China Banking Stress Tests: The Good, The Bad and the Ugly

The good news is that China’s 19 major domestic systemically important banks (D-SIB’s and 72% of loans) hold up well under most solvency and liquidity tests, though some capital shortfalls start to appear with a moderate or severe NPL sensitivity shock scenario. The safety net would likely be capital injections including from central government as occurred with the largest 4 banks in 1997-04 or takeover and mergers. However, small and mid-sized banks shortfall of capital in the more severe sensitivity would test China authorities crisis management and response capacity that could mean a lower tier bank crisis is not quick to be resolved.

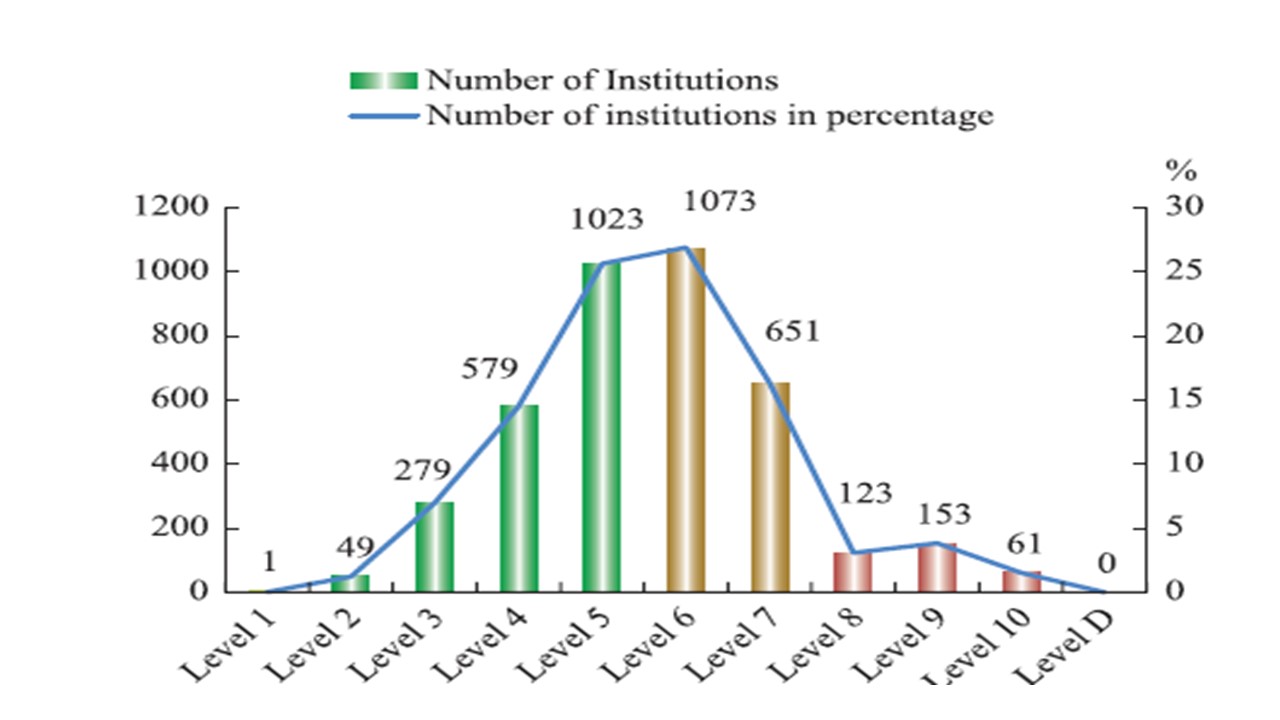

Figure 1: PBOC Rating of Banking Institutions (Q2 2023)

Source: PBOC Financial stability review 2023 (here)

