Eurozone Outlook: At A Crossroads?

· For once in a long while, we have upgraded the EZ activity forecast and for 2026 actually to a notch above consensus thinking. However, the current backdrop still suggests that while the economy has been growing afresh it is doing so timidly, with downside risks persisting more clearly for much of the current year and where some such risks may be materializing.

· All of this reflects the competing forces of planned defense and infrastructure-induced fiscal expansion in the EU against the activity and possible inflation damaging tariff threat by the U.S. This juxtaposition of near terms risks and medium-term hopes has persuaded the ECB to speed up its easing but now we forecast only two more cuts (ie 50 bp) in this cycle to a 2% ECB deposit rate.

· The fiscal expansion may be less sizeable, take longer to exercise and be less broadly spread across the EZ than perhaps the European Commission would have us believe. It may not trigger a fiscal (and perhaps banking sector) crisis but could mean financial conditions remain tighter for longer than otherwise!

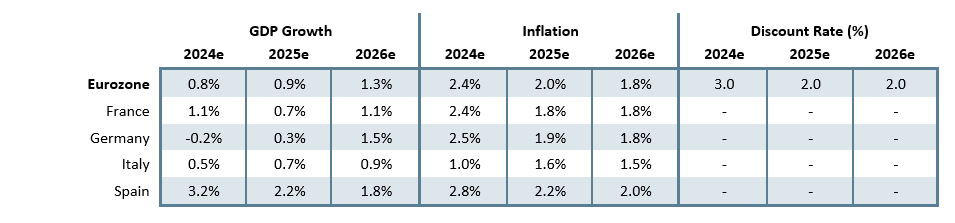

· Forecast changes: Compared to the last outlook, we have actually upgraded the overall EZ growth outlook, with a slightly less-fragile further recovery for 2025 but a ratchet up to trend-type growth in 2026. More notable, then is the hardly-revised and still-soft EZ HICP inflation outlook in which the target is undershot on a sustained basis into 2025 and beyond. As a result of the growth revision, we have reined in our ECB policy rate forecasts to show a little less easing.

Our Forecasts

Source: Continuum Economics, Eurostat

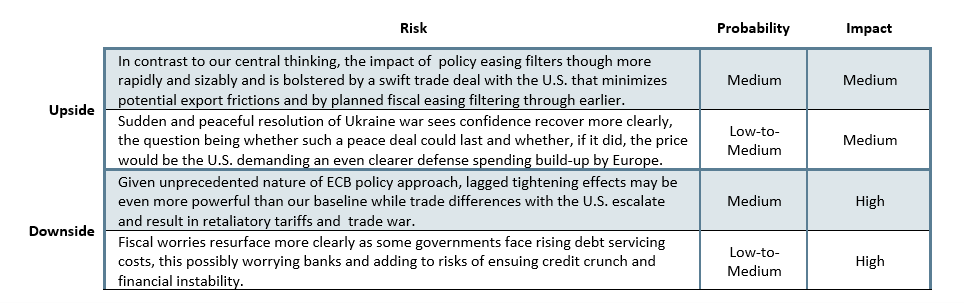

Risks to Our Views

Source: Continuum Economics

Eurozone: Near-Term Downside Risks, Medium-Term Upside Hopes

Europe, whether it be the EU and/or the EZ, is at a crossroads, politically, economically and fiscally. It has to show support to the Ukraine, wary that failing to do so could only encourage Russia to attack another Eastern European country at a later date. In tandem, it needs to build military strength in case the Trump administration decides to weaken NATO’s Article 5 support even for a major European country like Poland or Germany (here) – the Trump administration is unlikely to join a war with Russia in the scenario of a Baltic state being attacked. European security need to change materially. At the same time, it has to face up to what will be clearly economy-damaging tariffs that the U.S. is threatening, both by trying to bolster economic activity otherwise but also trying to placate US trade wrath by promising to increase imports - in the short-term to address its shifting defense needs. It has already set the defense process in motion with what the European Commission suggest is a EUR 800 bln package of possible fiscal space that could be mobilized, EUR 650 bln of which based around member states would increasing respective defense spending by 1.5% of GDP on average. However, this so-called ReArm package is very much an aspiration, with even the Commission implicitly accepting that not all EU countries would have the fiscal leeway to do so.

