Eurozone Outlook: Trump, Tariffs and the Possible Trade Tremor

· Once again, it does seem as if EZ activity expectations are being pared back in line with our below consensus thinking, most notably for next year. The result is that while the economy has been growing afresh it is doing so timidly, with downside risks persisting more clearly into 2025 as some such risks may be materializing as effectively sizeable downgrades in ECB growth projections suggest.

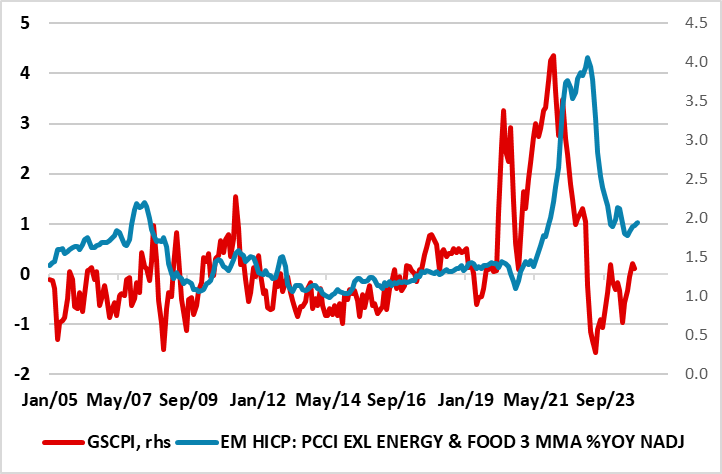

· This makes us more confident regarding our long-standing and still-below consensus HICP outlook in which headline inflation is seen easing below target durably in H1 next year and then staying there, with the core rate (still worrying the ECB) likely to follow. This picture has persuaded the ECB to speed up its easing and we forecast more cuts (ie 100 bp) to follow in 2025 and maybe more.

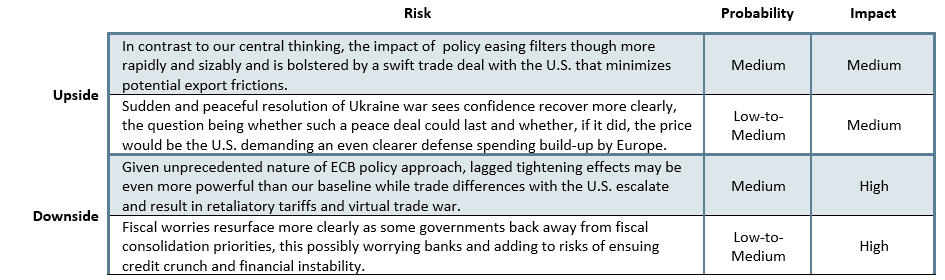

· A banking crisis is still a low to modest risk save for a possible fresh fiscal flare-up. Perhaps the main risk is around fiscal policy, it either inhibiting growth and/or triggering financial instability. In addition, global growth could disappoint further, not least given the added uncertainty posted by the threat of a trade war.·

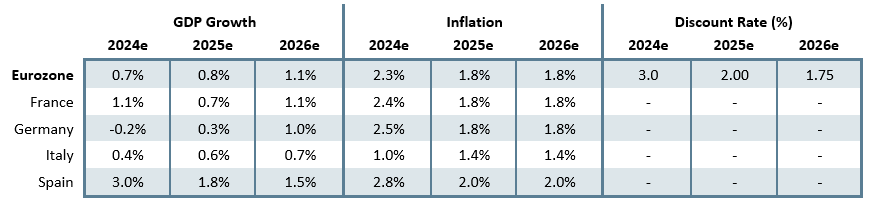

· Forecast changes: Compared to the last outlook, we have largely downgraded the overall EZ growth outlook, with a slightly less-fragile recovery for 2024 but even clearer below trend-type growth in 2025 and may be now also 2026. More notable, is the hardly-revised and still-soft EZ HICP inflation outlook in which the target is undershot on a sustained basis into 2025 and beyond. As a result, we have revised our ECB policy rate forecasts to show both faster and greater easing.

