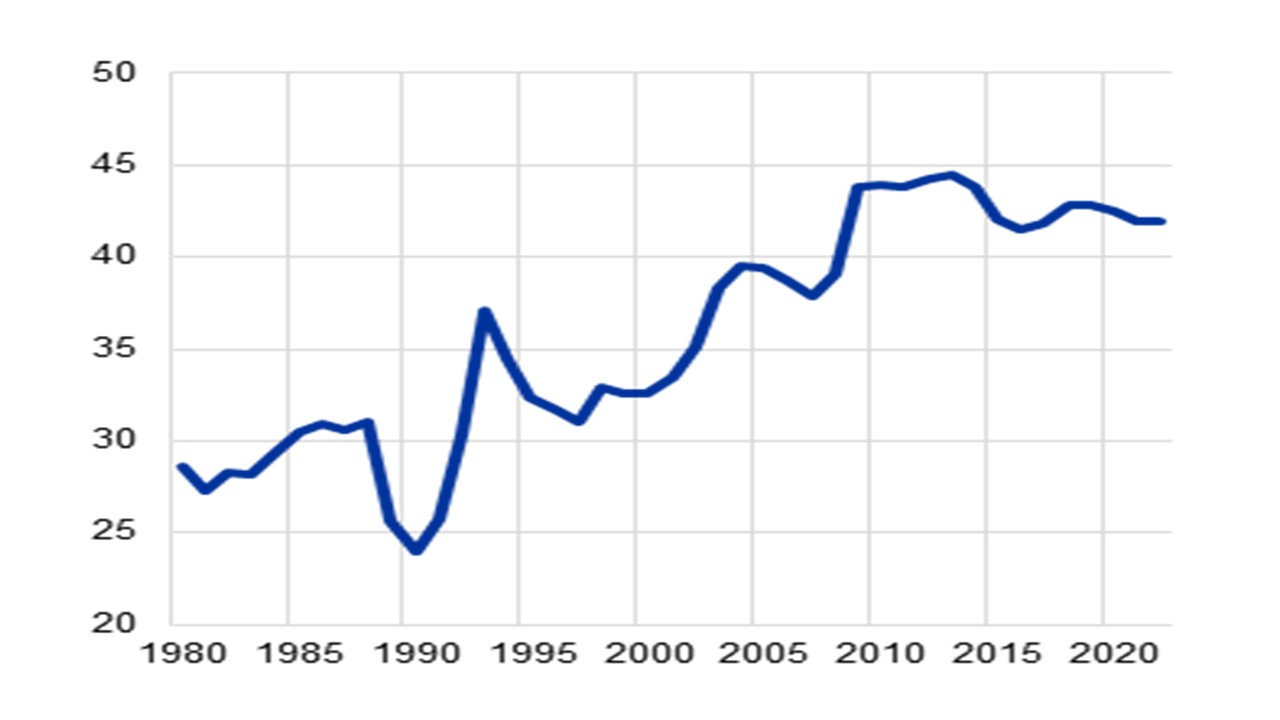

Figure 1: Investment Share of GDP Peaking (%)

Source: ECB (here)

China’s authorities’ strategic policy is that the future is based on new industries and not just macro stimulation to hit a high real GDP target. The current focus is on boosting an array of industries to drive forward innovation and higher cross over productivity (total factor productivity TFP). In the field of AI, China is the key challenger to the supremacy of the U.S. tech companies. In the field of Quantum computing, China is also a key competitor with the U.S. (here). Can this focus on high-tech industries help to cushion the structural slowdown in GDP growth we outlined in November (here)?

We remain sceptical as China falls short on three of the four factors for long-term structural growth success and movement towards a high-income country. The rule of law for private sector momentum is worsening this decade compared to 1990-2019. The high-tech manufacturing push is directed from the center as China has swung back towards a socialist state driven planning for growth and downgraded the role of the private sector in the wider economy. Secondly, China does not score well on open and competitive markets, which are a key driver to better long-term TFP productivity growth. Finally, though investment in education and human capital development is good in tier 1 cities, lower tier cities and rural areas do not achieve these high standards. Meanwhile, China AI helps, but is not a game changer as the main benefits come to replacing high-income workers and China has less than DM economies. Overall, technology can help lift TFP a bit in China, but the ECB recently estimated that it has slowed to 0.7% in the 2007-18 period (here). With capital productivity slowing noticeably, plus labor productivity growth only modest, this mean that overall productivity growth is likely to still slow in the remainder of the 2020’s and 2030’s.

A second alternative to boost productivity growth is to accelerate the remaining shift from rural to urban, where high productivity jobs occur and could boost labor productivity. The state council has announced a five-year plan to significantly relax Hukou laws for mid tier cities that slows internal mobility in China and also led to high uncertainty/large precautionary savings for workers that do not have full Hukou status in the tier 1 or 2 cities. However, local authorities will likely resist the plans, while President Xi is also keen on control and the Hukou system is part of this wider system of social control. China also wants food security, which means a desire to only have slow rural to urban migration and avoid disrupting domestic food production.

Thus we do not see China being rescued from the key structural slowdown forces.

