Western Europe Outlook: Inflation Succumbing?

· In the UK, downside economic risks may still be materializing as the tighter monetary stance has far from fully bitten. This accentuates and/or prolongs an already negative domestic backdrop that may now stretch into 2025. The BoE has already paused and will likely ease next year and further through 2025 as inflation eases.

· As for Sweden, the risks to the downside also seem to be materializing as aggressive Riksbank policy hikes take effect and with resulting demand weakness now marked enough to be having discernible effects in paring back price pressures. As a result, the economy may now be in recession that could persist into 2024.

· Alongside what now is even clear below-target inflation, we have revised down our below-par Swiss GDP 2024 outlook as the economy succumbs to weakness abroad and to higher interest rates. As a result, after the added SNB pause seen this month we have brought forward rate cuts which we now envisage from mid-2024.

· In Norway, after the unexpected hike this month, we believe marked policy tightening will take a clearer toll on activity and underlying price pressures. Particularly given its most recent rhetoric, Norges Bank policy has peaked, and despite it suggesting the contrary we see clear rate cutting from next year and into 2025.

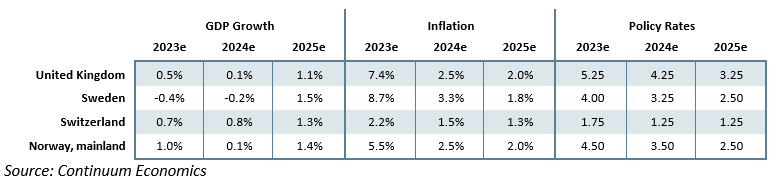

Forecast changes: Compared to our September Outlook, GDP growth forecasts have again seen mixed developments, slightly weaker for the UK and Norway for next year. But inflation news of late has still led to some base effect induced upward revisions to the 2024 outlook, but where these mask what are still see a return to central bank inflation targets by the end of next year.

Our Forecasts

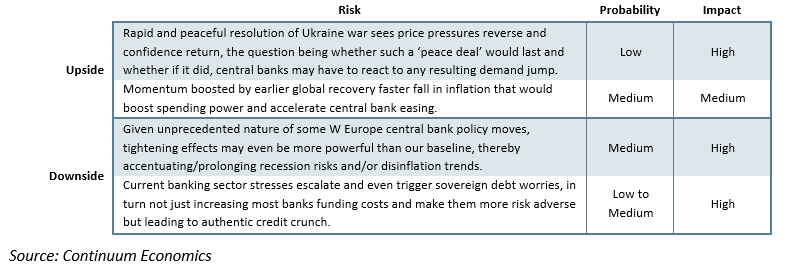

Risks to Our Views

Common Themes

There continue to be clear cross currents across Western Europe’s economies that may continue into 2024 and possibly beyond, all inter-related. Firstly, while we have made little alteration to the 2024 outlooks for all four countries, they remain very much below consensus, not only for next year but also largely now the case for 2025 too. Second, these actual or near recession conditions obviously reflect the growing actual and anticipated further impact of interest rate hikes – this effectively having added to, if not replaced, energy as the concern for beleaguered consumers. But the impact is already clear in the manner in which all four countries have seen private sector credit slow, if not contract. To us, this is partly being driven by central bank balance sheet reductions, although, even in Norway where the latter is not occurring, credit growth is negative in real terms. Secondly, after what we think have been extensive and probably excessive rate hikes those respective W European central banks have become more wary about further hiking, all pausing in decisions in their respective latest decisions. All retained tightening biases, but with a clear hint that policy may have peaked, albeit qualified and with attempt to persuade (ever-more doubtful) markets that no early easing should be expected.

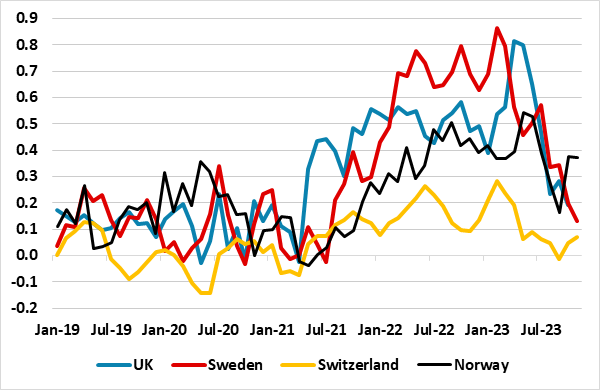

This brings up the third theme and possibly the explanatory factor for the slightly different behavior and for recent market reaction, namely recent core inflation dynamics. In order to capture these dynamics on a short-run basis we have updated the computed seasonally adjusted core CPI rates for all four economies that we first highlighted three months ago. Aware that any single-month reading may give an aberrant reading we have again smoothed the m/m data via three-month moving average as seen in Figure 1, all of which show clear signs of softer underlying price pressures. What is clear is that for the SNB, the underlying inflation picture has never been that intense and has eased nonetheless of late. For the UK, the still lack of a large MPC majority to keep policy on hold may partly reflect the manner in which softer price pressures signs have arrived only of late, this also very much being the case for the Norges Bank.