Our Forecasts

Source: Continuum Economics, Eurostat

Risks to Our Views

Source: Continuum Economics

Eurozone: Grey(er) Clouds Forming

It is not all gloom in the EZ. There have been some brighter consumer signs seen of late with the possibility that the recent, fresh rise in household savings reverses and thus may sustain this recovery into 2025 and beyond, helped by a recovering housing market. But, on the whole, the EZ economy is facing clear downside which may now be materializing. The fact that growth rates among the EZ main economies have diverged even further of late (Spain robust, Germany possibly contracting afresh) actually reflects a marked disparity in growth rates between hitherto strong services and persisting declines in goods output, this evident in both survey data as well as official national account data. But recent survey and now official output data are increasingly suggesting weaker activity, now embracing weaker services to a degree that imply that the support the sector has given the whole EZ economy so far this year may have dissipated, if not reversed. Indeed, GDP growth could even be negative this quarter. At this juncture we still think this will be a blip rather than a fresh and weaker trend but is nevertheless indicative of the weak underlying growth picture we have been flagging for some time. Indeed, while recent better than expected numbers have led us to upgrade the 2024 GDP outlook by a notch - but still to a below consensus 0.7% - we have pared back the 2025 outlook by a further 0.2 pp to a similar 0.8%, both even more clearly below par and mainstream thinking. The question is whether such weakness persists into 2026. As for the latter we see ‘only’ 1.1% GDP growth, the question being whether the weakness in capex we see continuing means this is no more than (weaker than previously assumed) potential.

Indeed, over and beyond what may have been a recent and possibly largely involuntary inventory build, this also involves contracting overall capex that may continue next year. Tight financial conditions (still very much evident in weak private sector credit and deposits) are one cause of the capex weakness, accentuated by still wary company thinking and banking sector reservations about lending. Banking reluctance to lend is also a continued cause. But increasingly is uncertainty emanating very much from political divides and policy paralysis in several countries (clearly Germany and France) but also now worries about external trade emanating from the U.S. This outlook may have been made worse by what may be greater fiscal consolidation measures from several countries that will continue beyond next year.

In regard to trade issues, and given his repeated boast that he is fundamentally a dealmaker, it is likely that the EU riposte to president-elect Trump’s tariff threats will be not to retaliate, but to negotiate as was the case in Trump’s first term. In light of the EU’s sizeable trade surplus with the US, this will involve offering to buy more US goods (and services); the EU has already suggested buying more US energy, military and agricultural goods as a concession, even though the latter may be somewhat contentious. But this will surely occur only alongside signals of clear preparations and a willingness to retaliate if needed if punitive tariffs materialize. There would be some positive spill-over as importing more US liquefied natural gas would help the EU finally to ban remaining Russian LNG imports. Meanwhile, Europe will need US-made weaponry, too, it takes on more of the burden of defending Ukraine, this also likely to be a demand from Trump for Europe to boost its defense programs if NATO is to stay together. Indeed, there are suggestions that European members are considering the 2030 target for defense spending by a full ppt to 3% of GDP at its annual summit next June, a move that would put intense pressure on already strained national fiscal positions.