But it does seem clear that Germany has turned an economic and fiscal corner (see below) to a degree that should boost its growth clearly from 2026 onwards and this will have direct and indirect consequences for the EZ economy. With this in mind, we have lifted the EZ 2026 GDP outlook by 0.2 ppt to 1.3% - the 0.1 ppt upgrade for this year is more to do with better base effects after recent revisions to 2024 growth numbers. And the outlook after 2026 looks somewhat brighter too. But there are still a host of imponderables, some to do with the timing of likely fiscal and defense initiatives; some to do with to what degree they may boost EZ growth only modestly due to the likely large import content to begin with and also the extent to which they may be tempered by what may be more sustained tightening in financial conditions due to interest and exchange rates being higher than otherwise would be the case. There is also increased uncertainty emanating very much from political divides and policy paralysis in several countries (clearly France) and where, as suggested above, greater fiscal consolidation measures from several countries that will continue beyond next year this even if EU-wide fiscal rules are loosened as even Germany is now calling for.

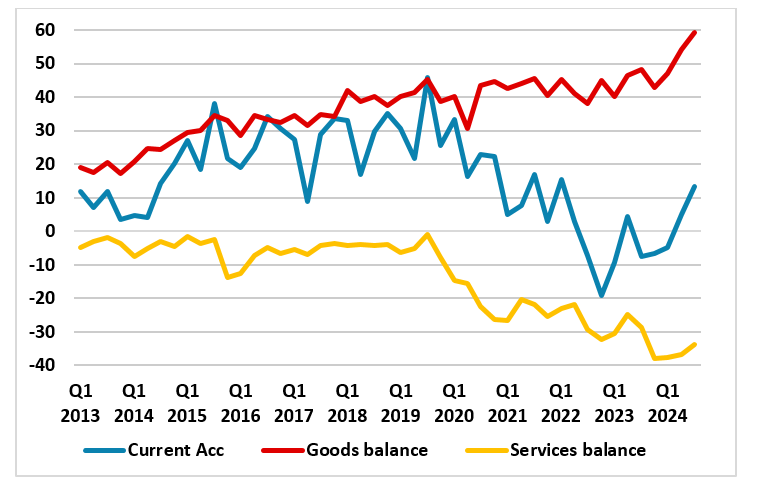

Even so, this puts our new central view a little above consensus thinking– a first for us – at least in the recent past, but this could change (possibly in either direction) once some details regarding U.S. tariffs start to clarify from next month. As for the impact, this is obviously hard to judge but work has been done to model some likely effects such as that recently by the London School of Economics. This very concludes that a 10% tariff would hit GDP in the European Union by modest reduction of 0.1%. Within Europe, the impacts would vary significantly: Germany could see a 0.2% drop in GDP, while in Italy the decrease could be negligible and hardly much worse for France. But importantly, the research suggests that retaliatory measures by China and/or the EU would likely worsen economic outcomes for all parties involved, potentially sparking a damaging trade war, this risk even clearer if the EU’s ultimate retaliation stretched out a possible digital services tax – NB it is notable that the EU’s sizeable surplus with the US is much more balanced once services are included (Figure 1). But the EU will offer carrots as well as sticks, and has already suggested buying more US energy, military and agricultural goods as a concession, even though the latter may be somewhat contentious.

In terms of our forecast the impact could be much more sizeable. US tariffs on steel and aluminium of 25% will hit already recession-bound EZ manufacturers, which export some EUR 3bn of steel and some EUR 2bn of aluminium, thus affecting approximately 1% of total goods exports with the US. But the damage could be much larger given the threat of tariffs based around so-called trade reciprocity. At this juncture we consider the downside from actual tariffs as much as a sizeable risk than a quantifiable reality, but (as suggested above) cannot ignore the likely sustained impact of uncertainty weighing on activity into 2026.

Figure 1: Broad Relative Balance Trade with U.S.?

Source: ECB, EUR bln – bilateral trade EZ- U.S.

Fiscally, having tightened significantly in 2024 on account of the withdrawal of a large part of the energy and inflation support measures, we no longer see the fiscal stance continuing to tighten into 2026, the question being the extent of any rebound from the circa 3% of GDP the budget deficit may reach this year. Thus, with an EZ headline budget gap that may rise into 2026, the fall in the EZ government debt ratio to 88.5% of GDP last year will likely soon be followed by a rise. This is especially given that the EU Commissions fiscal plan would mean the EZ primary deficit rising from around 1% of GDP this year towards 3% raising question about fiscal sustainability afresh.