This brings up to what we would regard as the fourth theme, albeit one based on extrapolating the softer core price signals seen in Figure 1, this being something we think is sensible given the downside activity risks we see in H2 this year and into 2024. Indeed, this recession-like picture not only reinforces an outlook likely to see collective price pressures dissipating further but also means that central banks are likely to see a real economy backdrop into 2024 that surprises on the downside. The result is theme five, namely that all four central banks will have both the scope and rationale to start cutting rates by mid-2024, although the SNB may be reluctant to do so as it has already shown a willingness to decouple from the ECB and has cumulatively tightening by less on official rates!

Figure 1: Short-Run Core CPI Trends Continue to Wane

Source: Datastream, CE- computed seasonally adjusted core m/m measures, smoothed

UK: Sustained Stagnation?

For some time, the UK economy has teetered around formal recession, albeit with clear volatility whether that be for domestic demand or overall GDP. But both have showed more definitive weakness of late and we think that the economy risks seeing the contraction we project this quarter stretching into 2024. More likely, we see nothing better than continued stagnation; after all, non-government activity is now at the lowest in year. Indeed, while we have upgraded the GDP outlook for this year by 0.3 ppt to 0.5% due the official data revisions, we see only a fragile and anemic economy through 2024, but where the average growth rate of just 0.1%, admittedly only an effective 0.1 ppt downgrade from what we envisaged three months ago. This (as suggested above) is tinged with downside risks that includes an even clearer and more protracted correction in housing, both in terms of prices and turnover. This 2024 GDP projection is below consensus thinking, whereas our modest 1.1% projection for 2025 is nearer average thinking, albeit where this consensus has been on the slide for some months only now and belatedly coming into line with our more long-standing thinking. All of which reflects the impact of the sizeable tightening in monetary policy with perhaps as much as half of it yet to feed through into the real economy and where tighter financial conditions are being accentuated by the BoE balance sheet reduction. Indeed, it is notable that both the level of bank credit and especially bank deposits continue to decline.

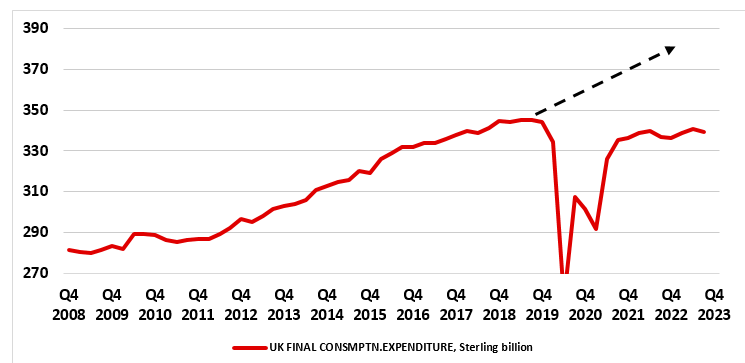

This scenario may seem to be in conflict with some recent business survey data, at least outside of clearly contraction construction – the latter may continue to drop through 2024 and 2025. Business investment is seen contracting too but less severely, despite recent added tax incentives in the recent Autumn Statement. Notably fiscal policy is going to be increasingly restrictive as frozen tax thresholds bite and government spending is contained, this occurring even under the auspices of a likely Labor administration that is likely to win a general election due in the next 12 months. Indeed, current fiscal plans that envisages a shift to a primary budget surplus by 2025 are more likely to see the headline budget stuck at well over 3% of GDP rather than fall. In turn, this means no drop in the debt to GDP ratio. But that tax threshold freeze, together with still-high savings rates, increased debt servicing, negative wealth effects and a deterioration labor market (the jobless rate rising to above 5% in 2025) will mean that consumer spending may even contract slightly in 2024 after a near zero outcome for this year and with little recovery anticipated for 2025. Such weakness is nothing new (Figure 2)!

