U.S. Immigration Slowdown and the Labor Market

Overall, slower illegal and legal immigration will likely slow employment growth and curtail the rise in the unemployment rate from the U.S. economic slowdown. More older workers or an increase in the percentage of female workers would help, but are not a priority for the Trump administration and the low 60% U.S. employment rate is unlikely to significantly rise.

While the Trump administration tariff and 10yr budget bill have been the main focus for financial markets, slowing immigration should also be watched as well for employment growth and labor market conditions.

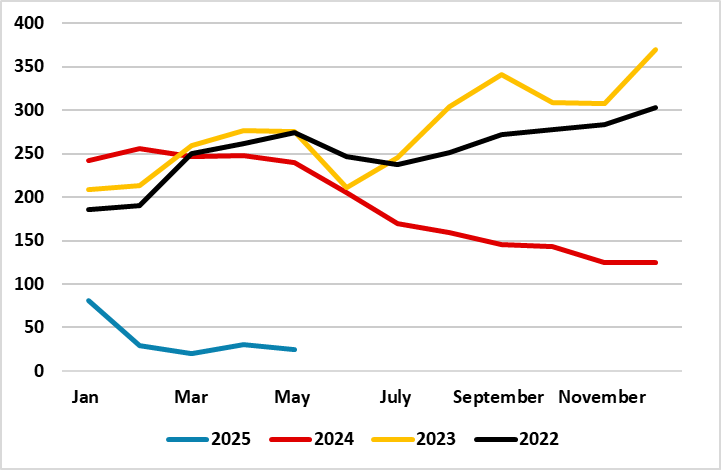

Figure 1: Monthly Encounters of U.S. Immigration Services (Thousands)

Source: U.S. Border Control (Border control and Office of Field Operations Combined)

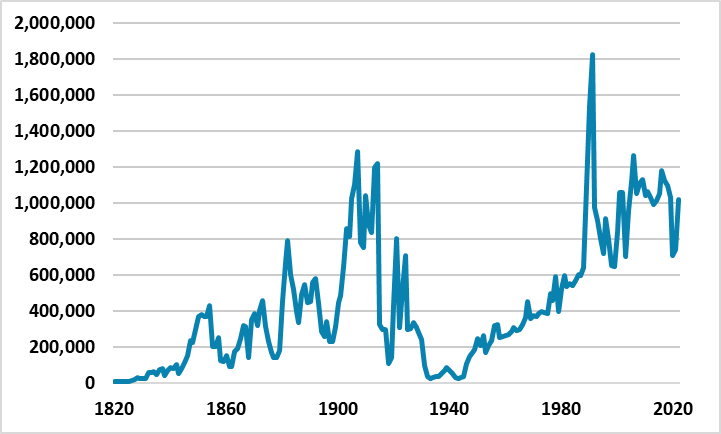

The U.S. immigration service has seen a collapse in the number of illegal immigrants entering the U.S. using the U.S. Borders Control data (Figure 1), which is all the more dramatic versus the post COVID surge seen in 2022. Meanwhile, legal immigration into the U.S. is also reported to have slowed in 2025, which largely reflects global workers or university students being less interested in moving to the U.S. Though the Trump administration is not trying to return to the days of the 1930/40’s of ultra-low legal immigration (Figure 2), lower global demand for legal immigration could last through the Trump administration. U.S. labor supply growth will thus slow due to lower illegal and legal migration, which would impact employment growth and potentially consumption. Can more of the existing U.S. population join the workforce to help labor market supply?

Figure 2: Legal Immigration into U.S. (Yearly)

