EZ: Labour Costs in Retreat Amid Hoarding and Workforce Jump

It is ever clearer how the labour market (and particularly labour costs) are the dominant theme for the ECB is assessing the policy backdrop and outlook. While HICP inflation continues to subside amid an economy backdrop which is flat at best, the labor market still looks apparently unmoved, with the EZ jobless rate back at a record-low of 6.4%. But this ignores both strong evidence that this reflects labour hoarding (Figure 4). It also masks not only a situation where labor supply is not only rising but actually far faster than pre-pandemic (Figure 3), but where much higher unemployment for younger workers remains the case. All of which helps explain a series of recent data releases (Figures 1-2) suggesting an easing in labour costs growth, and (particularly in regard to Q4 compensation per employee) to a degree that has surprised the ECB to the downside. But it is clear that the policy outlook is tied to how forthcoming labour costs data will fare, not least Q1 numbers that will arrive just in time for the ECB’s June Council meeting. This data should trigger what is becoming a well-advertised rate cut, the question what then.

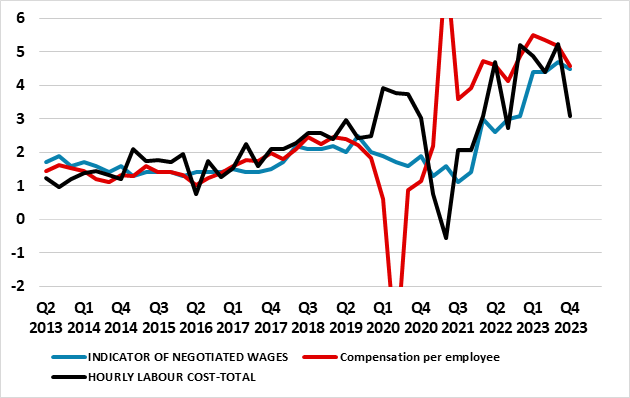

Figure 1: Labor Cost Growth Clearly Easing…

Source: Eurostat

Policy Outlook

But if the ECB remains focused on such quarterly labor costs updates then subsequent rate cuts may only arrive in September and December, hence our long-standing view that the ECB may cut only some 75 bp this year. However by year-end more durable evidence of labour costs easing should convince the ECB to continue easing and we see 100 bp through 2025! Admittedly the ECB seems very reluctant to discuss openly a possible rate cut path. But regardless, the very fact that ECB forecasts now point to headline inflation below target before and then through 2026 and the core rate at target on the basis of market rate pricing of future official rates down to 2.4% next year, very much implies a tacit ECB Council endorsement of that rate profile. With this in mind, perhaps the main risk is that interest rates cuts may be larger and/or faster than we have assumed as the monetary policy transmission mechanism proves even more powerful than we have estimated and fiscal policy prove more restrictive.

Labour Costs Drop Emerging

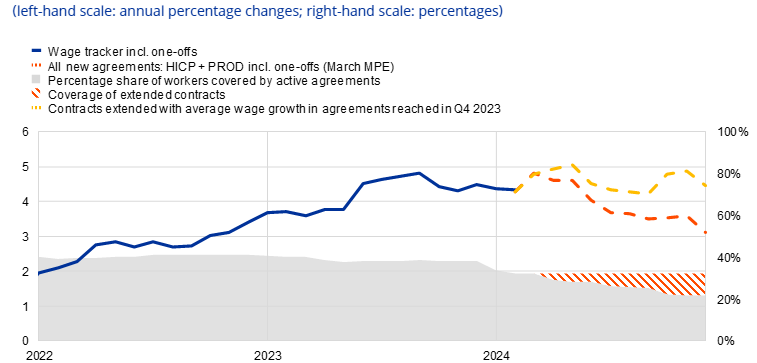

There are an array of labor costs measures the ECB has access to, and all seem to be showing a similar message, namely a reduction in the pace of labor cost increases (Figure 1). Most notable in this regard is the data on hourly wages, which has slowed to just over 3%, a pace historically consistent with hitting the 2% HICP target. Admittedly, other measures are still somewhat higher with the ECB’s favored measure having dropped but only to 4.6% in Q4 last year, albeit a result that was lower than the ECB had anticipated and which poses downside risks to its 4.5% projection for this year. In addition, the Council has drawn reassurance from its own-compiled wage tracker that does not suggest upside risks to the wage outlook (Figure 2).

