Eurozone: The Neutral Rate – Probably Little Changed Recently Unlike Central Banks

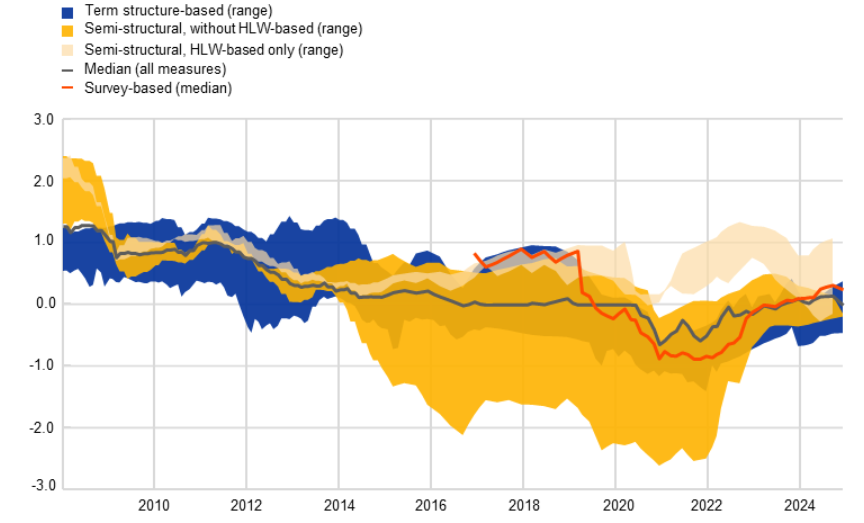

A well-advertised research paper from the ECB suggests that the real neutral rate of interest for the EZ has not changed very much in the last few years but with a likely range of between -0.5% and +0.5%, but still well below estimates for what is so-called r* prior to the pandemic (Figure 1). The research paper cites various models and notes the high uncertainty in the various estimates and also shortcomings in using r* alone to assess monetary policy restriction – something underscored by ECB Chief Economist Lane earlier this week. Even so, using the 2% ECB inflation target to turn real r* into nominal r* yields a possible policy range of 1.75% to 2.25%, an outcome flagged in a recent speech by ECB President Lagarde and which may suggest that ECB main policy rate at 2.75% is nearing alleged neutrality. However, the paper does not detail the actual factors that may be (re)shaping r* (Figure 2). Regardless, what is notable, if not puzzling, is that the BoE now suggests a somewhat higher UK r* and one that may have risen recently while the Riksbank suggest a similar outcome to that of the EZ but one that has fallen of late.

Figure 1: Various Real Natural Rates of Interest in the EZ

Source: ECB – HLW = Holston, Laubach and Williams

Following a modest post-pandemic increase, the updated range of point estimates estimated by ECB researches of the EZ real natural rate of interest has remained broadly unchanged since the end of 2023 (Figure 1) The most recent estimates of real r* span a range between -½% and +½%. Translating those measures into their nominal counterparts is measure-specific. Some of the models produce both real and nominal versions of r*, while others estimate only one version. In the latter case, the missing value must be derived by adding or subtracting the ECB’s 2% medium-term inflation target or the model-consistent medium-term inflation expectations from the model estimate. When the three estimates derived from versions of the main ECB model are factored in, the range of real r* is -½% to 1% and the corresponding nominal range is 1¾% to 3% (ie very similar to that computed by the Riksbank for Sweden) but where estimates of the nominal r* from the most recent interval range are between 1¾% and 2¼%.

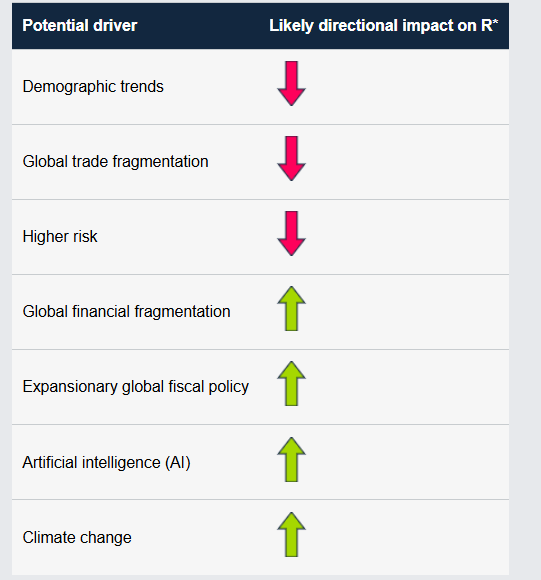

What Shapes R*

Many factors shape r* and these vary over time but have been detailed by the BoE (Figure 2). While a still historically low EZ r* may be reassuring it is notable that it actually reflects not-so-comforting factors, very likely still anaemic productivity growth, aging populations and increasing trade fragmentation. Notably, if not puzzling given that the various economies are facing similar fundamentals, is that the BoE now suggests a higher UK r* and one that may have risen by up to one ppt if late while the Riksbank suggest a similar outcome to that of the EZ but one that has fallen of late. Indeed, the BoE assertion is all the puzzling given that its recent Monetary Policy Report pointed to a weak(er) productivity causing to have downgraded its estimate of the economy’s supply.

Figure 2: Potential drivers of a change in R*

Source: BoE Feb 25 MPR

Assessing Monetary Stance

Regardless, using r* to assess the stance of monetary policy is helpful but far from authoritative. Indeed, ECB Chief Economist Lance cites at least nine factors that would need to be assessed towards creating a summary “restrictiveness” index, most largely trying to understand how the monetary policy transmission mechanism is facing. In that regard we would note that for the EZ, while a current main policy rate just 50 bp above a possible range for nominal r* would suggest policy restrictiveness is now only modest that ignores the fact that current bank lending surveys still point to banks having high and in some cases still rising credit standards, implying that the monetary policy transmission mechanism may be exacerbating policy restrictiveness. Moreover, as the ECB asserts, inherent uncertainties (see below) as well as conceptual shortcomings limit the usefulness of available natural rate estimates for conducting monetary policy in real time. Because of the multiple types of uncertainty and the focus on the short-term interest rate instrument – as opposed to broader measures of financing conditions, which can have a stronger impact on spending – the usefulness of r* as an indicator to support the calibration of the monetary policy stance is greatly limited, making it difficult to use as a rate-setting norm at policy meetings. Many models used do not construe r* as stabilising inflation in line with target but as merely indicating levels towards which interest rates gravitate over the longer term.

R* Still Very Uncertain

But estimates of r* are fraught with uncertainty emanating from uncertainties in model parameters (where the econometric methods used generate a whole set of plausible alternative estimates to the fact that r* is an unobservable variable that must be inferred from observable data – a challenge known as filtering. The latter means that model-specific estimates of r* can vary significantly when observations are added or back data are revised. Even so, over and beyond trying to assess policy restriction, tracking broad movements in the natural rate over time provides qualitative insights into underlying economic trends. Furthermore, as the ECB paper concludes, the connection between an r* defined in terms of the short-term interest rate instrument of monetary policy and the broader economy may itself change, as monetary policy transmission depends on a broader set of financing conditions – including the cost and availability of bank credit, and prices in a range of asset markets.