This consumer weakness has helped curtail imports but the latter will recover somewhat from current depleted levels, while Brexit related distortions and a slower global economy weigh on exports. As a result, the likely less-negative current account deficit we see this year (down to 3% of GDP) may not improve further in either 2024 or 2025. But some recovery in imports will act as a safety-valve in helping restrain what already seems to be waning domestically generated inflation, the latter having started to show more definitive signs of slowing of late given the drop in the core and m/m measures (Figure 1). The combination of the above will bring CPI inflation down clearly, this causing the largely unrevised CPI outlook where we still see a rate of 2.5% next year and the 2% target returned to by end-2024 and staying there through 2025.

Figure 2: Consumer Weakness in Perspective

Source: ONS, dashed line is pre Brexit vote trend

As for the BoE, after 14 consecutive hikes, dating back to December 2021, and encompassing 515 bp of cumulative tightening, the BoE now looks to be on hold, albeit with the MPC majority very much seeing no early easing and even retaining a tightening bias. However, there does seem to be growing wariness that the economy is facing the kind of risks discussed above, while inflation is surprising on the downside to a degree that this may be more formally acknowledged in the next (Feb 1) Monetary Policy Report, especially if a more restrictive fiscal outlook is incorporated. We are even more of the view that policy has peaked and as these downside risks materialize, the BoE will be forced to start easing in Q2 next year, with 100 bp of cuts in both 2024 and 2025. Such an outlook is consistent with history; the average gap between the final rate hike and the first cut is around seven months since BoE independence.

Sweden: Riksbank Balance Sheet Reduction Spill-Overs

The recession is very clearly continuing, this evident in official data as well as in business and consumer survey numbers. Riksbank policy is biting strongly, not surprising given the extent of rate hikes but also the speed with which they hit Swedish activity due to the mortgage market being skewed so much to variable rates rather than fixed. Perhaps most discernibly, this is hitting the housing market, with an absolute plunge in transactions (Figure 3) that we do not see being repaired until well into the coming year, if not longer. But we continue to think that Riksbank policy is also biting unconventionally as its balance sheet reduction has caused a marked drop in bank deposits of over 6% in less than a year and where this weakness is affecting banks willingness/ability to lend and is thus accentuating demand driven weakness in credit growth. Indeed, private credit growth is contracting clearly, chiming with the drop in bank deposits. With this in mind, we see the current contraction in Swedish GDP persisting into 2024 and that the cumulative drop will be almost 2%; this assumes a modest recovery from Q2 next year. However, the risks are skewed to the downside, not least given the emerging weakness in neighboring economies and the uncertainty about the banking backdrop. There will be no boost from fiscal policy, the slight opposite given the recent Budget Bill for 2024, although the actual headline budget gap may rise slightly to just under 1% next year and remain there in 2025. Regardless, we have made only minor adjustments to our GDP outlook. After a drop of 0.4% in 2023 GDP , the real ‘story’ remains the further decline for the 2024 picture, this downgraded by 0.1 ppt to a well below-consensus fall of 0.2%, albeit not dissimilar to revised Riksbank thinking. But the recovery that starts next year may still only generate a par-type outcome in 2025 of 1.5%, also very much below consensus thinking.

In terms of detail, the erosion of households’ purchasing power has contributed to a sustained decline in household consumption since H1 2022 and with a 2%-plus drop on the cards for this year. Some recovery will emerge in 2024 as inflation falls but the 2024 pace may be barely positive, impaired by the emerging rise in unemployment with the rate moving decisively back above 8% in 2024. This may mean that wage growth next year may fall from this year’s 4%. As telling is the likelihood that housing construction (which has already fallen steeply due to lower house prices, higher construction costs and more expensive financing) continuing to contract next year. As a result, house prices (already down some 15% from the peak of early-2022) may drop further.

But exports will also fare less well into 2024, but with still soft imports meaning that with the current account surplus possibly rise towards 5% of GDP this year and persist in to 2024 and 2025 helped to weaker imports. All of which will result in an output gap of over 2% appearing through 2024, effectively a 4 ppt swing in two years!

Figure 3: Swedish Housing Turnover Plummeting

Source: Stats Sweden

Thus should accentuate the recent signs of a broader fall in underlying inflation, this very evident in seasonally adjusted m/m core CPI readings (Figure 1) which have showed a much softer profile of late. Thus, the risks may be that inflation returns to target earlier and possibly undershoots target than that forecast by the Riksbank. Thus our inflation forecasts are still pointing to a return to the 2% inflation target by the end of next year even though we have revised higher the 2024 projection due to base effects from this year. But helped by policy rate cuts, inflation may undershoot target in 2025.