All of which comes against a current economic backdrop suggesting that the EZ economy is facing clear downside risks which may now be materializing. The fact that growth rates among the EZ main economies have diverged even further of late (Spain robust, Germany possibly contracting afresh) actually reflects a marked disparity in growth rates between hitherto strong services and persisting declines in goods output, this evident in both survey data as well as official national account data. But recent survey and now official output data are increasingly suggesting weaker activity, now increasingly embracing weaker services to a degree that imply that the support the sector has given the whole EZ economy in the last year or so may have dissipated, if not reversed. Indeed, GDP growth could even be negative this quarter, especially given the very weak manner 2024 ended.

As for the trade balance, the anticipated cyclical, and possibly structural, recovery in imports into 2025 as well as what may be a weak global economy weighing on exports will also mean that the improvement in the current account surplus last year (at over 2.5% of GDP) may reverse into 2026. This is also a headwind to GDP growth.

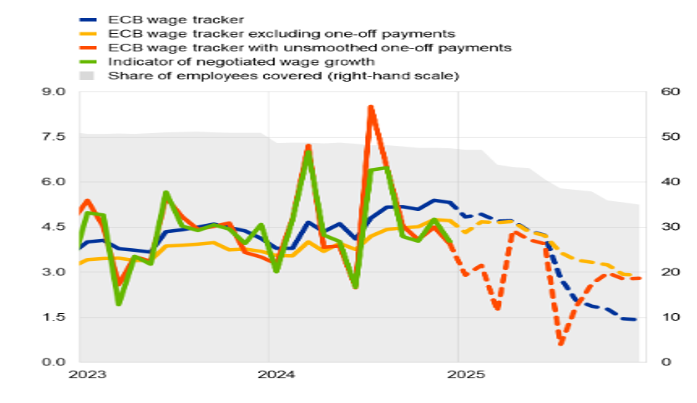

Amid what has been a disinflation process so far very much supply driven, but encompassing what has already been a marked softening of underlying inflation, we still envisage headline HICP moving below 2% more durably later this year with the core not far behind and then remaining below through 2026. This picture is little changed compared to the previous Outlook, but encompasses evidence of softer cost pressures, especially in regard to wages (Figure 2). Indeed, the omens point to services inflation slowing in due course, something we think will emerge more visibly into 2025 as wage growth slows to pace consistent with the inflation remit.

Figure 2: ECB Numbers Suggest Wage Pressures Moderation Clearly?

Source: ECB

ECB: Ready to Slow Down?

Having cut rates at successive meetings dating back to last September, the ECB may now slow remaining easing. This not only reflects that policy is now decidedly less restrictive with a discount rate at the current 2.5%, but it may wish to assess the impact of moves to date, something that the hawks on the Council may start to highlight. But perhaps the main factor is that even with the projections it updated this month consistent with rates falling to 2% (broadly what the ECB has hinted is neutral), it will wish to get clearer details of the additional positive and negatives now coming to light. The former obviously being the increasingly flagged fiscal expansion and the latter the size and breath of tariffs. We think that the risk posed by tariffs suggests more easing in the short-term with 25 bp moves probably at the June and September meetings, albeit an April 17 move not ruled out especially if the bank lending survey due two days before that Council meeting show further signs of credit standards tightening. But by Q3, the ECB may have a clearer handle on the economic outlook, and with it likely that its current 1.3% 2027 GDP projection may be upgraded, the Council may think it can then stop. However, this will at least initially be framed as a pause and certainly with no hints of any policy reversal as fresh HICP projections are still likely to show broadly on-target inflation.

But for next few months the dominant ECB issue will remain whether downside growth risks have turned into reality with it clear that growth worries have risen. Indeed, continued downside risks have other aspects, equally worrying, especially as (even according to its own recent Financial Stability Review). And should these downside risks persist it is possible that amid a continued sub-par growth outlook into 2026, then further easing may be on the cards into 2026. It is also possible that amid rising EZ bond yields, but largely generated by German fiscal expansion, the ECB may rein in its QT program.

Germany: Headwinds Changing Direction?