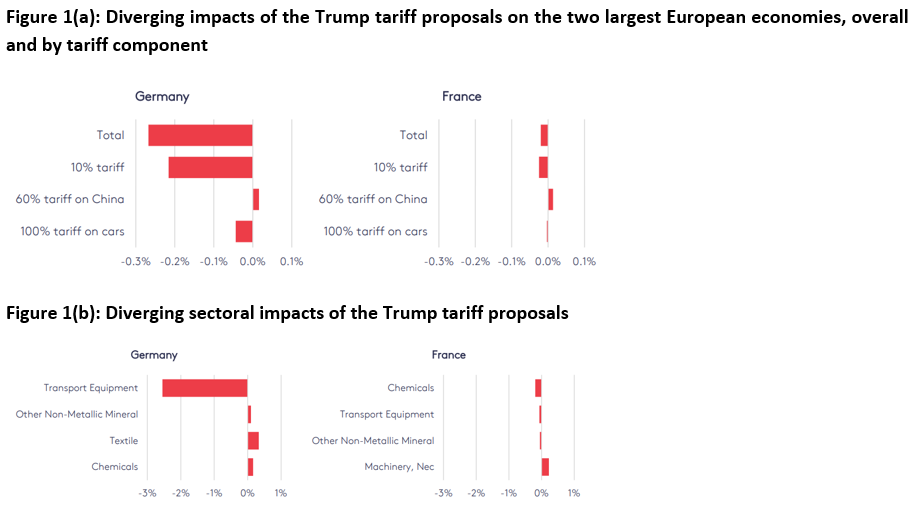

As for the impact, this is obviously hard to judge given the lack if details and timetable. But work has been done to model some likely effects such as that recently by the London School of Economics. This very clear concludes that the proposed tariffs would hit GDP in the United States by -0.64% and in China by -0.68%, while the European Union would face a more modest reduction of -0.11%. Within Europe (Figure 1), the impacts would vary significantly: Germany could see a -0.23% drop in GDP, while in Italy the decrease could be negligible and hardly much worse for France. Certain European sectors, particularly Germany’s automobile exports, would be disproportionately affected and may require targeted protective measures. But importantly, the research suggests that retaliatory measures by China and/or the EU would likely worsen economic outcomes for all parties involved, potentially sparking a damaging trade war. In terms of our forecast the impact could be much more sizeable, depending on how confidence is hit with it unclear as much as to when the main risk should be for 2025 or 2026. At this juncture we consider the downside from actual tariffs as a risk than reality, but (as suggested above) cannot ignore the likely sustained impact of uncertainty weighing on activity into 2026.

Otherwise, the anticipated cyclical, and possibly structural, recovery in imports into 2025 as well as what may be a weak global economy weighing on exports will also mean that the improvement in the current account surplus this year (at almost 2.5% of GDP) may not improve any further next year or in 2026. This is also a headwind to GDP growth.

Source: London School of Economics

Amid what has been a disinflation process so far very much supply driven, but encompassing what has already been a marked softening underlying inflation, we still envisage headline HICP moving below 2% more durably next year with the core not far behind and then remaining below through 2026. This picture is little changed compared to the previous Outlook, but encompasses evidence of softer cost pressures. Indeed, the omens point to services inflation slowing in due course, something we think will emerge more visibly into 2025 as wage growth slows to pace consistent with the inflation remit.

Fiscally, the EZ stance is estimated to have tightened significantly in 2024 on account of the withdrawal of a large part of the energy and inflation support measures, as well as strong revenue developments in some countries on account of composition effects, among other factors. The fiscal stance is projected to continue tightening, but only slightly over 2025-26 when spending funded by NGEU grants should be phased out – however the fiscal policy assumptions are surrounded by uncertainty. But as the headline EZ budget gap may fall to around 3% of GDP this year from 3.6% last year (similar to that thought three months ago) but will not any drop further into 2025 without more consolidation measures which do seem to be under active consideration, possibly pressured by new EU fiscal rules. Thus, with headline budget gaps that may stay around 3% of GDP into 2026, the fall in the EZ government debt ratio to 88.5% of GDP last year will likely soon be followed by a rise.

Figure 2: ECB Sees Most Measures of Underlying Inflation Settling Around Target?

Source: ECB Persistent and Common Component of Inflation, NY Fed’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index

ECB: Clearly Flagging An End to Policy Restriction

A fourth 25 bp discount rate cut at this month’s Council meeting, to 3%, was also the third in a row. But this month’s meeting was important for the (as we expected) change in forward guidance in which the ECB now accepts that on-target inflation is likely to be durable enough so that it no longer has to pursue policy restriction. In this regard, the first glimpse of 2027 economic projections support this as they point to a second successive year of around-target inflation even on a core basis and also on the basis of markets assuming rates fall to around 2% in 2026 – hence, the ECB is largely endorsing such market thinking, showing just how much it has been forced to reassess in recent months.