Very much consistent with the unchanged policy decision last month, it now looks likely Riksbank conventional policy hiking has ended. Recent data have continued to be been mixed but both the weaker (underlying) inflation picture, and what may be growing Board concerns about financial stability risks inter-related with growing weakness in bank lending and deposits, have argued for the policy rate staying at the 4.0% level it rose to in September, thereby consolidating the unprecedented 400 bp cumulative rate rise seen in the last 19 months. Notably, the Riksbank is not ruling out a further hike but still predicts that on current policy that inflation will return to target and stay there in the latter part of its 2-3 year forecast horizon, albeit with some volatility due to energy prices. The Riksbank is not suggesting any near-term policy reversal but has brought forward slightly its anticipated first easing. We think instead that rate cuts will likely emerge by mid-2024, with 100 bp of easing envisaged for both 2024 and 2025. The question is whether the Riksbank will scale back its balance sheet reduction plans too!

Switzerland: SNB Decoupling to Continue

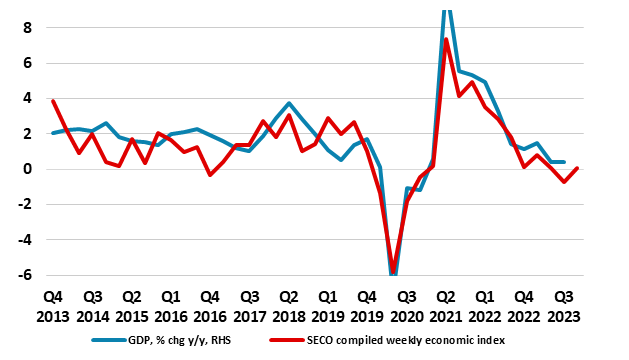

GDP growth has been volatile of late but the underlying trend has been very much sub-par, this being in accordance with our long-standing view. Indeed, survey data are weak (Figure 4) and actually falling to a degree that even threaten (an admittedly shallow) recession, very much consistent with the downside risks that beset our projections into 2024 and beyond. They range from the risk of property and financial market corrections; the transmission of monetary policy turning out to be stronger than currently assumed; even more spill-over from weakness in Germany and also a possible energy shortage in the coming winter 2023/24 albeit where Switzerland is partly insulated from this given its large nuclear and hydro reliance.

Even so, we largely adhere to our (September) GDP projection for 2023 of 0.7%, this slightly below consensus and very much under the recently unrevised SNB projection. But reflecting what we think will be a weak EU and particularly German recovery into next year, we still envisage nothing more than 0.8% in 2024, and see nothing better than a return to trend growth of around 1.3% in 2025. In terms of detail, consumer spending is likely to provide some support, given the sound labour market situation although we do see the jobless rate inching higher into 2024. In fact employment is already falling in the export sensitive manufacturing sector and this is likely to continue into 2024. However, spending growth will be merely preserved, with the recent inflation fall in headline and core inflation likely to be partly but temporarily reversed in H2 next year as scheduled rent and energy prices hikes come through. Even so, inflation should remain (well) below target so that the CPI headline rate will average 1.5% next year and down to 1.3% in 2025. Even so, real wages may rise only modestly given the high probability of continued wage restrain across all sector. Otherwise, the Swiss franc's recent strength, coupled with sub-par global demand, will continue to hurt goods exports, while declining capacity utilization and the lagged effect of higher interest rates will curb investment activity, with the risk that the expected decline in construction investment for 2023 spills over into 2024, the later factors acting to slow import growth. As a result, the current surplus may stay just under 10% of GDP in both 224 and 2025.

It remains the case that the SNB believes that the risks related to Credit Suisse furor have been contained but not eliminated. Indeed, the banking sector is still showing some fragilities, most notably in terms the clear slowing in private credit which at under 2% y/y is the lowest since 2016. The credit slowdown is also demand driven, reflecting the clear softening in property prices which will extend through the coming year.