Almost out of the blue, it does seem as if Germany and its economy are undergoing a sea-change, one that looked highly unlikely before what was an election result last month that hardly pointed to any fresh electoral policy mandate.

Indeed, an agreement by Germany’s likely next coalition partners and the Greens has amended the so-called debt brake and thus provides the economy with both fresh fiscal scope and new economic aspirations. It thus points to an end (or at least a diminishing) to the budgetary shackles that surely have not only contributed to weak growth in Germany (and probably much of Europe) in recent years but also that has probably been curtailing the economy’s potential.

What are effective changes to the constitution would seemingly have three effective prongs. Perhaps most high-profile is that defense spending above 1% of GDP would be exempt from any debt brake – effectively removing a ceiling on borrowing so that Germany could more easily increase such expenditure from the current 2% of GDP to an aspiration of 3%-plus. But in terms of size, it is the planned deficit-financed infrastructure fund worth EUR 500bn (ie around 11% of GDP) that may be the most ground breaking even though it is to be spread over a ten-year period. But there are also now plans to allow the federal states (Laender) to run small deficits rather than being compelled to balance their budgets.

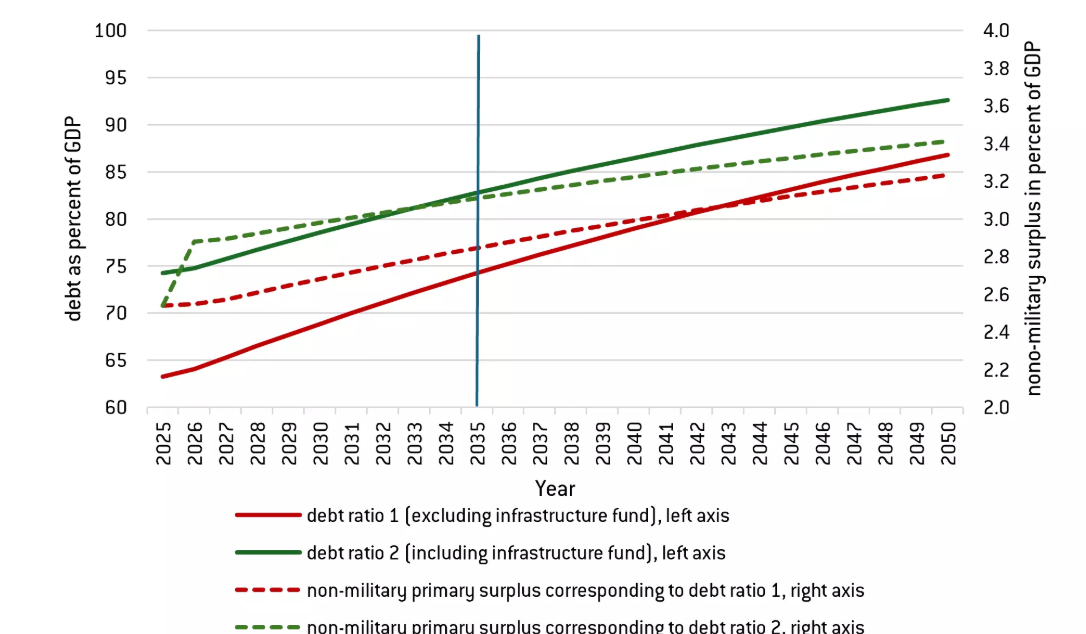

The bottom line is that a German budget gap that looked to be around 2% of GDP could turn into one of well over 4% probably not this year but into and beyond 2026 (Figure 3). As a result, the government debt ratio would rise from its current 63% of GDP to above 80% over the next decade possibly without negative repercussions – not least as Germany has already suggested EU-wide fiscal rules (which this initiative compromises) need to be relaxed. While the increase in defense spending has attracted most attention given its international perspective, perhaps any plan to upgrade Germany’s fragile and aging infrastructure is the most important, especially as unlike the defense initiative it will (by definition) be spent domestically. But some of this will boost imports as will defense spending even with an aspiration of being directed towards domestic/European producers. As a result, it looks very likely that the circa-6% of GDP current account surplus likely this year will be reduced – both helping growth elsewhere and politically speaking addressing the source of what may be growing trade tensions and trade wars.