But the dominant ECB issue now is the extent to which downside growth risks have turned into reality with it clear that growth worries have risen. Indeed, preserving growth does seem to have become the ECB policy priority, not least against a backdrop of weak business survey data as firms are holding back investment spending in the face of weak demand and a highly uncertain outlook. Moreover, these downside risks have other aspects, equally worrying, especially as (even according to its own recent Financial Stability Review), they could fan financial instability issues, the latter already building in France’s ever clearer political impasse and policy vacuum. They are also accentuating the disinflation outlook enough to have made the ECB now admit that most measures of underlying inflation suggest that inflation will settle at around target. With this in mind, the ECB has to ask itself whether such soft inflation signals are not just an indication of the target being met early and durably but are as much a further symptom of economic weakness about which it has been overly complacent.

Amid what has been faster easing, the ECB must be considering what neutral policy and we think the implies around four 25 bp cuts in H1 next year, with an ensuing around-neutral 2% policy rate. But it is possible that amid a continued sub-par growth outlook into 2026, then further easing may be on the cards into 2026.

Germany: Even More Headwinds?

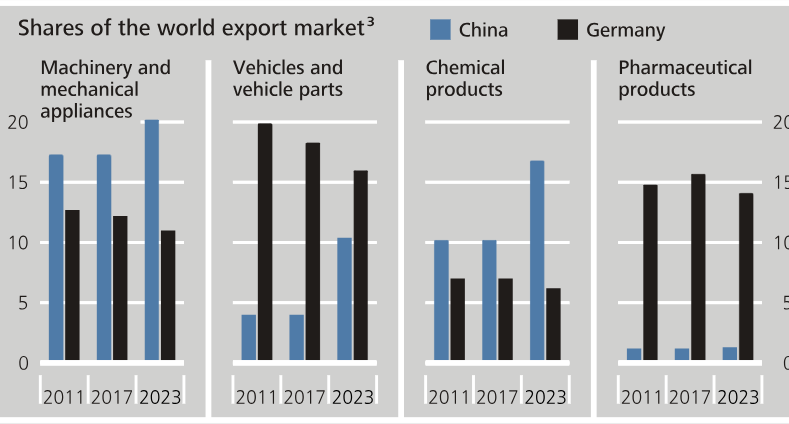

We have highlighted repeatedly the structural factors increasingly affecting the economy, do a degree to stress that Germany’s economic malaise is far from purely a cyclical development. But these factors seem to be multiplying, with the threat that the growing competiveness losses to China (Figure 3) may now be compounded by US trade tariffs and/or protectionism. In addition, the economic malaise that has resulted already has led to the break-up of the government collation that was increasingly divided not least about the source and solution of Germany’s problems. An early general election is now scheduled for February 23 and where the current opposition CDU are almost certain to take power, albeit probably in coalition with the Greens and even possibly the Social Democrats. This implies that policy making impetus may be difficult given divides, but one positive is that some fiscal stimulus may be prioritized with room provided by a modification to the so-called debt brake, something even the traditionally fiscal cautious Bundesbank considers sensible. All of which could mean that a budget gap set to fall below 2% of GDP in 2025 could well be somewhat higher and remain there into 2026, but where this would still keep the debt ratio around the current 63% of GDP over this period. There is plenty on the possible fiscal agenda; the Federation of German Industries estimates that Germany needs to invest 1.4 tn by 2030 to bolster its ever-creaking industrial base.

Indeed, Germany may have re-entered mild recession – we have more than halved next year’s growth down to 0.3%. Domestic demand is set to pick up but only slowly into 2025, as real wage growth returns. Even so, consumer spending is growing very slowly but just outpacing that for GDP into 2025 even as the near 10% current fall in house prices both erodes household wealth and puts added upward pressure on rents. However, investment growth is projected to remain well below pre-pandemic levels, constrained by still-high financing costs and uncertainty. Most notably, the biggest damage is that still emanating from the slumping construction sector.