The PBOC 2023 financial stability review has just been released (here) and provides an insight into PBOC monitoring and surveillance of the banking system, as well as new stress tests (special topic 4). The good news is that the monitoring is active across the banking system, with the PBOC rating banks from level 1 to 10 – level 8 to 10 are in the red zone and in need of action. The main 24 largest banks including the 19 domestic systemically important banks (DSIB’s and 72% of loans), are mostly level 2-3 with only one at level 7 (Figure 1). The tail of red banks are small mainly rural banks but also some mid-sized banks. Though they total 337 banks, they are only 1.7% of the total asset of the banking system. The numbers are also down on 2019 as the PBOC has been active in forcing weak banks to take on more capital/restrict lending/reduce leverage and in the worst case has worked with local governments to engineer takeovers and mergers. A tough U.S. style prompt corrective action has also been trialed in a number of provinces. The PBOC and China authorities have also been active in educating the population about the Yuan500k deposit insurance (per person per bank). Though these ratings (Figure 1) are based on data through end 2022, the new stress tests provide some forward looking insights. All 19 DSIB’s passed the solvency test based on a macroeconomic stress test of mild (+3.5% growth in 2023 and recovering thereafter) to severe (+1.1%). All 19 DSIB also remained above 12% capital in shock 1 of the sensitivity stress scenarios (Figure 2 and 3), while also passing the liquidity test. This still means some restraint on credit supply from the small and mid sized banks, but low money supply growth is also a function of low credit demand in the household and private corporations that will not be fixed by a stronger banking system alone.