Figure 2: …And Tracking Evidence Suggest Few Upside Risks

Source: ECB Forward-looking wage tracker

Mixed Jobless Signals

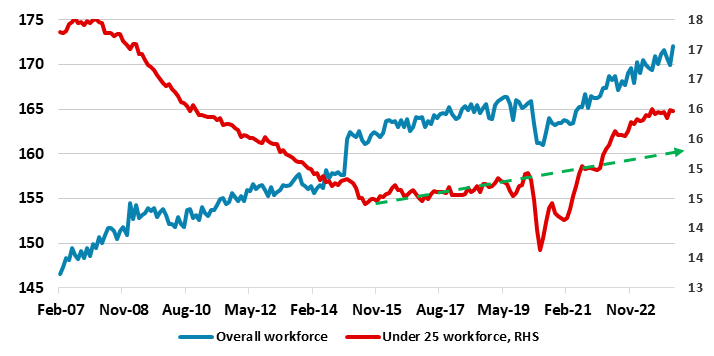

As suggested above this seems puzzling against an apparent tight labour market. The latest (February) jobless data point to a record-low in the level of unemployment with the rate back down to 6.4%. But this masks something unique to the EZ, at least amid the DM world, that is not only an increase in labor supply continues but at a pace exceeding pre-pandemic rates (Figure 3). As a result, there has not only been much actual fall in the unemployment level but also a much higher and rising jobless rate for young, they more likely than older workers to consider looking for better paid work (ie labour churning). Indeed, the rate has risen over half a ppt in the last year, albeit with clear volatility into the latest releases.

Figure 3: Labor Supply on Firmer Upward Trend

Source: Eurostat, Continuum Economics, dashed lines are pre-COVID trend

What is driving this divergence between older workers (ie over 25) and younger (under 25) is unclear over and beyond what is a weak economic backdrop. It may be the case that after the sharp fall in youth unemployment seen prior to mid-2023, more such workers were tempted back into the workforce with the prospect of actually finding employment, this possibly accentuated both by the relative and absolute costs of alternatives (such as further education) and a need to support family incomes hit by the surge in inflation.

Added Workforce Dampening Wages?

Regardless the added supply of mainly younger potential workers is likely to affect the overall ability to strike for higher wages. Meanwhile, the demand for higher wages may be sapped by both a decreased incentive to find alternative work with higher remuneration and by younger works having much lower perceptions and expectations of inflation – at least according to the latest ECB Consumer Expectations Survey. And history highlights how important turning points in youth unemployment have been is pre-dating turning points in wage pressures.

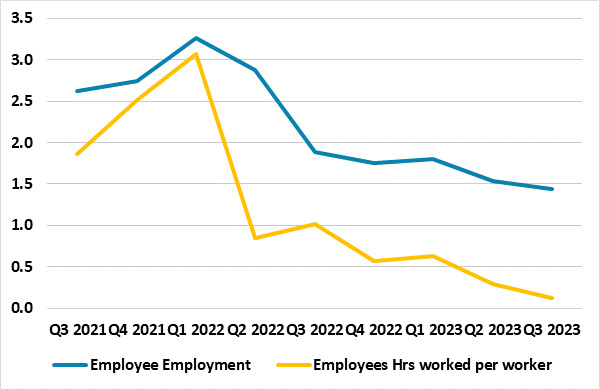

Figure 4: Hours Worked Drop Hints at Labour Hoarding

Source: Eurostat, % chg y/y

Labour Hoarding and Implications Ahead

The divergence is older and younger workers, and the fact that an apparently record-low jobless rate has not caused a sustained wage jump, may be that companies want to retain experienced workers amid what have been clear labor shortages signaled by business survey data, albeit the latter still suggesting an ever-clearer wariness about taking on new staff. It may also be simple labor hoarding, which is companies holding on to more workers than necessary in the downturn, has occurred in previous EZ cycles. Labour hoarding can be defined as that part of labour input which is not fully utilized by a company during its production process at any given point in time. Under-utilization of labour can manifest itself in various forms, such as reduced effort or hours worked, and the shift of labour to other uses, such as training. From the company’s point of view, some labour hoarding may be optimal given the fixed costs associated with adjusting staff numbers. These costs include costs of recruitment, screening and training of new workers, as well as costs related to the termination of contracts such as severance pay. Therefore, in the face of a downturn in activity, companies may prefer to reduce labour input, at least to some extent, by shortening the hours worked, which is less costly than reducing staff numbers. This seems to be occurring (Figure 4) as the solid growth in employee employment has increasingly come alongside a drop in the growth of hours worked. Indeed, in trade and IT, the two areas of firmest employment growth, hours worked have fallen!

Such labour hoarding has other repercussions over and beyond helping explain reduced wage pressures. Importantly, it suggests less appetite, if not ability, for companies to take on new staff once a recovery occurs, this therefore likely to hold back the pace of any such recovery, a view very much entrenched in our still relatively subdued real economy outlook!