ECB April Account: Neutral Rate Not Necessarily a Terminal Rate

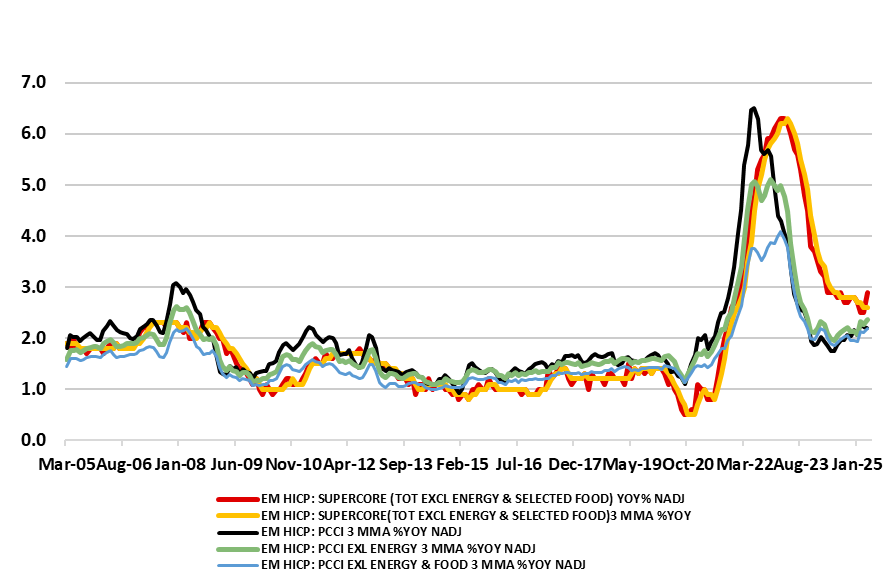

The account of the April 16-17 ECB Council meeting suggested that the policy decision was more of a clearly agreed consensus, this papering over continued divides regarding the outlook; the risks from tariffs; and where inflation risks lie. The seventh and widely expected 25 bp deposit rate cut (with some suggesting a larger move may have been better) was overshadowed by the ECB’s communication shift about the outlook thereafter, no longer talking about how restrictive policy may be. But it was clear that even though a June moves was clearly expected, differences over the extent and direction if inflation risks remained. Notably, the hawks specifically, and the Council more generally, accepted that that upside price risks had not vanished with some note made of the rising momentum that had been detected in the PCCI indicators warranted monitoring. In this regard the fact that the PCCI and super core underlying measures have since risen further (Figure 1) may perturb some of the Council, and especially so if forthcoming May HICP data do not confirm that the April services surge was purely a statistical and calendar anomaly.

Figure 1: ECB's Favoured Underlying Inflation Gauges Starting to Edge Higher?

Source: ECB - Persistent and Common Component of Inflation (PCCI)

Rhetoric Rationale

Perhaps the key aspect in the account was the rationale behind a shift in communication as members noted that it was time to remove the phrase “our monetary policy is becoming meaningfully less restrictive” from the monetary policy statement. We argued at the time that this was entirely appropriate not least given the manner in which financial conditions has been tightening; the fall in official rates had been giving misleading signals about policy restriction. Instead as the ECB grapples with increasing downside risks (to both growth and inflation) that requires risk management to drive policy ahead and which we feel is consistent with ECB following what it has termed an agile, data-dependent and meeting-by-meeting approach to determine policy.

However, the discussion was more nuanced, with it agreed that reference to a restrictive policy stance, so that monetary policy was contributing to disinflation, was no longer needed. In particular, dropping the sentence avoided the perception that reaching a neutral level of interest rates was the end point of the current cycle, which was not necessarily the case. Moreover, dropping the sentence did not imply that monetary policy had necessarily left restrictive territory. At the current juncture, there was no need to take a stand on whether monetary policy was still restrictive, already neutral or even moving into accommodative territory. Such a categorisation, especially in the current turbulent context, was very hard to provide. Instead, the change in wording was seen as consistent with an approach that was not guided by interest rate benchmarks but by the need to always determine the policy stance that was appropriate, this more chiming with our understanding of the rhetoric shift. In other words, policy would be set so as to provide the strongest assurance that inflation would be anchored sustainably at the medium-term target, given the set of initial conditions and the shocks that the Governing Council had to tackle at any given time.

Admittedly, given that tariff clarity may still be muddied by the time of the June ECB meeting, there is possibility (but may be not a probability) of a pause at that juncture, this risk possibly accentuated by the tariff increase pause and by inflation. We would underscore that disinflation provides the ECB with the scope to ease policy while weak activity (actual and/or threatened) provides the rationale. Thus any further worrying inflation outcomes could complicate the policy outlook or at least cause delays in easing. With this in mind, the April ECB meeting accepted that upside price risks had not vanished with some note made of the rising momentum that had been detected in the PCCI indicators warranted monitoring. In this regard the fact that the PCCI and super core underlying have since risen further (Figure 1) may perturb some of the Council, and especially so if forthcoming May HICP data dot confirm that the April services surge was purely a statistical and calendar anomaly – we think that the late Easter was the cause!

But as for our outlook, the increase in downside growth risk the ECB now recognises stem not just from the direct consequences to trade from the U.S. imposed tariffs but also from export diversions and the increasing threats of inter-twined slumping business confidence and capex intentions as well as the surging euro damaging competitiveness, the latter accentuating already tighter financial conditions. All of which suggest to us that the damage that tariffs may accentuate will trigger 2-3 more 25 bp cuts after and where ECB may even admit it may have to revisit the QT outlook.