We see German GDP picking up to 1.5% next year (0.5 ppt more than envisaged in the last Outlook) after a lame and little revised 0.3% this year, but with a further and possibly larger pick-up beyond 2026, but there are many imponderables. This reflects several factors, the most notable being that it will take time for the additional spending on both defense and infrastructure to take effect and that there is little spare capacity, certainly in the German labor market – the exception may be the recession-bound construction sector. Moreover, defense spending does not boost GDP on a one-to-one basis (ie a fiscal multiplier of less that one), and only partly due to the likelihood that much of the equipment spending will be imported. In addition, both through what may be a shift higher in the euro and in terms of interest rates (higher yields and possible deferred ECB easing) financial conditions may be tighter than otherwise. Finally, it is widely considered that not only frail infrastructure has been holding back the German economy but(over) regulation and bureaucracy have been even more restrictive. The question is the extent to which this can and will change, especially as support for the likely CDU led new coalition may have to be at least partly bought with more social spending too. As for inflation we have not altered our projections and await more details instead, this partly a result that these fiscal moves may boost Germany’s lame potential growth rate.

Figure 3: Scenarios for German Government Debt Build

Source: Bruegel

France: A Political Crisis Bubbling on the Back Burner

The planned German fiscal expansion was very good news for France and not just because of the boost to EZ-wide activity it and the EU defense initiative will bring. As important was Germany’s call for EU-wide fiscal rules to be relaxed, this all the more important given the large budget deficit that France is facing. In this regard, we have made little change to the French economic outlook for this year or next, still seeing GDP growth of 0.7% and then 1.1% respectively as fiscal restraint continues to be the underlying theme. Indeed, whereas President Macron has been perhaps the most vocal about what the EU must do to counteract any Russia threat, we do not see France being a major part of any clear defense-based fiscal expansion given its adverse budgetary backdrop and outlook. Indeed, the European Commission has made clear that countries should consider ramped up defense spending – ‘if they have the fiscal space’. And even with what may soon be watered down EU fiscal rules a French budget gap that may be close to 5% of GDP even beyond next year risks seeing the debt ratio (likely to rise to 115% of GDP this year) rise even further. In addition, the political situation hardly bodes well for the fiscal picture. Admittedly, last month did see the minority administration force through a budget bill, thereby avoiding the fall of the government and ensuing accentuating political uncertainty. But the cost was that planned fiscal consolidation has been scaled back so that the 5% of GDP aspiration has now turned into a planned gap of 5.4% this year and we see upside risks, not least given the concessions required to secure political support for the budget amid both parliamentary fragmentation and an absence of broad-based popular support. Indeed, we still see the risk that the fragile government may be toppled after July when fresh parliamentary elections can be called. Moreover, this could result in adjustments to the recent pension reform – potentially critical as pension spending is among the highest in the EU at over 14% of GDP, ie some three ppt above the EU average

With this in mind we reiterate that France does not (yet) face a fiscal crisis but still faces a tighter fiscal stance into 2026 and beyond. Admittedly, given France’s large defense industry (providing almost 10% of global arms exports), it should be beneficiary of added EU spending – hence its demands that the EUR 150 bln proposed loans from the EU be not be frittered by buying from outside the EU.

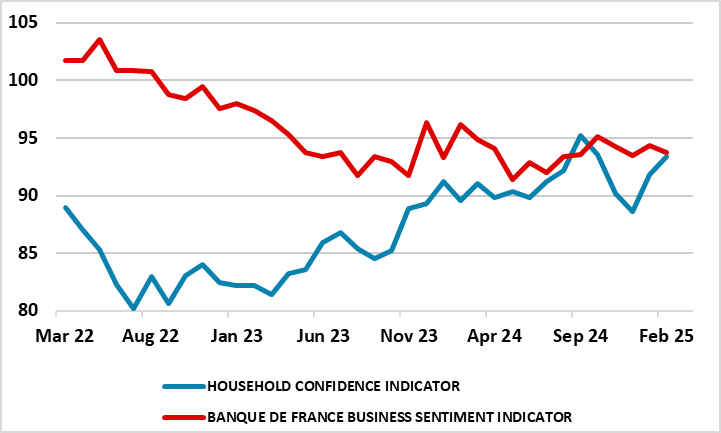

Regardless, the 2025 GDP picture is partly distorted by weakness from late-2024. But private consumption will be weak as energy support measures are fully reversed into 2025 and as high savings remain locked up in illiquid assets. Investment is projected to recover progressively into 2026 but only after possible fresh drops in coming quarters as uncertainty dominates. Both of these themes highlighted by respective weak consumer and business confidence (Figure 4). Meanwhile, over the forecast horizon, net exports are set to have a minimal contribution to growth, the question being whether imports again act to bolster GDP through 2025. One (relative) positive is that France is relatively insulated from any U.S. trade flare-up, and could actually be a beneficiary if even heftier tariffs are levied on China.