Source: U.S. immigration Service

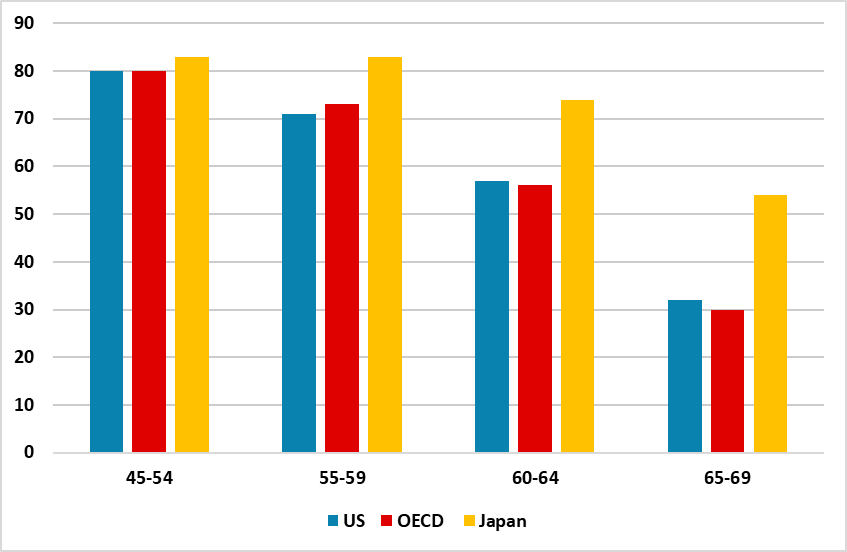

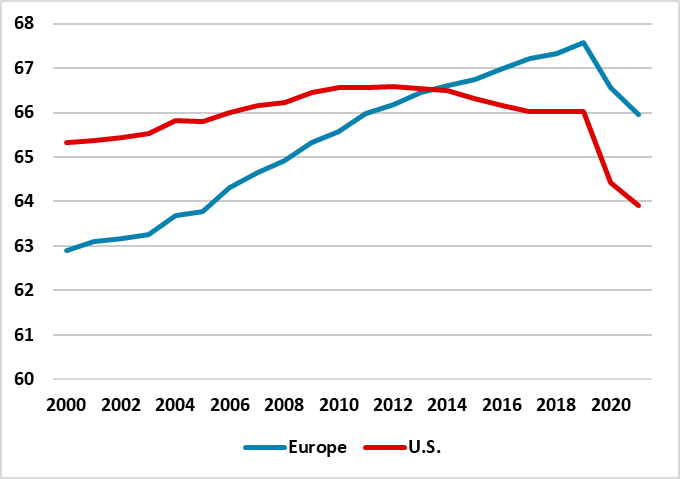

The good news is that the U.S. population and labor market is still growing in absolute terms in contrast to the EU or Japan. This will deliver a natural increase in absolute employment in the coming years. However, this could be added to if the employment rate of the population is lifted. This could be achieved in theory being getting more old people or women to take advantage of working opportunities and join the labor force, which could boost the employment rate from the current soft 60% to 62-65% seen in the pre GFC period. However, lifting the percentage of 55-64yr and 65-69yr old working in the U.S. will be difficult, as they are already better than the OECD average (Figure 3). Japan high reading reflect a different structural in the labor market where companies prizes old workers and part time/flexible working. Additionally, the U.S. has poorer health for the over 55’s compared to other DM economies (Figure 4), as high U.S. health expenditure is not effective at improving health outcomes for the population as a whole and the obesity crisis is worse than other DM economies. This means people in their 60’s can find it difficult to take up new jobs for health reasons. Finally, male employment the U.S. also suffer a problem from lower employment rates for men that have been in prison versus those that have not, with 1.8mln currently in prison and ex-felons having an above average unemployment rate.

Figure 3: Employment Rate by Age Group (%)

Source: OECD

Figure 4: Healthy Life Expectancy (Years)

Source: WHO

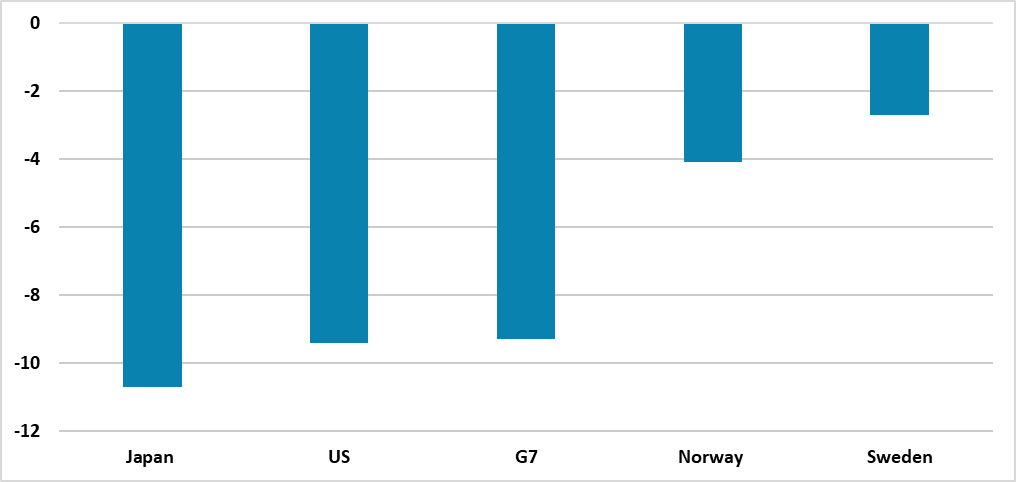

The other main alternative is to encourage more women to join the workforce and lift female employment rates towards male employment rates. Nordic countries gap between male and female employment rate is much lower than the U.S. or the G7 average (Figure 5). However, this has been achieved in Nordic countries due to universal childcare and employers that are active supporters or part time and career breaks. These microeconomic policies are not however a priority for the Trump administration and thus the U.S. labor market cannot count of this filling momentum from slowing migration.

Figure 5: Difference Female and Male Employment Rates (%)

Source: OECD

Overall, slower illegal and legal immigration will likely slow employment growth and curtail the rise in the unemployment rate from the U.S. economic slowdown. More older workers or an increase in the percentage of female workers would help, but are not a priority for the Trump administration and the low 60% U.S. employment rate is unlikely to significantly rise.