UK Food Inflation; Not Just a Domestic Issue, Despite Industry Claims

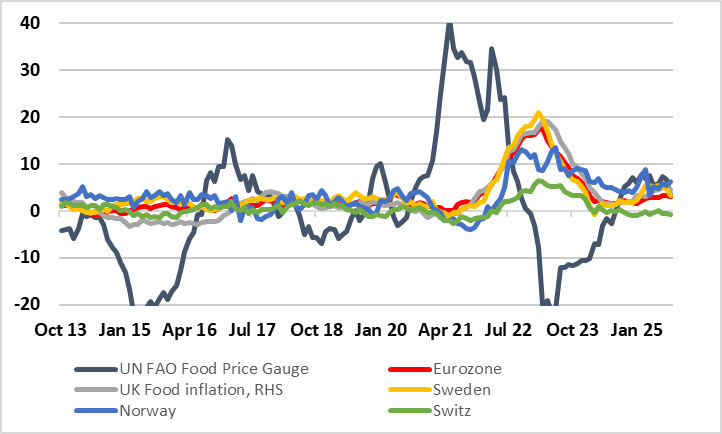

Food price inflation is becoming an increasing issue for both policy makers and households as well as companies that are generating and selling the produce. Particularly in the UK, rising food price inflation is helping shore up well-above target CPI inflation and thereby deterring the BoE from what we think is well-warranted further monetary easing. But contrary to many suggestions, not least in the UK, high(er) food price inflation is not unique to the UK (Figure 1), it very much something evident in the likes of Norway and Sweden and even some EZ economies. Moreover, there are now signs that food inflation is easing (Figure 2), the question is whether this is partly supply drive but also an indication that, despite being non-discretionary, consumers are still able and willing to shift consumption.

Figure 1. UK and Global Food Inflation

Source, UN, ONS, etc, % chg y/y

The UK food industry says domestic policies, not global pressures, are forcing food grocery bills higher, as it is alleged that food inflation in the UK outstrips that of other nearby DM economies. Living wage increases, new regulations and a backed-up planning system are among the factors apparently driving up grocery bills, according to food producers. Food inflation in the UK rose to 5.1% y/y in August, higher than in Germany, France and the US, the highest since January last year. As for the future, the food manufacturing trade body the Food and Drink Federation expects food and drink inflation to hit 5.7% by December, blaming the financial burden of government policies, such as increases to employer national insurance contributions and a new packaging tax. Meat and dairy producers, meanwhile, have sounded the alarm over rising labour costs and slowing production, warning that they and the farms that supply them are reluctant to invest in additional capacity when burdened by mounting costs, notably taxes and regulation such as the country’s backed-up planning system ch.

Across the food supply chain, supermarkets, which are among the UK’s largest employers, were taking the biggest hit from national insurance contributions changes and living wage rises, which they were forced to pass on to shoppers. Brexit has been partly blamed: when the UK left the EU, the government replaced the bloc’s subsidies with a new scheme that rewards farmers for environmentally friendly production but where the industry is paying substantial costs, for health certificates and delays at ports,

The Food and Drink Federation continues to underscore that the disparity between UK food inflation and that of peer nations revealed the cost of government regulation and policy decisions. But the data conflict with this analysis. While EZ food inflation is running at a much lower 3% annual pace, this masks divergences with the bloc which show some countries with food inflation two to three times higher. These are mainly being in the east, most susceptible to the aberration caused by the Ukraine War. But high food inflation is evident elsewhere in the likes if Norway, Sweden but very absent in Switzerland, suggesting that UK food prices are indeed more a result of global factors that domestic.

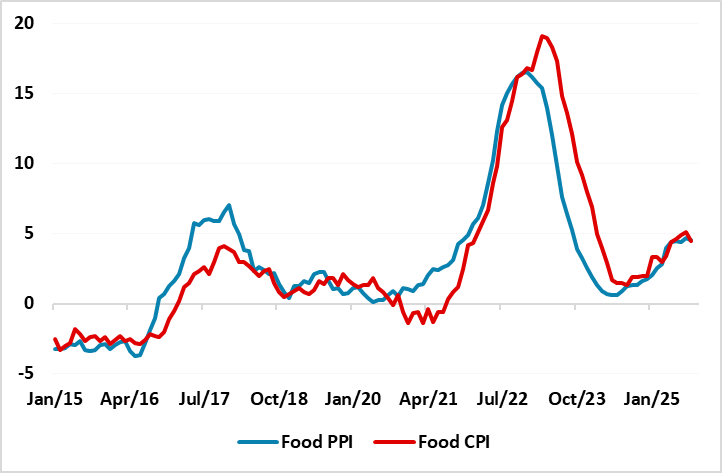

Figure 2. UK Food Inflation Slowing?

Source, ONS, etc, % chg y/y

But despite the warnings form the UK food industry about higher inflation ahead, recent news is more encouraging, both domestically and globally. As for the latter, the UN food cost index has started to softer in terms of growth rates, with three m/m drops in the last five months, this being a useful and reliable guide to UK food costs ahead. Perhaps as a result, there are already signs of softer food costs pressures in the UK, these ranging from softer producer price (PPI) food inflation and to survey data from the BRC which have just seen the largest m/m fall in food cost (mainly non-fresh) in over five years. And official CPI data seem to be flowing suit with a surprise slowing in September due to weaker cereal and vegetable costs. Given the dry weather through the summer, we would be reluctant to suggest that a turn has occurred, but the data do suggest that whatever the industry may be saying, weak demand is having an impact. While food is non-discretionary, that does not stop consumers shifting consumption in pursuit of lower costs as their spending power is frayed.

I,Andrew Wroblewski, the Senior Economist Western Europe declare that the views expressed herein are mine and are clear, fair and not misleading at the time of publication. They have not been influenced by any relationship, either a personal relationship of mine or a relationship of the firm, to any entity described or referred to herein nor to any client of Continuum Economics nor has any inducement been received in relation to those views. I further declare that in the preparation and publication of this report I have at all times followed all relevant Continuum Economics compliance protocols including those reasonably seeking to prevent the receipt or misuse of material non-public information.