India's Industrial Chill: 2.9 % Growth Signals Cooling Engines

India’s factory growth hit the brakes in February, with industrial production rising just 2.9 %, half January’s pace and the slowest since August 2024. Manufacturing and mining lost traction, while a small pickup in electricity output provided limited relief. Stalling consumer‑goods output and patchy retail sales point to cooling domestic demand—pressures that could deepen if new US tariffs squeeze exports and sentiment. Policy support is on the way: back‑to‑back RBI rate cuts and higher income‑tax thresholds promise cheaper credit and extra cash in households’ hands, while rural markets remain relatively resilient. Yet the rebound hinges on smooth rate transmission, a friendly monsoon and calmer global conditions; otherwise, weak demand and external shocks could keep industrial momentum subdued well into FY26.

India’s factory engine lost steam in February, with the Index of Industrial Production (IIP) expanding just 2.9 % yr/yr —barely half the 5.0 % pace logged in January and the weakest showing in six months. The out‑turn undershot private‑sector forecasts of 3.6 – 4 %, highlighting how fragile the post‑pandemic rebound has become as both external and domestic headwinds gather force.

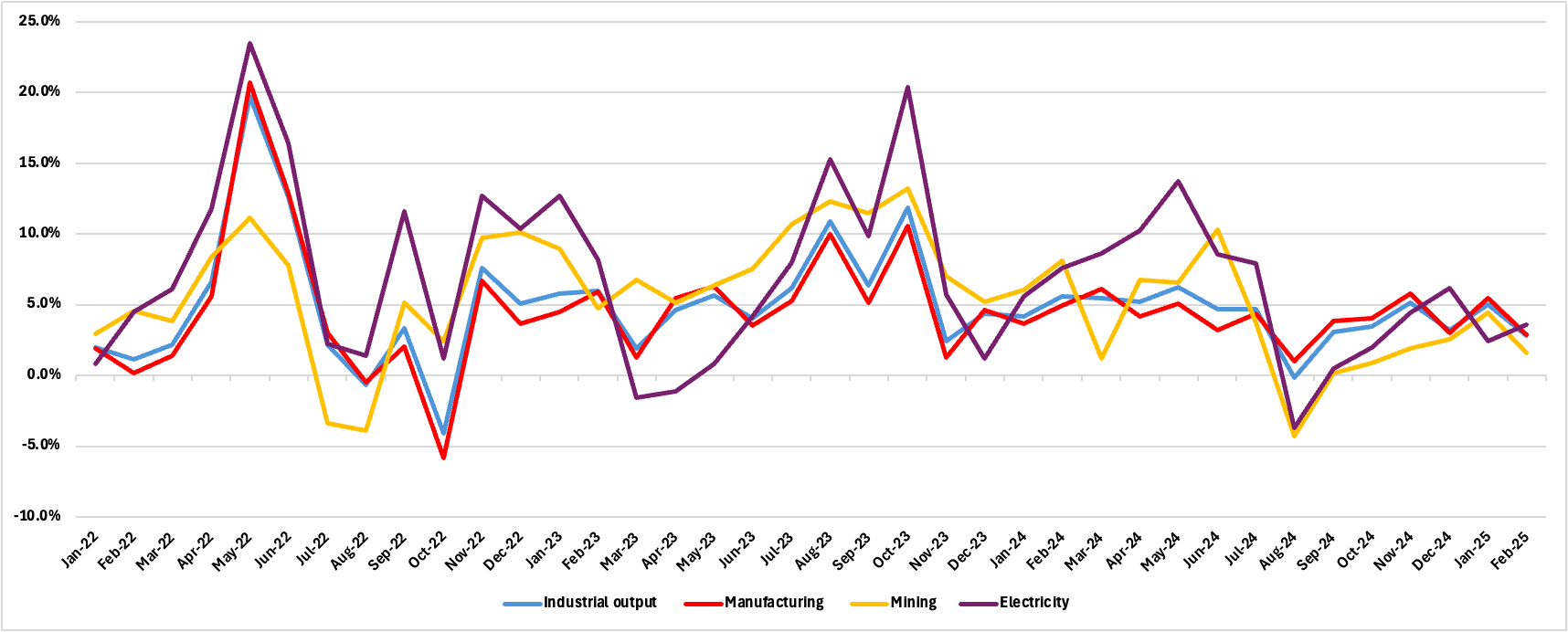

Figure 1: India Industrial Output (% yr/yr)

