UK GDP Preview (Sep 11): More Mixed Messages Ahead as Fiscal Updates Looms

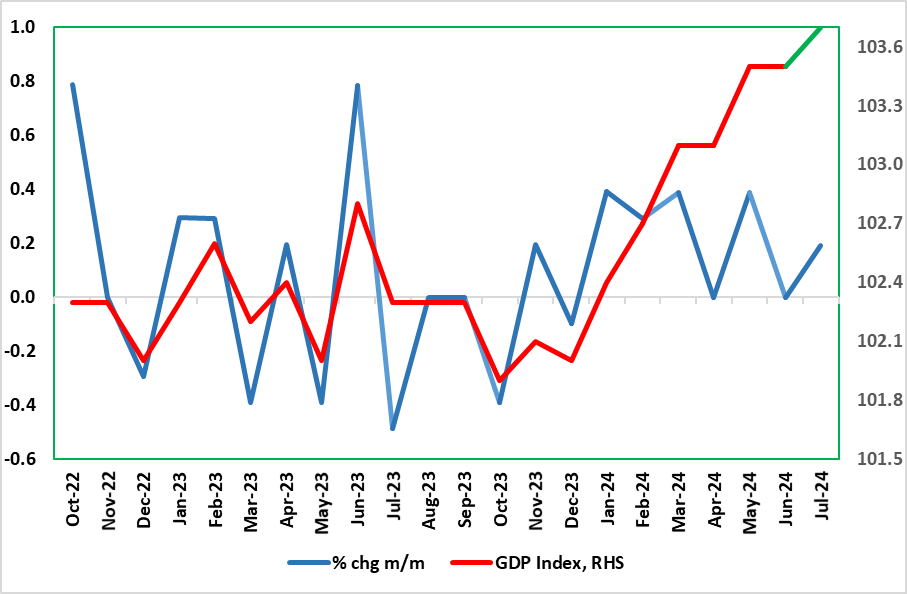

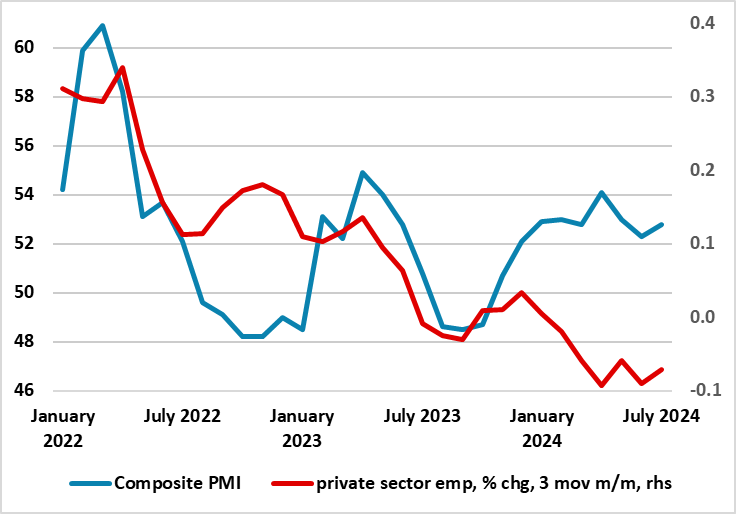

It does seem as if the economy is going to show more positive signs with the July GDP data. Indeed, we see a 0.2% m/m rise, albeit with the data still showing volatility. Indeed, GDP growth has been positive in only one of the three months of the last quarter, having been flat in June. Regardless, amid a small rise in retail sales and car production data, GDP does seem destined for a fresh rise (Figure 1), but where the June lack of growth in June has created a soft base effect for Q3 growth which we see advancing just 0.1%, a quarter of the BoE estimate. This weaker immediate outlook is something that chimes more with labor market and public borrowing data and where HMRC payrolls paint a much softer backdrop and possible outlook that also conflicts very much with PMI survey numbers (Figure 2). Indeed, it could be argued that the labor market data due Sep 10 may have more impact on BoE thinking, albeit with the anticipated marked drop in average earning growth we envisage being something the MPC also expected.

Figure 1: Volatile But Clear(er) Recovery?

Source: ONS, green is CE estimate

After the mild recession in H2 last year, the ‘recovery’ now evident is much clearer than any expected with GDP growth notably positive but in only one of the three months of the last quarter. Indeed, amid weaker retail sales, property transactions and car production data, GDP failed to grow in June. But this still left Q2 GDP numbers (released alongside the monthly data) showing a 0.6% q/q rise after the 0.7% gain in Q1. That Q1 ‘strength’ was partly due to a further fall in imports, but that was not be the case in the Q2 breakdown, albeit with consumer spending softening, with growth instead boosted by an import-fueled jump in stock-building.

Regardless, the H1 GDP data is too historic to have any major impact on BoE thinking. As for Q2, on the supply side, as suggested above, the economy was boosted mainly by services with manufacturing contracting (in spite of a clear June bounce), this divergence being something very much evident across W Europe. Consumer spending growth halved to 0,2% while business investment slipped slightly, with domestic demand instead boost by government spending – hardly likely to persist. Unlike the Q1 GDP jump, imports actually detracted from GDP, but this import build spilled over into an inventory rise which also may not persist. Even so, the Q2 jump actually saw little growth in the quarter, instead boosted by base effects from Q1

Regardless, these national account data have prompted BoE thinking to be much more positive and make it now suggest growth of around 1.25% for the whole year, more than double the previous estimate, albeit we think a little too optimistic. Our reticence reflects that this apparent resilience, if not strength, in the GDP data contrasts increasingly with employment weakness and is partly a result of public sector gains. But the strength in GDP is chiming with PMI survey data and this resonates with the BoE, even though those PMI data (covering the private sector) also conflict with what (possibly more) authoritative private sector payroll suggest (Figure 2).

Figure 2: PMI Strength Conflicts with Payroll Weakness

Source: ONS, CE

Regardless, the economic backdrop will obviously be important for the Chancellor as she crafts her Budget due on Oct 30. Very much her aim is to lift (trend) growth, but it is unlikely that the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) can make any upgrade to its economic outlook purely on the basis of government aspirations. In any case, the OBR already has a very upbeat GDP outlook built into its fiscal projections, with GDP growth of around 2% in both 2025 and 2026, numbers well above current consensus thinking. The OBR may have to revise up its 2024 projection as its current estimate is slightly below the 1% we and the majority are envisaging. But the OBR too may have reservations about the growth backdrop, noting that the more recent monthly public borrowing numbers are actually higher than it expected despite the apparent GDP strength.

Indeed, central government borrowing (perhaps a better underlying gauge) is already overshooting by £10bn just one-third of the way through the fiscal year), something that partly validates the government’s claim about a fiscal hole. Indeed, the question may be just how much there are possibly significant upside risks to the OBR borrowing projections, not least from above-inflation public sector pay rises.