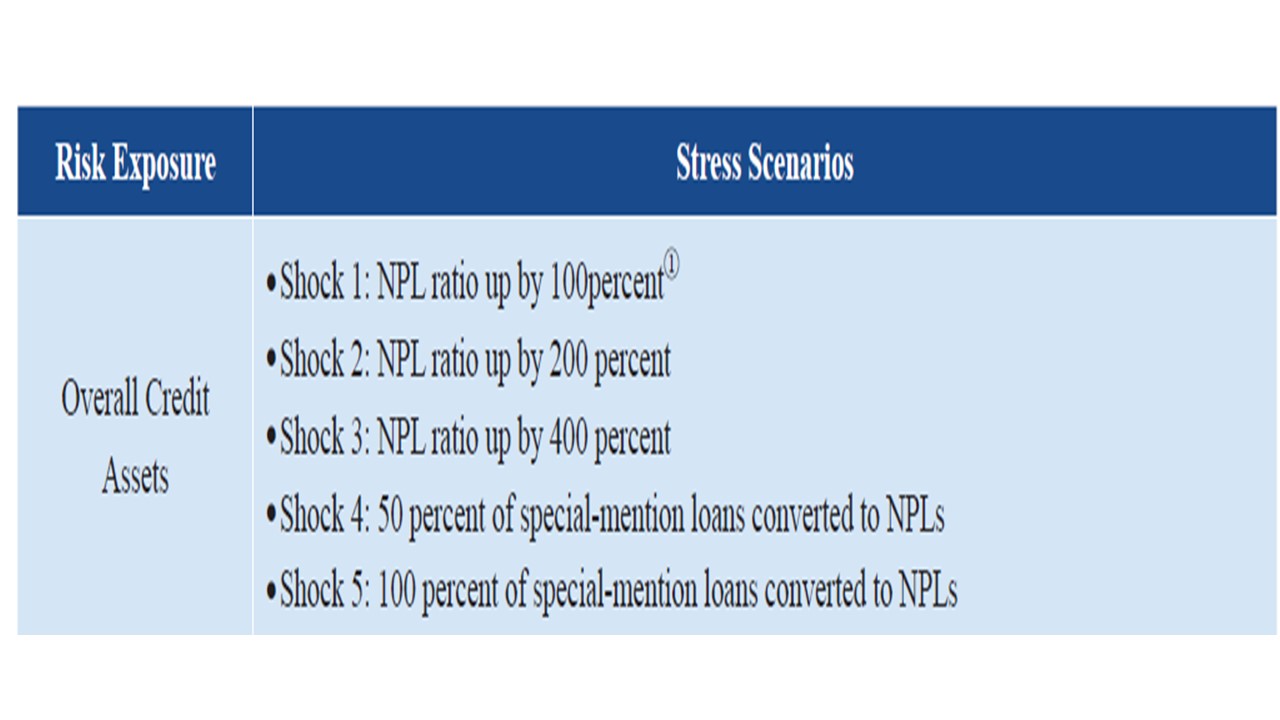

Figure 2: PBOC Sensitivity Scenarios for Solvency Stress Tests

Source: PBOC

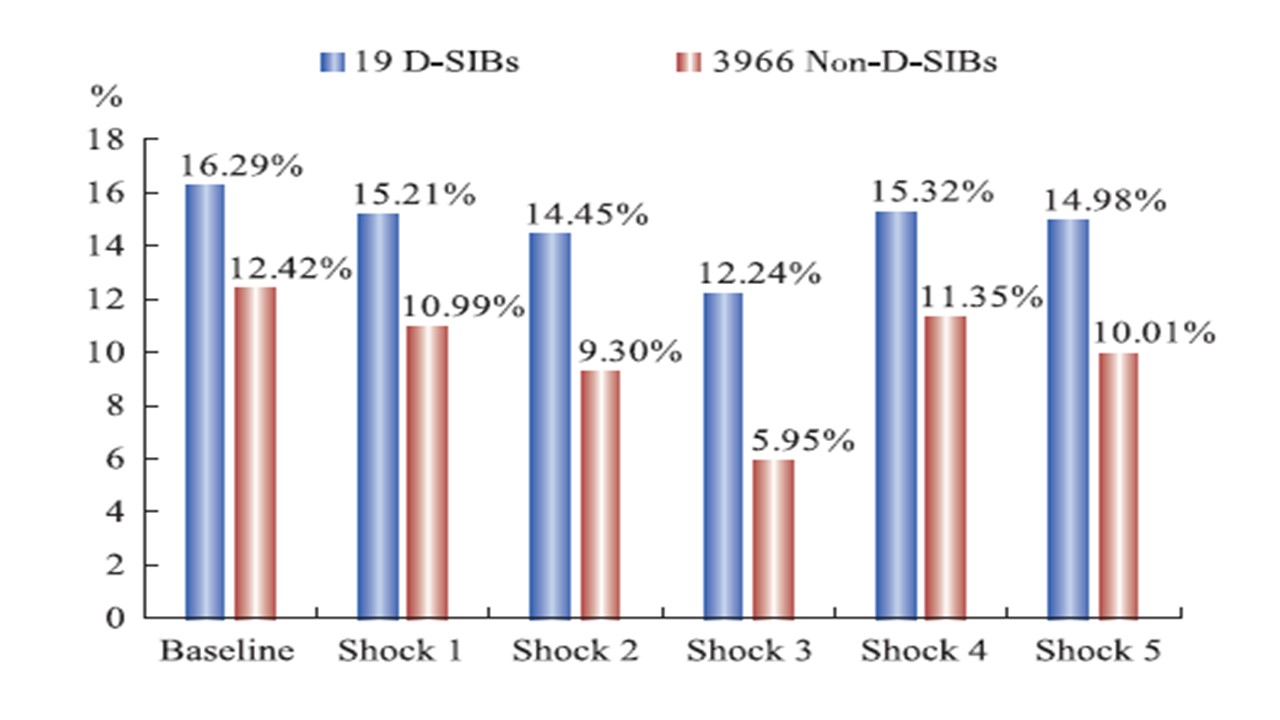

The bad news is that 2 of the 19 DSIB’s fail shock 2 (Figure 2 and 3) and 10 fall below 12% capital ratio on shock 3, though overall the DSIB’s pass. While this is more intense stress, it need not turn into a big crisis for the major banks. If shock 2 or 3 happens, then this would require recapitalization of some of the DSIB’s, which is feasible by either takeover and mergers among the top 19 or alternatively equity capital being injected including by central government. The latter option was used actively in the 1997-2004 bailout of the 4 largest banks in the wake of the surge in NPL’s from weak and failing SOE’s. The PBOC would also likely be very generous with liquidity, with the vast majority of banks across the whole system having sufficient eligible assets according to the liquidity test.

