UK Budget Review: Higher Taxes But Still a Marked Fiscal Boost

Despite a focus on hefty tax rises of some 1% of GDP, the Budget also sees borrowing rise by a similar amount so that a sizeable surge in government spending mean this is one of the largest fiscal loosenings in recent decades. But the boost to GDP growth is temporary and modest and where any improvement in the potential is considered to be (far) too long-term to be encompassed in this five-year outlook. As a result, there is a temporary boost to CPI inflation which may make the BoE less inclined to cut rates any faster than the 25 bp per quarter we envisage out to end-2025. This may have some bearing on the gilt market, especially as the headroom against the new fiscal rules is less that some had hoped.

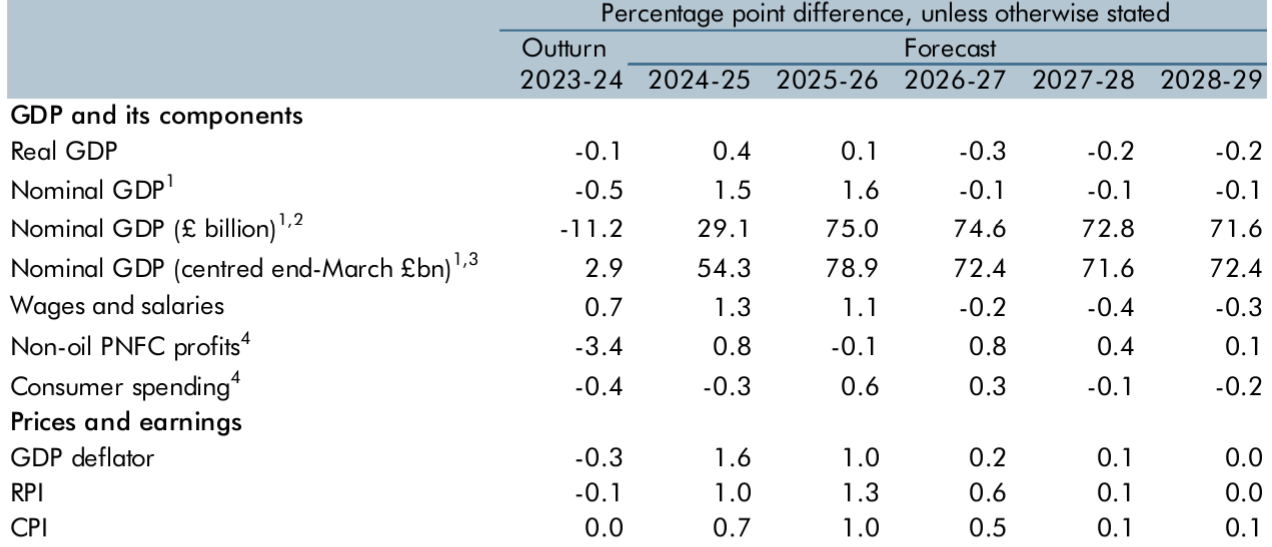

Figure 1: The (Surprising) Revisions to the Economic Outlook

Source: OBR, change compared to March Budget

This new Labour Government has faced a difficult judgement, partly made more difficult by its own making in terms of communications. Very clearly, it has been trying to stress that it is attempting something different with a break from the past. Certainly, and backed by an OBR critique, it can blame the previous administration for a still – downbeat economy and partly an inter-related fiscal hole that necessitated radical action, in the form of stepped by government capital and day-to-day spending. But the trick Chancellor Reeves needed to pull is to make sure that the tax rises and added borrowing financing these measures do not have a protracted impact on activity via damage to sentiment – business, consumer and investors – that could mean the Budget backfires as a means to resuscitate the economy. To some degree she may have succeeded.

Regardless, and as the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) stresses, these fiscal measures represent one of the largest fiscal loosening of in recent decades. It delivers a large, sustained increase in spending, taxation, and borrowing. Budget policies increase spending by a little over 2% of GDP a year over the next five years, of which two-thirds goes on current and one-third on capital spending. Half of the increase in spending is funded through an increase in taxes, mainly on employer payrolls, on assets, and through greater tax compliance. The other half of the increase in spending is funded by a 1% of GDP) a year increase in borrowing.

As a result, Budget policies boost output in the near term, but leaves GDP slightly lower than previously envisaged in five years. Indeed, the measures deliver only a temporary boost to GDP in the near term amid some crowding out of private activity in the medium term, with it estimated that the policy package boosts real GDP by 0.6 ppt at its peak in 2025-26. As for a GDP aspiration of getting growth to 2.5%, this is still far away, although the OBR acknowledge that if the increased level of public investment were sustained, it would permanently raise supply in the long term and by significantly more than it does in the forecast period. However, over the forecast period the policies result in a clear output gap emerging that acts to push up CPI inflation by around 0.5 ppt point at their peak, meaning it is projected to rise to 2.6 per cent in 2025, and then gradually fall back to target, the latter on the basis of BoE policy still easing toward 3.5% into 2027, but a projection almost 0.5 ppt higher than previously thought.

As for the fiscal picture, public sector net borrowing is forecast to slow from 4.5 % of GDP last year to 2.1 % by 2029-30. Overall, borrowing is almost 1% of GDP a year higher on average over the forecast compared to March driven mainly by the Budget policy changes. As for the fiscal rules, the new current budget target is met two years early but by a small margin of £9.9 billion (0.3 % of GDP) in the target year. As for the new debt rule, the central forecast is that public sector net financial liabilities decrease in each of the final three years of the forecast, and fall by 0.5 % of GDP (£15.7 bn) in 2029-30, also a slim margin. However, more positively, the revised fiscal framework commits to spending reviews covering at least three years out of the forecast window, and the fiscal mandate to ultimately take effect from the third year of the forecast. This will eventually reduce the risks around meeting the Government’s fiscal targets, as the targets will be earlier in the forecast period and will encompass years for which detailed departmental spending plans have been set.