Exports will remain sluggish in 2025, the question being how and when Trump trade policies bite. But whatever is agreed (or not) Germany is the most exposed (Figure 1). There is also the import side, as pressure to buy US defense and energy products will also damage the current account, albeit where a surplus of well over 6% of GDP this year may drop by less than a ppt into 2026

Figure 3: German Competitiveness Being Hit by China

Source: Bundesbank, all in relation to World Customs Organization Harmonized Item Description and Coding System

France: A Political Crisis But Not (Yet) a Fiscal One

With an ever clearer divided parliament having toppled ex-PM Barnier’s fledgling administration convincingly, France now has no effective government and instead faces dysfunction even with a new PM at the helm. This far from unexpected development is a deeper political crisis and one that even without the fiscal cuts that the failed Budget envisaged is likely to mean that the country also faces an increasing economic predicament. But with President Macron able to use so-called ‘special powers’ to fund the government for the time being, and with an effective political truce being encouraged, France does not (yet) face a fiscal crisis. But France still faces a tighter fiscal stance into 2025. Indeed, special powers which involve rolling over the 2024 budget will increase effective tax-takes due to a lack of indexing while holding government spending constant in nominal terms implies clear real-term cuts.

Admittedly, it is unclear what this may mean for the budget deficit, but with it likely that debt servicing costs will have to rise, the fiscal hole in the coming year is unlikely to be much different to the circa-6% of GDP gap seen for this year and thus far above the 5% goal of the Barnier Budget plan, let alone European Commission goals.

Regardless, prolonged political deadlock is likely to continue being the order of the day as Macron is likely to resist pressure to call an early presidential election before his term ends in 2027. Indeed, forming any stable and even minority administration is going to remain complicated as the three main parliamentary factions are all being driven by that looming election. However, not only it is likely that France may remain in a political impasse until at least next July when new parliamentary elections can possibly take place, but with the electorate also very much sectioned into three factions, a stable government being voted in at that juncture even then is unlikely! All of which suggests a fiscal crisis and/or crunch, which may be avoidable for the time being, could occur in H2 next year or even into 2026.

As a result, with little chance of passing difficult structural and fiscal reforms, already-growing debt sustainability questions look even worse as the debt ratio looks set to rise by over one ppt per year from the 110% set in 2023 and only partly due to higher debt servicing costs which may rise some one ppt into 2026 from the current 1.9% of GDP; the pass-through of higher borrowing costs will be gradual because the French government's debt is long dated, with the average maturity longer than 8.5 years.

Indeed, encompassing a persistent structural gap, budget deficits may average at least 5% of GDP out to 2026, with the risks that real economy fall-out creates a vicious circle due to the need to make ever larger fiscal consolidation measures to suppress growing market jitters. The now emerging headwinds have actually not prevented any downgrade to this year’s forecast to 1.1% but solely due to higher than expected government spending and weak imports– the recent Olympics cause a positive blip last quarter but one that may be largely reversed in Q4!

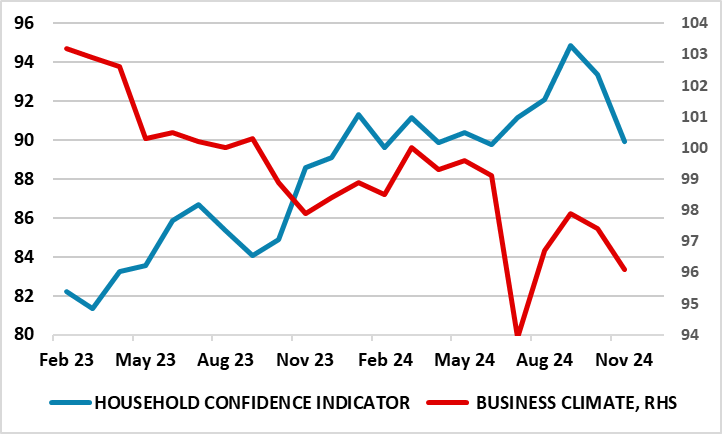

But we have pared back the 2025 outlook both a result of the implicit fiscal tightening alluded to above but also to the other repercussion of the political impasse, namely now clearly softening (ie below-par) messages from the various business and consumer surveys (Figure 4). We now see a 2025 growth picture of 0.7%%, 0.3 ppt lower than forecast three months ago. Notably, private consumption will be weak as those energy support measures are fully reversed into 2025 and as high savings remain locked up in illiquid assets and as in 2024 may grow less than overall GDP. So the boost will be modest and consumer spending will grow no more in 2025 than overall GDP, this also the case for 2026. Investment is projected to recover progressively into 2026 but only after possible fresh drops in coming quarters as uncertainty dominates. Meanwhile, over the forecast horizon, net exports are set to have a minimal contribution to growth, the question being whether imports again act to bolster GDP through 2025. One positive is that France is relatively insulated from any US trade flare-up, and could actually be a beneficiary if hefty tariffs are levied on China (Figure 1).

