UK CPI Review: Inflation Jumps and Broadly So But Still Some Promising Wage Signs?

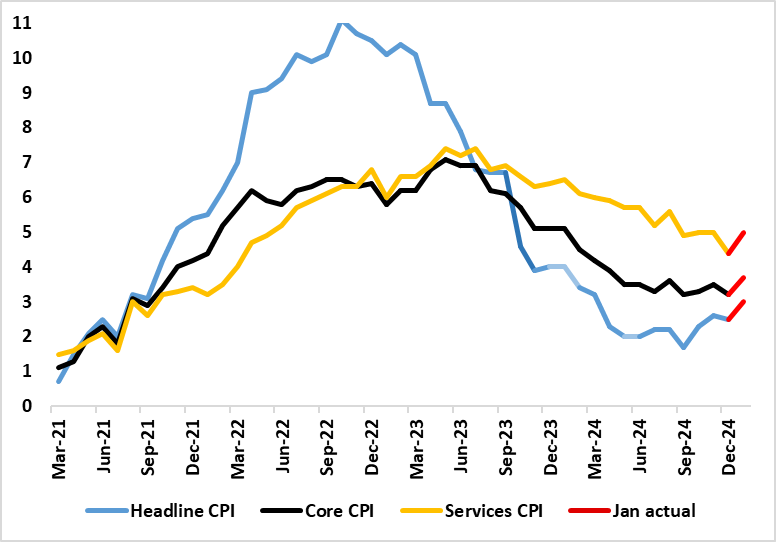

January’s CPI numbers showed a marked bounce back up, and with the 0.5 ppt rise taking it to a 10-month high of 3.0%, this being above consensus and BoE thinking. Notably services jumped from 4.4% to 5.0%, actually below expectations, having been driven higher by a swing in airfares and the rise in school fees, but with further upward pressure evident in rents too. The data add to worries about a fresh spike, albeit with it unclear the extent to which pandemic-induced changes in seasonal price patterns have acted to make the CPI backdrop much more volatile. These CPI data come after more apparently perturbing wage data, although we think that there are actually signs that companies are reacting to labor costs pressures by curbing jobs as a means of trying to raise prices. This explains out still optimistic outlook.

Figure 1: January Inflation Spikes Broadly Higher?

Source: ONS, Continuum Economics

The January jump also reflect ‘noise’ elsewhere in volatile services and higher energy inflation both due to fuel price rises (including a rise in the energy price cap) and base effects. More notably, while overall inflation may drop back in the rest of the current quarter we acknowledge that the headline will spike back higher in Q2 as a series of regulated prices (water bills) and energy costs (mainly gas) take effect. Indeed, inflation may now average around 3% in Q3, some one ppt higher than previously thought but still well below the 3.7% rate that the BoE now projects. This added price pressures are hardly demand determined and may accentuate already weak growth, thereby further restraining company pricing power. We therefore still see 3-4 more 25 bp Bank Rate cuts this year, as the BoE reacts to weaker core inflation and the added damage to demand ensuing from price spikes.

One reason for this still optimistic outlook is an alternative and more reassuring assessment of the labor market and cost pressures. To suggest that the UK labor market is merely getting less tight misses the point entirely. Amid continued reservations about the accuracy of official labor market data produced by the ONS, alternative and very clearly more authoritative data on payrolls suggest that employment is continuing to contract. Indeed, the payroll data produced by the HMRC, have now show six m/m falls since the level of payrolls peaked nine months ago. Admittedly, the drop in this five-month period is only 0.1%, but this is a marked contrast to the 1.4% increase official data suggest has occurred in the last year. More notably, overall payrolls have been buttressed by sizeable public sector employment gains to a degree that private payrolls in the last five months are down almost 100K (ie -0.5%). Moreover, amid fiscal strains, non-health public sector jobs have now started to fall too, compounding what has been an ever clearer haemorrhaging of jobs in private services, thereby suggesting that cost pressures (now accentuated by the looming increase in employee National Insurance Contributions and the actual rise in the minimum wage) have already affected the labor market severely.

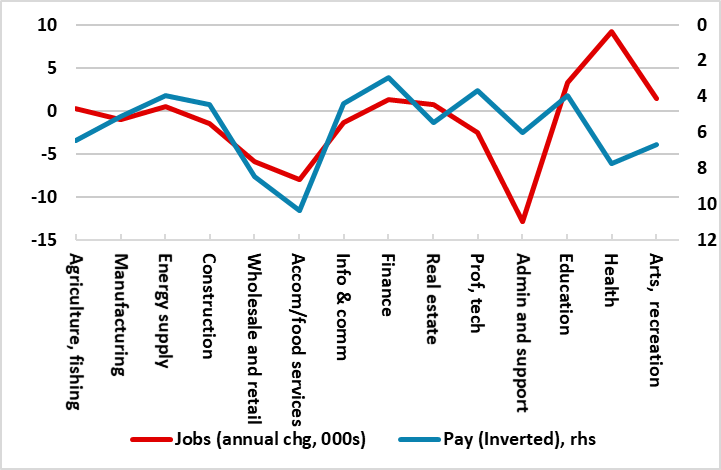

Figure 2: Sectors Facing Highest Pay Growth Already Seeing Clearest Job Shedding

Source; HMRC

Labor Market is Turning

The looming National Insurance changes taking effect in April mirrors similar moves seen of late (eg 2022, 2011 and 2003). What followed then is that labour intensive sectors and other service-based sectors reduced both headcounts and vacancies either in anticipation or immediately after the change was effective. This already seems to be happening again, but possibly as much to already rising pay bills as to the threat if even higher labor costs to come. Indeed, as Figure 2 illustrates, the labor market is working as it should do, with sectors where pay is the highest seeing falling payrolls as companies try to adjust to already high pay bills by curbing jobs to limit the rise in their labor costs that otherwise would either/both hit profit margins and/or raise the prospect of higher consumer prices. This is one the main reasons why we think he BoE is too concerned about the overall inflation outlook as (to us) we see companies are already acting to rein in their labor cost bills for fear that raising prices may only serve to reduce demand further. Indeed, as Figure 2 illustrates there is already a clear and inverse relationship between employment changes and pay growth, the exception being health where government spending initiatives are both trying to repair real pay and actual output in the sector.