China: Boosting Consumption In March?

· China’s consumption medium term could be boosted by higher structural safety nets (social spending/health/pensions) and revisions to the Hukou system (shifting 200mln urban workers from lower rural to higher urban benefits). However, March NPC will likely see only further small to modest incremental structural steps, rather than the significant reform that is needed.

· Consumption will be helped cyclically by further trade in programs, but the December 30 announcement of Yuan62.5bln, initially for trade in programs, suggests the March top-up and 2026 total are unlikely to exceed the Yuan300bln in 2025. Some fiscal transfers to households could also be announced, but these are likely to be modest.

· Overall, we expect 2026 consumption to remain modest and GDP growth to be 4.4%.

What will China authorities do to boost consumption in 2026 and beyond?

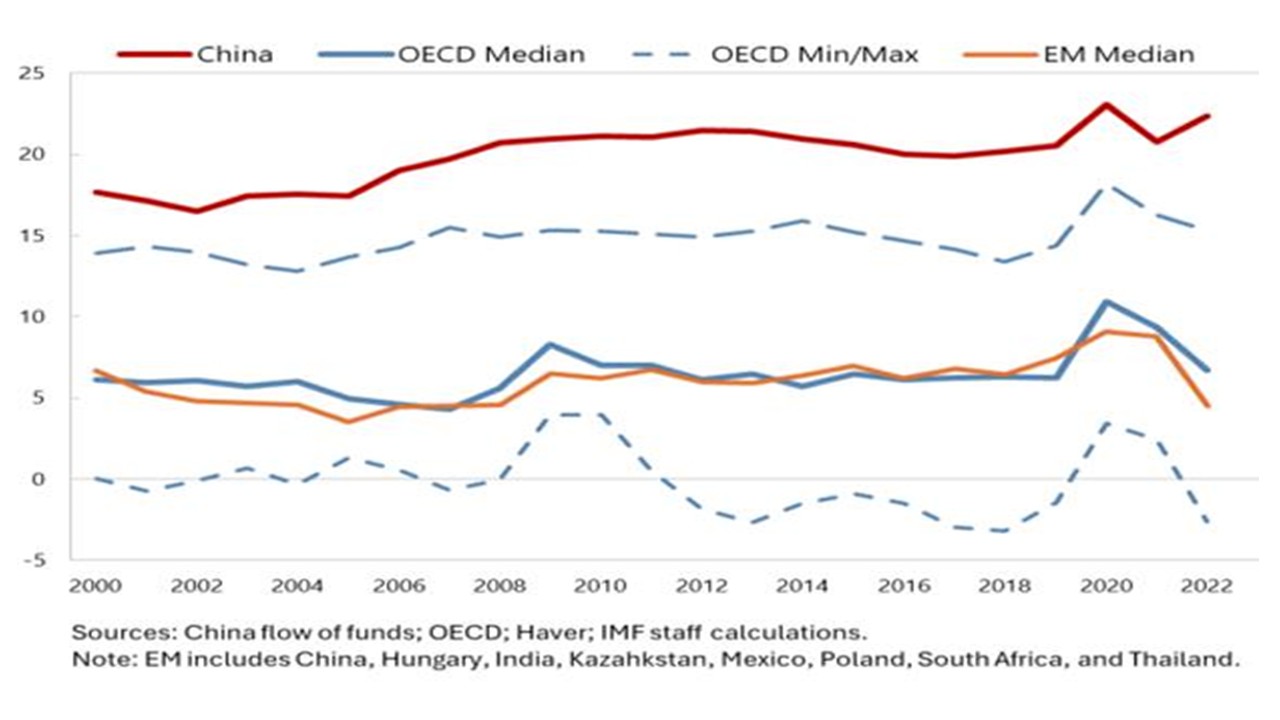

Figure 1: China versus Other Household Saving Rate (% of GDP)

Source: IMF Working paper Dec 25 (here)

China’s authorities can boost consumption via structural policies (better safety nets/Hukou revisions) and cyclical handouts or subsidies. A number of points are worth making ahead of the NPC fiscal stimulus measures on March 5.