However, this soft growth outlook will reinforce the broad disinflation already very much evident. Thus we still envisage CPI inflation at 1.8% next year down from this year (to 2.4%) and likely to stay under 2% through 2026, albeit with risks on the upside from possible fiscal measures. This inflation picture will not help the fiscal side and reflects a continued reining in pricing power and a rise in the unemployment rate back above 7.5% through 2025 and perhaps 2026 and where companies are likely to see profit margins fall further - a number of French companies have recently announced lay-off plans that amount to thousands of job losses!

Figure 4: France – Both Consumers and Companies Getting Gloomier

Source: INSEE, % balances

Italy: Can the Consumer Rebound?

Italy is unlikely to be major victim of any US trade restrictions in the coming two years, save for some damage to its transport sector. Indeed, it could even benefit on competitiveness grounds should China face a 60% tariff. But the outlook is still sobering. We have downgraded the 2024 backdrop by 0.3 ppt to 0.4% and that for 2025 by a notch to a not-much better 0.6%, with the early sighter for 2026 picking up only a little further, projections that very much square with current business survey data. Crucial in this outlook is the consumer, where spending this year may even have sunk slightly, partly due to restrictive financial conditions and the wind-down of the Superbonus building tax credit (a generous tax incentive for housing renovation, which should be entirely phased out by next year). But both factors should ease through 2025 and amid what has been a still-falling jobless rate and actual real wage growth (nominal gains of around 3% are seen again in 2025), the consumer should bounce back – something likely 1% gains are possible in both the coming two years, even given CPI inflation picking up slightly to 1.4% this next year and into 2026. The question is whether this recovery will fuel a pick-up in imports, the weakness in which is actually the main factor that will allow a positive GDP reading. Admittedly, exports may also recover into 2026, but nothing major is anticipated given the weakness in key neighbouring economies, most notably Germany. As a result, we see the current account surplus staying just over 1% of GDP in the coming two years.

We still consider that the main downside risk is that the wind-down of the Superbonus triggers a larger and more persistent contraction in housing investment, the latter having been a key source of growth over 2021-23. But on the upside, the acceleration in public investment related to the National Recovery and Resilience Plan could boost growth in 2025-26 more than expected, not least as that a full utilization of New Generation EU funds implies that such-related spending needs to be ramped up from about 1% of GDP in 2024 to about 2½ per cent of GDP on average over 2025-26.

As was the case three months ago, fiscal worries seem contained, at least that is the message from the circa-30 bp fall in sovereign spreads vs Germany at a 10-year horizon compared to the last Outlook. Partly this reflects genuine fiscal improvements, albeit largely a one-off result of the unwind the Superbonus scheme. However, the primary balance may have moved into a small surplus this year and may turn more positive in 2025 (around 0.5% if GDP). But while this may still see budget deficits of around 4% of GDP persisting this year and next (some one ppt lower than envisaged three months ago), upside risks persist not least given a structural gap of over 5%. Indeed, the European Commission warn that even into 2026, with budget deficit down to 2.9% of GDP and a primary surplus of 1.1% of GDP a continued rise interest expenditure to 4% of GDP will mean that after declining to 134.8% of GDP in 2023, close to its pre-pandemic level, the debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to increase through 2024‑26. Thus, we still feel the current sovereign spread is too low.