Source: Continuum Economics

Manufacturing, which carries a three‑quarter weight in the IIP basket, slowed to 2.9 % yr/yr in Feb from 5.5% yr/yr in Jan, while mining growth almost stalled at 1.6 % (January: 4.4 %). Electricity generation offered a modest offset, rising 3.6 % versus 2.4 % a month earlier, though output is expected to climb further as peak‑summer demand kicks in.

Under the bonnet, the picture is mixed. Fourteen of 23 manufacturing groups still posted gains: basic metals rose 5.8 % on the back of stronger alloy‑steel and pipe production; motor vehicles jumped 8.9 % thanks to demand for commercial vehicles and components; and non‑metallic mineral products—largely cement—advanced 8.0 %, underscoring the government’s infrastructure push. Yet pockets of strain are evident: consumer non‑durables contracted 2.1 % and intermediate goods barely grew, signalling weak pipeline orders.

User‑based data tell the same story. Capital‑goods output climbed a healthy 8.2 %, and infrastructure goods 6.6 %, but consumer durables eked out 3.8 % and the discretionary non‑durables slump points to tepid household demand.

Those demand‑side cracks are already visible on the high street. Retailers report that January–March sales cooled sharply outside festival periods: food and grocery tick along, yet apparel is flat and electronics rely on one‑off launches or cricket‑season boosts. Industry executives blame stock‑market volatility, high rental inflation and tighter rules on unsecured lending for dampening sentiment—factors that could intensify if forthcoming US tariffs squeeze margins or trigger job cuts in export‑oriented sectors.

Indeed, Washington’s reciprocal duties on Indian imports add a fresh layer of uncertainty. While a diversion of orders away from China may cushion a few niche manufacturers, wider fallout—costlier inputs, delayed investment and softer global demand—could outweigh any near‑term gains, capping industrial momentum just as domestic consumption wobbles.

For now, macro‑policy is turning more supportive. The Reserve Bank of India has followed February’s surprise easing with a second 25‑basis‑point cut, pulling the repo rate to 6 % and adopting an “accommodative” stance. Lower borrowing costs should filter through to vehicle and white‑goods finance, while the Union Budget’s decision to lift the income‑tax exemption limit to INR 700,000 injects extra liquidity from mid‑FY26. Rural demand, already buoyed by decent rabi prospects and social‑transfer schemes, remains a relative bright spot.

Cooling inflation provides room to manoeuvre: headline CPI sank to 3.3% yr/yr in March, helped by a broad correction in vegetable prices and three‑year‑low crude oil prices. Further disinflation could spur additional monetary easing if growth disappoints.

Even so, the path to strong growth is far from assured. Tariff‑induced supply‑chain shifts threaten export volumes and imported inflation. Transmission of rate cuts could stall if banks, facing tight liquidity and rising risk weights, fail to pass on cheaper credit. Weather poses another wildcard: an erratic monsoon would quickly reignite food inflation, compressing real incomes just as households start to re‑lever.

We anticipate industrial growth to limp through Q1‑FY26 before re‑accelerating in the second quarter, once tax rebates land in pay packets, rate cuts feed through, and festival demand picks up. Infrastructure and construction goods—underpinned by public capex and housing—should remain sturdy, and capital‑goods orders may improve if corporate balance sheets strengthen. Conversely, consumer‑facing manufacturers could endure a longer slog unless confidence rebounds strongly.

In short, February’s IIP print is a reminder that India’s post‑pandemic upswing is not immune to global shocks or softening domestic demand. Policy support is arriving, but its effectiveness will hinge on quick transmission, a favourable monsoon and—crucially—how the looming tariff skirmish plays out.