Figure 4: Swiss Economy Moving Sideways

Source: Datastream, SECO

As for policy, the SNB surprised no-one with a second successive stable policy decision at this month’s assessment. This probably reflected several factors, not least that core inflation has been under better control. Indeed, seasonal adjusted data suggest recent monthly core trend nearer zero (Figure 1). Against this backdrop it is not surprising that the SNB CPI projections are now suggesting a clearly below-target outcome even in the medium term. Indeed, the 1.6% projection into and through 2026 inflation arguing for a rate cut sooner rather than later. Given our forecast for 2024 inflation is 1.5%, we now see the SNB deliver the first 25 bp cut in June 2024 and then a second such move in December 2024. The SNB also removed the paragraph on FX sales and SNB Jordan indicated that this was no longer a focus, which is a signal that balance sheet reduction and tightening will slow and stop. The later may reflect currency strength concerns.

Norway: Consumed with Concerns

As we have been anticipating, the economy (at least outside of oil services) does seem to be buckling, belatedly succumbing to the downside pressures being exerted by both monetary tightening and the weakening growth elsewhere in W Europe and beyond. Indeed, activity dynamics (including a sharp slowing in private sector credit growth) have persuaded us to downgrade the GDP outlook, with the growth rate this year pared back a notch to 1.0% and a downgrade to the 2024 GDP forecast of 0.2 ppt to just 0.1%, this being very much below both consensus and Norges Bank outlook. Indeed, a recent regional survey compiled by the latter actually points to GDP declining afresh in early 2024. A recovery is still seen in H2 next year and this should continue into 2025, albeit with nothing more than a trend rate of 1.4% and with downside risks attached to this consensus-like forecast.

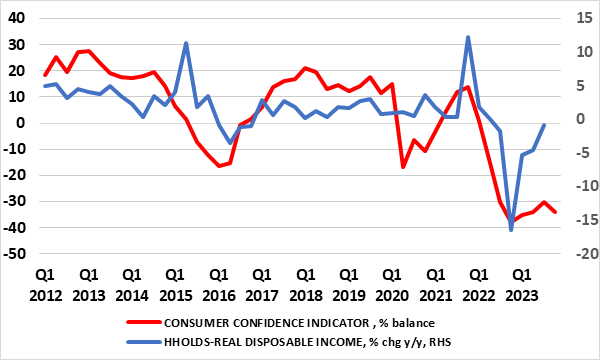

This view very much reflects 2024 seeing a second successive year of flat gross investment, albeit with a drop in construction almost certain through 2024. But the gloom is centered on households; after what most agree will be a clear fall in consumer spending this year, we do not see any recovery in 2024, with every possibility of another but more modest contraction, especially as the recent stabilization in house prices has faltered and unemployment starts to rise (as is likely). Indeed, reflecting this, consumer confidence remains near a record-low, not surprising given a likely drop in real disposable incomes of around 4% this year (Figure 5). This is in spite of the faster fall in inflation we envisage (at least compared to the consensus, but particularly the Norges Bank). Indeed, we have pared the inflation outlook into 2024 by 0.2 pp to 2.5% and this still encompasses the headline rate hitting 2% in the H2 next year and then remaining there through 2025. This is hardly surprising as the next two years should see an output gap averaging nearly 1% of GDP persisting. Indeed, more reassuring signs are already emerging not only on the headline but even the core, where downside surprises have been seen in most recent months in underlying inflation, albeit not as discernibly as elsewhere (Figure 1). But the recent weakness in the krone, which the Norges Bank is clearly trying to address with its policy rhetoric, should dissipate, if not reverse, meaning that into 2024, imported price pressures subside, thus adding to recent softer domestic signals. As a result we think the Norges Bank is too gloomy is assessing inflation still being above target even out to 2026!

Figure 5: A Clearly Concerned Consumer

Source: Norges Bank, Stats Norway

As for Norges Bank policy, and exceeding most expectations, the Norges Bank raised its policy rate by a further 25 bp to 4.5% at its Board meeting this month, thereby exercising the bias it previously communicated It seems that the Norges Bank was, indeed, very well prepared to be the last DM central bank to hike having been the first in this cycle. Why? It may have decided that the data was not persuasive enough to deter it from the hike it previously flagged, not least the CPI developments alluded to above. In addition, there has been some resilience in real activity data. But this was a dovish hike so to speak, as the Norges Bank is hardly suggesting any further such moves and has instead brought forward its perceived first rate cut to Q3 next year. Amid survey data pointing to recession and where CPI data has been distorted by swings in food prices rather than discretionary items, we think the Norges Bank is being too hawkish, not least given its own projection of an output gap of close to 1% persisting out to 2026. This output gap picture will weigh (further) on inflation and to a degree that makes us still think that that rate cuts may arrive mid-2024. We forecast 100 bp of rate cuts in 2024 and a same-sized drop through 2025.