However, this soft growth outlook will reinforce the broad disinflation already very much evident. Thus we still envisage CPI inflation at 1.8% this year and likely to stay under 2% through 2026, albeit with risks on the upside from possible fiscal measures. This inflation picture will not help the fiscal side and reflects a continued reining in pricing power and a rise in the unemployment rate back above 7.5% through 2025 and perhaps 2026 and where companies are likely to see profit margins fall further!

Figure 4: France – Both Consumers and Companies Still Gloomy

Source: INSEE, Bank of France – 100=neutral

Italy: Playing its Trump Card?

As we underlined three months ago, Italy is unlikely to be major victim of any U.S. trade restrictions in the coming two years, save for some damage to its transport sector. Indeed, it could even benefit on competitiveness grounds should China still higher tariffs than the extra 20% already implemented. But the outlook is still sobering even though we have upgraded the 2025 GDP outlook by a notch to 0.7% and that for 2026 (by a 0.2 ppt) to a not-much better 0.9%, projections that very much square with current business survey data and also bank lending showing still negative growth in the private sector. Admittedly, this year’s projection would be up on the miserly 0.5% of last year but this is largely base effects as crucial in this outlook is the consumer, where spending last year may even have sunk slightly, partly due to restrictive financial conditions but mainly to the wind-down of the Superbonus building tax credit (a generous tax incentive for housing renovation). This should be entirely phased out by year-end. But amid what has been a still-falling jobless rate (despite record-high labor force participation) and actual real wage growth (nominal gains of up to 4% are seen again in 2025), the consumer should bounce back – something like 1% gains are possible in both the coming two years, even given CPI inflation picking up slightly to 1.6% this year and something similar into 2026. The question is whether this recovery will fuel a pick-up in imports. Admittedly, exports may also recover into 2026, but nothing major is anticipated given the weakness in key neighbouring economies, most notably Germany. As a result, we see the current account surplus staying just over 1% of GDP in the coming two years but with upside risks at time goes by as Italy’s large arms exports (5% of the global market) benefits from rising EU defense spending.

We still consider that the main downside risk is that the wind-down of the Superbonus triggers a larger and more persistent contraction in housing investment, the latter having been a key source of growth over 2021-23. But on the upside, the acceleration in public investment related to the National Recovery and Resilience Plan could boost growth in 2025-26 more than expected, not least as a full utilization of New Generation EU funds implies that such-related spending needs to be ramped up from about 1% of GDP in 2024 to about 2.5% of GDP on average over 2025-26.

As was the case three months ago, fiscal worries seem contained, although the any fall in sovereign spreads vs Germany at a 10-year horizon compared to the last Outlook is more a German story than matters Italian and still implies higher actual yields of late. Partly this reflects genuine fiscal improvements, albeit largely a one-off result of the unwind the Superbonus scheme. However, the primary balance moved into a small surplus even last year and may turn more positive in 2025 (around 0.5% if GDP). But while this may still see budget deficits of around 4% of GDP persisting this year and possibly next (as still envisaged three months ago), upside risks persist not least given a structural gap of over 4%. Indeed, the European Commission warn that even into 2026, a continued rise in interest expenditure to 4% of GDP will mean that after, the debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to increase through 2025‑26. Thus, we still feel the current sovereign spread is too low but not significantly so.