Spain: Services Spur On Divergence Still

Still very much at the top end of the EZ growth ladder is Spain; it is notable that while Spain’s economy was slower to recover from the impact of Covid-19 than many of its peers, it is now almost 7% larger than it was by end-2019 while the Eurozone as a whole has expanded by just 4.5% in that period. That gap may increase further, not least after a 3.0% GDP surge in 2024 (0.4 ppt up on our view three months ago) slows to ‘only’ a little changed 1.8% in 2025 and then to 1.5%, all well above our EZ projections. Thus the gap above the EZ average by 2026 rises to some 3.5 ppt but where that 2026 projection is largely in line with estimated current per capita GDP growth. As suggested previously, the EZ more recently has been driven solely by services and it is the fact that Spain’s economy has a much larger share of services in its make-up compared to the EZ average (75% vs 70%) has helped the country to out-perform. More notably, and unlike the EZ as a whole, there is little in survey data to suggest that services strength is ebbing, boosted by a tourist backdrop which has seen a 10% yr/yr rise in international visitors and where this may account for a quarter of the 3% GDP growth rate we now expect for this year (not surprising as tourism accounts for 13% of Spain’s GDP). But this is not the whole story as service exports have led the way and are expected to continue doing so into 2025 as they are not going to be hit by any tariffs and may be led in particular by banking to engineering services so that such exports will largely match the boost from tourism, which may now be fading. This slowing reflects what we think will be a tourist sector where demand may be held back by high prices, over-crowding and the growing resistance from locals (involving protests) regarding apparently excessive overseas visitors.

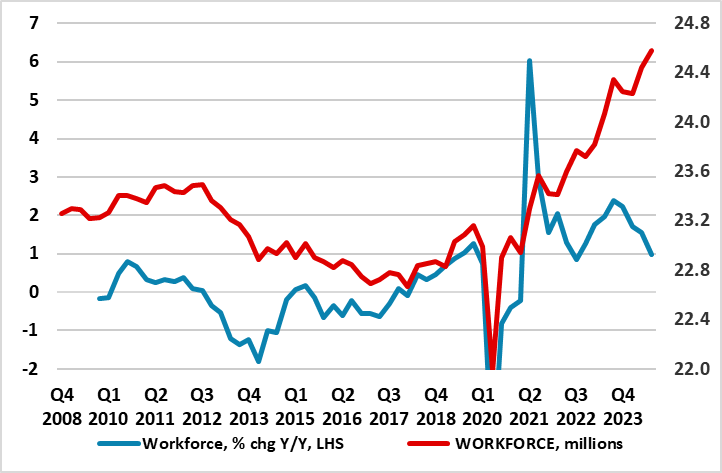

Other sectors are also buttressing growth, with renewable energy now accounting for half of Spain’s electricity usage. There is also the construction sector where current strength is likely to persist given what seems to be a growing imbalance between housing demand and supply. But at the heart of this is a robust labor backdrop which has seen a marked rise in the Spanish workforce (largely a reflection of returning emigration) enough to have effectively increased the economy’s potential growth rate. But that workforce rise has started to reverse and that this may continue (Figure 5). This is the main rationale for the slowing we see in terms of GDP in coming years although a hardly robust capex backdrop (possibly hindered by ever clear political divisions hurting company sentiment) will not be helping.

Even so, the unemployment rate may continue to fall, although its reduction will be moderate from 11.8% in 2024 and to 10.6% in 2026. Regardless, consumer demand is expected to continue lagging overall growth, and where export strength may also ebb - this largely a result of tourism possibly peaking. Thus we see a largely unchanged current account surplus of just over 2% of GDP both this year and through 2025.

Figure 5: Slowing Workforce?

Source: INE

On the inflation side, we expect the underlying trend to be one of more modest moderation. Indeed, we see inflation slowing to an average of 2.8% this year (a slight change) but with the projection of 2.0% for 2025 intact, this also the outlook for 2026 inflation. This reflects some slowing in terms of services inflation, reflecting a limited impact of the so-called second-round effects.

Otherwise, Spanish PM Pedro Sánchez has managed to maintain a minority coalition administration amid ever clearer political divides. Even so, the budget deficit is forecast to decline further in 2025, to 2.6% of GDP, despite somewhat higher interest expenditure driven by positive developments in tax revenue, particularly from direct taxation, boosted by strong nominal GDP growth. In 2026, the general government deficit is projected to slightly increase to 2.7% of GDP as the levies on banks and energy companies are expected to expire. The debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to continue narrowing in gradually in 2025-2026, to around 101%, due to the less favourable interest-growth rate differential.