Figure 3: PBOC Solvency Stress Tests

Source: PBOC

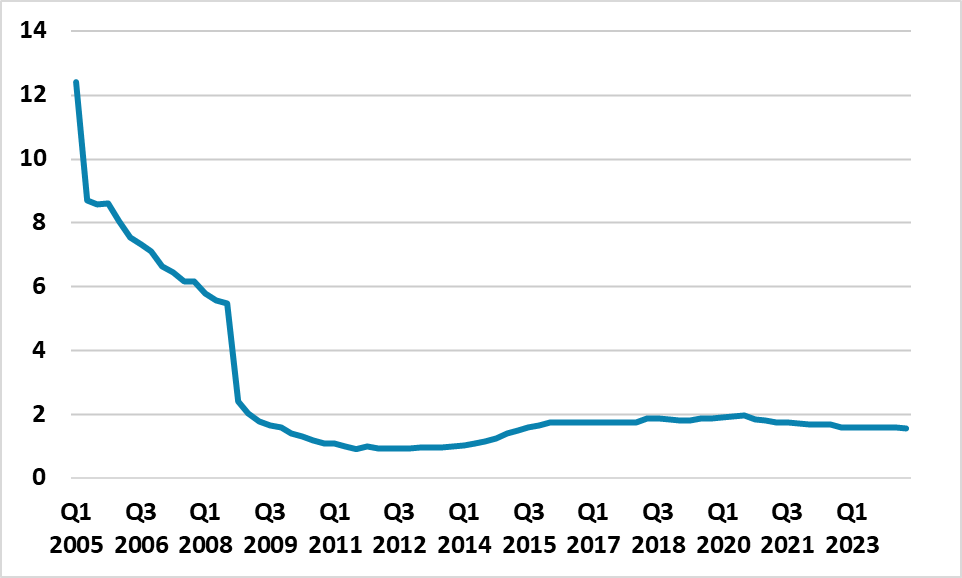

The ugly is the stress tests for the 3966 non D-SIB’s banks, which account for 28.6% of outstanding loans. Shock 1 would be testing, but shock 2 sees a huge 2020 banks fall below 12% capital ratio and 2605 banks on shock 3. While the stress test results do not reveal the scale of shortfall by banks or sub group, Figure 3 shows the scale of shortfall snowballing with shock 3 of an overall surge of NPL’s by 400%. Shock 3 is a severe scenario, as the banking system would likely not face major problems from mortgage holders given the large deposits --- though this still causes economic pain to households. Additionally, the tendency with SOE’s loans is to rollover debt, which can reduce the build-up of problem NPL’s (Figure 4). Shock 2 would see the average capital ratio for the 3918 non DSIB’s falling to 9.3%, which could for the modest failing banks be fixed by a combination of capital injections and perhaps a multi-year target to rebuild capital.

However, shock 2 would also see a surge in the very weakest that would need more dramatic action. This could mean a broadening of the process of mergers and takeover for the weakest banks. Such a process would stretch crisis management to breaking point. An alternative response would be to allow a banking regulator to set rules for insolvency of the weakest institutions as suggested by the IMF, but this is unlikely to be undertaken by China authorities. China does not want the economic hit to confidence from a succession of outright bankruptcies in the banking sector and prefers to force takeover/mergers or take into temporary official control. NPL’s will likely rise in 2025 from the lagged effect of the housing crisis but could take years to fully feedthrough – they did not peak in Japan until 2001!

Figure 4: Official Estimates of NPL’s (% of Loans)  Source: Datastream/Continuum Economics

Source: Datastream/Continuum Economics