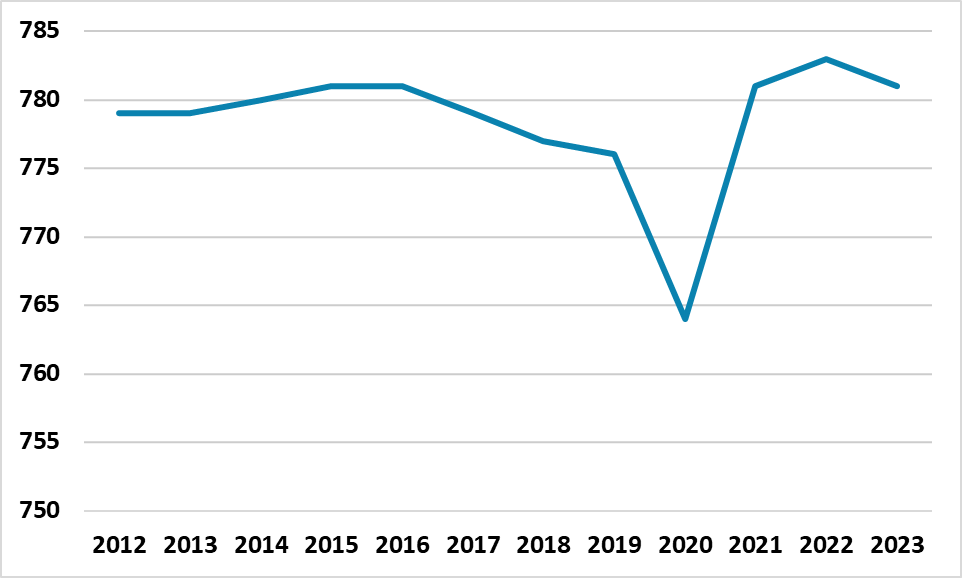

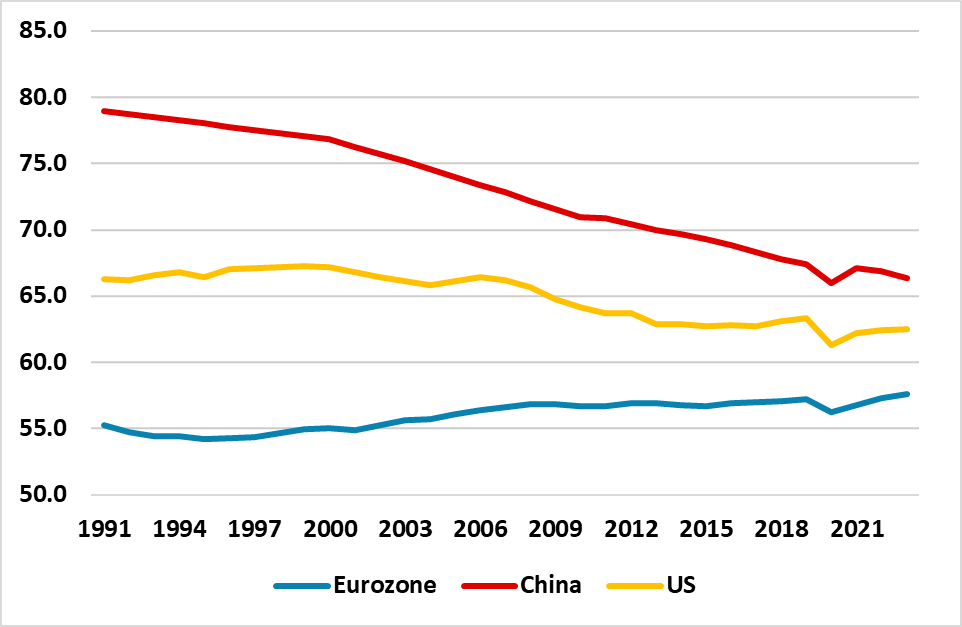

· Labor force/employment peak. Net population growth is turning negative in China and it is politically highly unlikely that China will accept large scale inward immigration to boost the labor force (Figure 2). Secondly, female participation rates are high by EM country standards and not far below the DM average. Finally, the challenge is to increase the rate of over 55 working, given the low retirement age in China. China has finally passed plans to increase the retirement age by 3-5 years between 2025 and 2040 (here), which will help by producing a modest rise in over 55 employment, but may not produce a major new rise in the overall labor force or labor force participation rate (Figure 3) and employment on a multi-year view. China slowdown in labor force participation is due to a greater proportion retiring over 55 and the surge in university education. Labor force and employment remain close to a peak, which is a major drag on structural growth.

· Slower capital productivity. China productivity growth has slowed through the last decade and is set to do so still further due to the slowdown in investment. China infrastructure wave is slowing, while spare capacity exists in a number of industries. This all points to a continued slowdown in capital productivity and more than offsetting any increase in resources working smarter (TFP).

Overall, we maintain the view that overall productivity will keep on slowing and is the second structural headwind to China growth alongside peak employment. This all points to long-term structural growth slowing to 3% by 2027 and below by the end of the decade.

Figure 2: Labour Force (Mlns)

Source: World Bank

Figure 3: Labor Force Participation Rate (% of population)

Source: Datastream/Continuum Economics

In terms of our long-term forecasts, we also need to take account of stimulative policy that could lift growth above structural growth trends. China’s authorities’ relative inaction on fiscal policy compared to 2009 or 2015 reflects both a focus on quality growth at a slower pace and fiscal space being more limited by the high overall government/corporate/household debt to GDP – now higher than the U.S./EZ. Additionally, the bias towards production and against households means that China’s authorities are likely to only undertake modest improvement in structural safety nets (health/unemployment/ pensions), which means only a small boost to consumption as precautionary savings remain high. Thus we look for some fiscal stimulus to boost overall growth above long-term structural growth trends in 2025-30 but at a modest pace. This shapes our long-term China forecasts in Figure 4.

Figure 4: China Long-Term Growth Forecasts (%)

Source: Continuum Economics