Spain: Divergence Persists

While dispensed with decades ago, Spain’s fascist past still reverberates among much of the population with an aversion to the military – this largely explains why the country is at the bottom of the NATO ladder in spending just 1.3% of GDP on defense. This aversion is clearest among left leaning parties, including the current minority Socialist administration, but it has succumbed to EU pressure to lift such spending to 2% - but only by 2029. More such pressure will surely come but Spain certainly does not need any defense-induced fiscal medicine given its more than solid economic performance. In addition, it still has its own fiscal problems with structural budget gap of around 3% of GDP last year widely seen persisting into 2026, all keeping the debt ratio at just over 101% of GDP. NB: The EU has accepted a government seven-year adjustment plan including the Next Generation grants and investments (without reforms, the required adjustment would have to take place in four years). And furthermore, it is not too vulnerable to likely US tariffs with less that 1% of GDP stemming from exports to the U.S., less than half the EZ average.

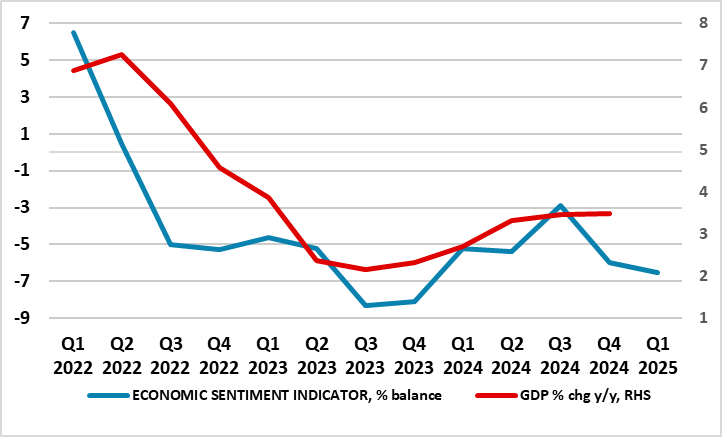

All of which persuades up to upgrade the GDP picture – again – but where surveys do suggest some slowing is now underway (Figure 5). Still very much at the top end of the EZ growth ladder it is notable that while Spain’s economy was slower to recover from the impact of Covid-19 than many of its peers, it is now 7% larger than it was by end-2019 while the Eurozone as a whole has expanded by just 4.5% in that period. That gap may increase further, not least after a 3.2% GDP surge in 2024 slows to ‘only’ a 2.2% in 2025 and then to 1.5% in 2026, all well above our EZ projections both around 0.3-0.4 ppt up on our view three months ago. Thus, the gap above the EZ average by 2026 rises to some 3.5 ppt but where that 2026 projection is largely in line with estimated current per capita GDP growth. As suggested previously, the EZ more recently has been driven solely by services and it is the fact that Spain’s economy has a much larger share of services in its make-up compared to the EZ average (75% vs 70%) has helped the country to out-perform. More notably, and unlike the EZ as a whole, there is little in survey data to suggest that services strength is ebbing, boosted by a tourist backdrop which has seen a 6% y/y rise in international visitors and where this may again account for a quarter of growth we now expect for this year (not surprising as tourism accounts for 13% of Spain’s GDP). But this is not the whole story as service exports have led the way and are expected to continue doing so into 2025 as they are not going to be hit by any tariffs and may be led in particular by banking to engineering services so that such exports will largely match the boost from tourism, which may now be fading, held back by high prices, over-crowding and the growing resistance from locals (involving protests) regarding apparently excessive overseas visitors.

But at the heart of this is a robust labor backdrop which has seen a marked rise in the Spanish workforce (largely a reflection of returning emigration) enough to have effectively increased the economy’s potential growth rate. But that workforce rise has started to reverse and that this may continue. This is the main rationale for the slowing we see in terms of GDP growth in coming years although a hardly robust capex backdrop (possibly hindered by ever clear political divisions hurting company sentiment) will not be helping.

Even so, the unemployment rate may continue to fall, although its reduction will be moderate from 11.4% in 2024 and toward 10.5% in 2026. Regardless, consumer demand is expected to continue lagging overall growth, and where export strength may also ebb - this largely a result of tourism possibly peaking. Thus we see a largely unchanged current account surplus of just over 2.5% of GDP both this year and through 2026.

Figure 5: Surveys Suggest Some Slowing Underway?

Source: INE, European Commission

On the inflation side, we expect the underlying trend to be one of more modest moderation. Indeed, we see inflation slowing to an average of 2.2% this year (a slight upgrade due to swings in energy taxes) but with the projection of 2.0% for 2026 intact. This reflects some slowing in terms of services inflation, reflecting a limited impact of the so-called second-round effects.