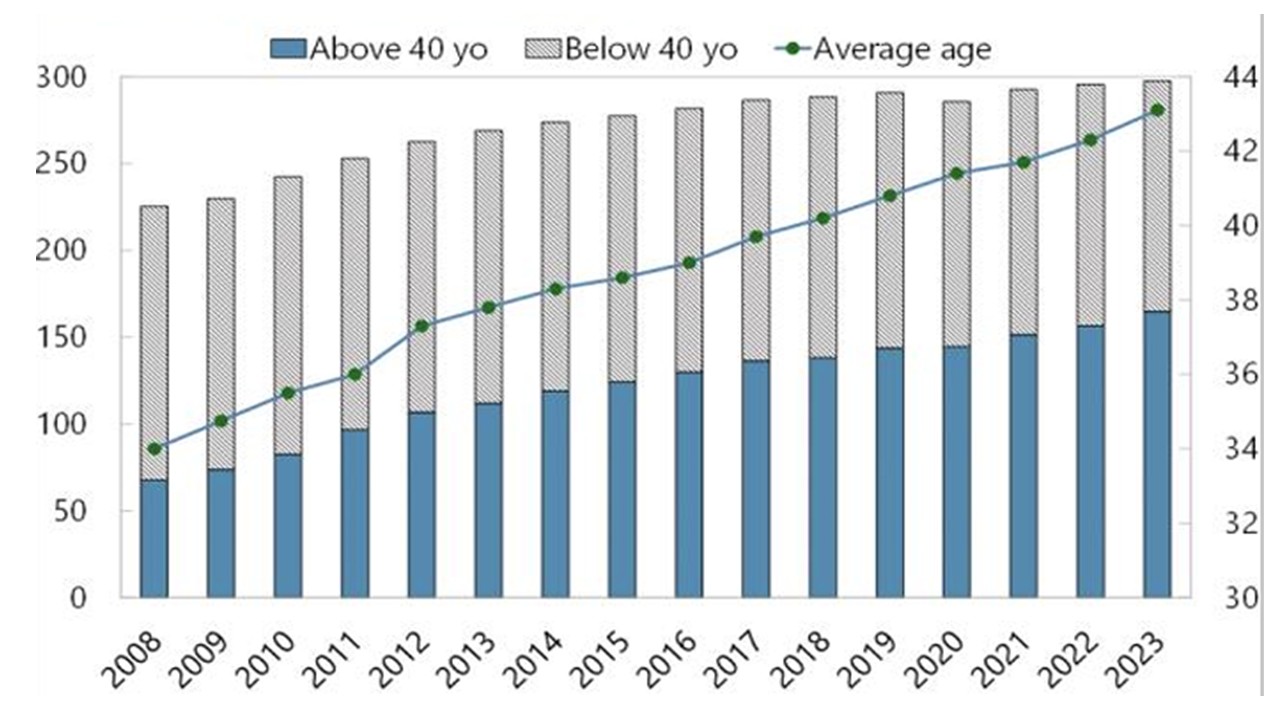

· IMF on structural high precautionary savings. The IMF have done a deep and broad analysis of the reasons behind China’s high savings ratio (Figure 1). The analysis suggests that low government social and health spending (especially) in rural areas and residency (“Hukou”) restrictions in urban areas (200mln living in cities with over 3mln population, but with lower rural workers benefits) play a significant role in increasing household savings. Migrant workers are also becoming middle aged (Figure 2), which requires greater safety nets or more precautionary savings. While China authorities have undertaken modest measures to improve structural safety nets, March NPC will likely only see further small to modest incremental steps, rather than the significant reform that is needed. President Xi remains wary of boosting households too much, in order to avoid Western style benefit systems, and also has re-emphasised quality growth in late December (in high tech and production). This tends to temper the 15th five year plan ambitions to boost consumption.

Figure 2: China Migrant Workers (LHS Numbers in Mlns; RHS average age)

Source: IMF Working paper Dec 25 (here)_

· Cyclical trade in programs or fiscal transfers. A more cyclical way for China authorities to boost consumption growth is via trade in programs or alternatively fiscal transfers to households (tax cuts/one off payments). In 2025, trade in programs helped to boost certain categories of consumption, though not overall consumption. The signs for 2026 are for small to modest measures, following the December 30 announcement of Yuan62.5bln, initially for trade in programs. Though cars traded in for EV’s can now attract a 12% subsidy, the range of household appliances supported by trade in programs has been restricted from 12 to 6. Extra money for subsidies will likely be announced in March, but is unlikely to exceed the Yuan300bln in 2025 and could end up being less! Some fiscal transfers to households could also be announced, but these are likely to be modest and fall short of optimism raised by the official emphasis on households at the end of 2025.

· No major rescue for housing or housing wealth. The IMF paper also found that the decline in residential property prices had adversely impacted consumption via a wealth effect (though partial offset by less savings for non-property owners for down payments given lower house purchases). If house prices and confidence in the housing market bottom, then it could lessen the adverse wealth effect. However, China’s authorities emphasis on quality growth is a clear signal that they do not want to reflate the residential property market, though some further measures could be announced in March to try to smooth adverse effect of the ongoing adjustment on construction starts and employment – while the 5 year Yuan10trn local government/LGFV debt consolidation plan should also soften local authority cutbacks.

