UK Productivity: Starting to Recover - Maybe?

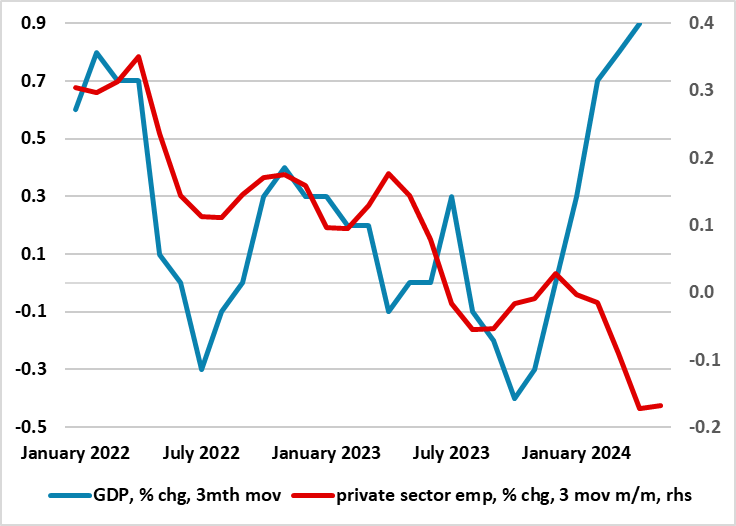

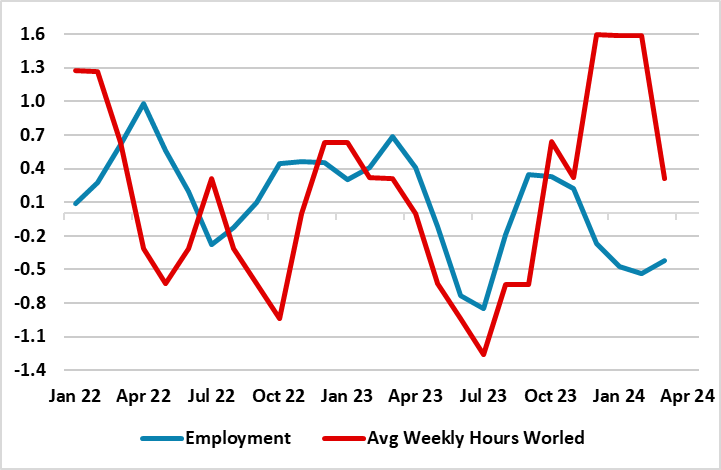

Amid the new government’s economic priority to boost the trend or potential growth rate, any hint that this could be occurring would be welcome and important. With this in mind, it is notable that after the mild recession in H2 last year, the ‘recovery’ through this year is much clearer than any expected with GDP growth notably positive, and with less apparent volatility. Potential growth has two components, swings in the workforce and swings in productivity. In this regard, there are hints that this recent GDP recovery may be productivity driven given that it is coming alongside ever clearer falls in employment (Figure 1). However, we are sceptical, instead thinking that the jobs weakness questions the validity and durability of the apparently solid GDP rebound, which we suggest has been driven by a recovery in average hours worked that may now be petering out (Figure 2). This notion is backed up by survey data that have taken a turn for the worse of late. Regardless, the data thus needs watching. But even if productivity is picking up, this is already assumed in the fiscal projections and thus will not provide improved budgetary leeway for new Chancellor Reeve.

Figure 1: : Clearer GDP Recovery But Contrasts with Labor Market?

Source: ONS, CE

Productivity is basically the change in output in any given period divided by the effective change in the amount of work, the latter made up by swings in employment and changes in the amount of hours worked of those in employment. Output as proxied by GDP growth is now likely to average near 1% this year, twice what we thought a few months ago after the repeated upside surprises in real monthly activity data. Indeed, coming in more than expected, GDP rose by 0.4% m/m in May accentuating the bounce in the two months prior to the flat April reading. As a result, this would be consistent with a circa-0.6% Q2 q/q outcome, building and almost matching the strong but possibly misleading Q1 jump.

Better GDP backdrop Has Little Fiscal Benefit

But this will not have any major fiscal benefits. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) already has a well above consensus estimate for growth this year of 0.8%. Shifts in the OBR’s productivity estimates — a key driver of trend growth — are enormously consequential. A 0.5 percentage point upward or downward shift in the OBR’s productivity growth forecasts can add or subtract upwards of £40bn in borrowing, the office says. And even if the GDP bounce persists there would also be little fiscal benefit as the OBR is already assuming very optimistically average GDP growth of close to 2% per annum in the next three years, this based on what we think are equally optimistic assumptions about UK productivity (ie average above 1% over this outlook period. It is also unlikely to affect monetary policy as the BoE’s inflation forecasts are based around almost as optimistic productivity assumption, although the MPC would have to make major changes to its 2024 projections with some possible inflation repercussions. Indeed, many would regard a stronger GDP growth profile as being (at least on the margin) more inflationary. But this would be a misnomer as the inflationary consequences of any pick-up in growth depends on whether it is demand or supply driven. If productivity is recovering then it means more supply and this would be disinflationary and could mean that that the BoE may have to assume an even greater degree of spare capacity in the economy that already evident in its projections.

Figure 2: Employment Weakness Countered by Recent Hours Worked Surge?

Source: ONS, CE, % chg m/m, 3-mth avg

But such a reassessment would be premature we think. For a start, the GDP pick-up maybe real, partly based on increased business confidence that has been framed by the expectation and delivering of a more stable political environment in the UK. But rather than this having been driven by a pick-up in productivity, it is merely the fact that the weakness in employment has been offset by an increase in average hours worked and this now seems to have run its course. Moreover, the apparent resilience, if not strength, in the GDP data not only contrasts increasingly with employment weakness but also survey data. It is also a question of the extent to which GDP has been driven of late public sector gains and by import weakness as was the case in Q1.