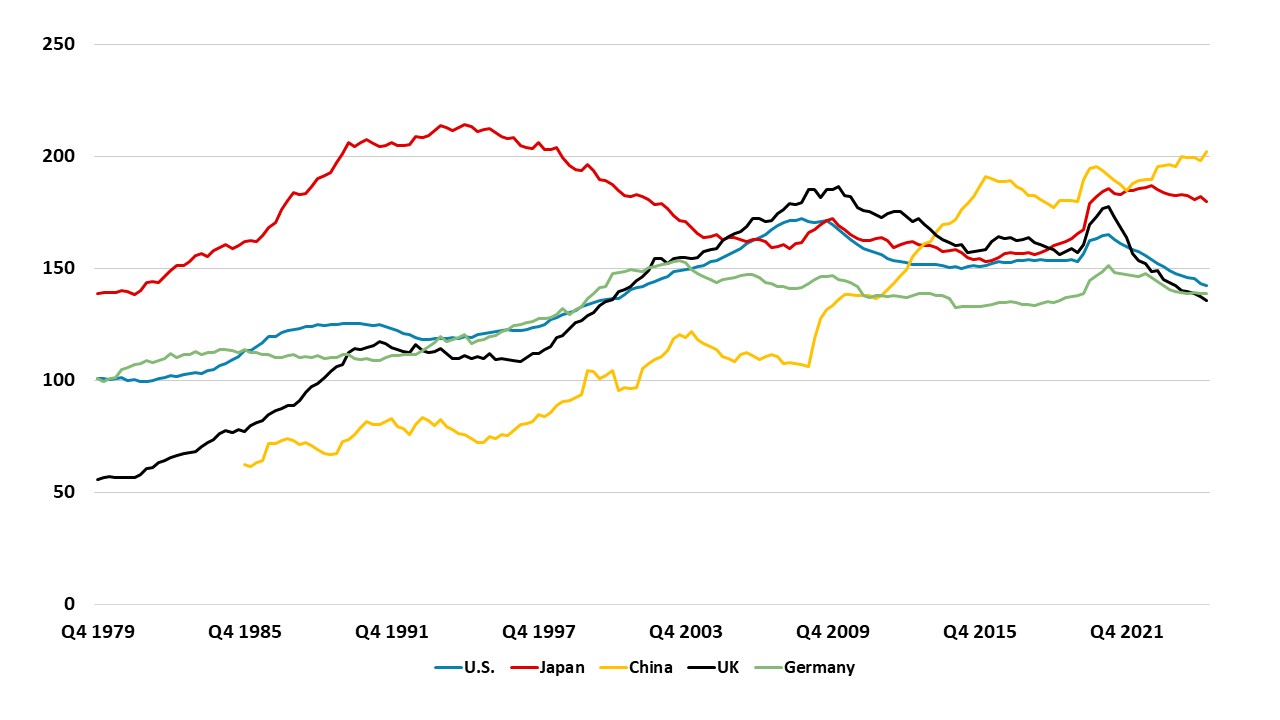

· Modest fiscal space and high debt. China’s authorities also remain concerned that fiscal space is modest rather than large. Actions over the last few years suggest that the authorities’ actions are restrained by the IMF’s projected trajectory for general government debt/GDP. With the deficit projected to remain excessive at 8% of GDP 2026-30, and a nominal GDP of 4-5%, this means a surge on government debt/GDP. Additionally, China’s authorities remain concerned about the rising trajectory of household and company debt/GDP (Figure 3), which has surpassed major DM economies. The major official concern is that excessive debt causes a Japan style balance sheet recession, with the economy insensitive to ultra-easy monetary policy. If government debt continues to rise sharply, then overall debt levels could threaten a Japan switch to debt paydowns across the economy. It could be argued that certain households and businesses are already in balance sheet recession, which accounts for the sluggish lending by banks to the private sector and households seeing more repayments than new loans. The bottom line is that growth in the 4-5% region means fiscal space for only modest easing.

Figure 3: Total Household/Corporate Debt (% of GDP)

Source: BIS/Continuum Economics

Overall, 2026 consumption will likely be modest, with consumer confidence and income expectations remaining depressed and wealth adversely hit by the housing slump. For more see our China Outlook (here). On overall fiscal stimulus, we see around Yuan2.5trn on extra government fiscal stimulus. Dec 31 also saw an announcement of Yuan295bln for 1000 projects for national strategic and security priorities, which suggests a measured and targeted fiscal easing approach. We thus forecast 4.4% 2026 GDP growth.