Brazil: Wage Inflation Will Likely Not Be a Big Deal

Our analysis delves into recent trends in the Brazilian labor market, focusing on CPI and wage inflation. Utilizing a model akin to Ghomi et al. (2024) and Blanchard and Bernanke (2023), we dissect recent spikes in wage inflation and CPI growth. Notably, our findings suggest that recent wage spikes are more attributable to inflationary surprises than labor market tightness, indicating a backward-looking wage inflation pattern. Moreover, external shocks, particularly in food and energy prices, predominantly drive recent inflation, with labor market developments exerting minimal impact on overall CPI growth.

We model the recent developments on the Brazilian labour market related to the CPI and wage inflation. The model allows us to decompose the recent spike on wage inflation and CPI growth into its main components.

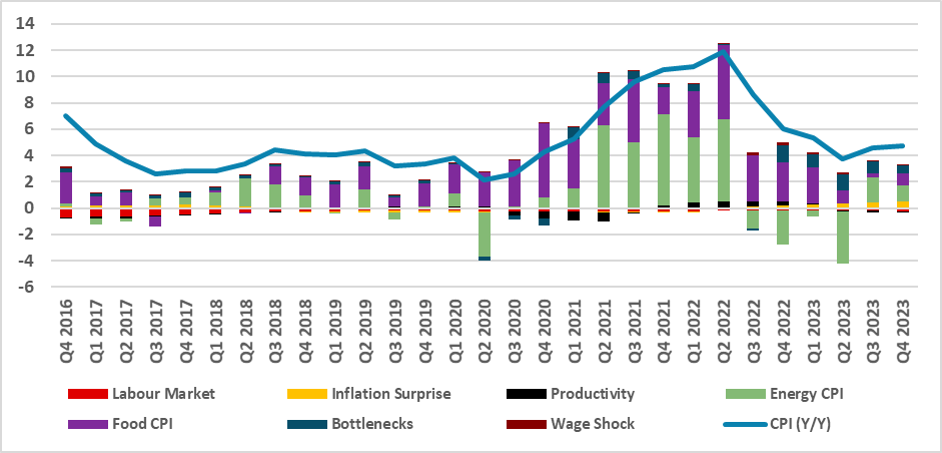

We use the same model as described by Ghomi et all (2024) and Blanchard and Bernanke (2023). The models basically decompose Wage Inflations and CPI Inflation in its main components. With the results of the models we can decompose the contributions of each of the variables into Wage Inflation and CPI Inflation.The four equations of the model are:

In which w_t refers to the annual nominal wage growth, π_t refers to the annual CPI growth, vu is the vacancy to unemployment rate. Note that Brazil does not have a standardized statistic for this variable. Therefore, we construct it as the share of formal job creation to the unemployed population. P is the is the annual productivity growth, calculated as the valued added per employed person, sur is the inflationary surprise variable, calculated as the difference between actual CPI and the expected CPI 12 months before; π^f refers to the annual growth of food CPI, and the π^e is the annual growth of energy CPI. short refers to the bottlenecks seen between supply and demand and we calculate it using the searches in Google trends for “shortage” in Brazil. π_t^e1 and π_t^e5 are the expectations for the CPI one year ahead and five years ahead, respectively. ε is a white noise shock to each equation. We estimate each coefficient by Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) with data spanning from the first quarter of 2006 and the last quarter of 2023.

Once we put the model on the state-space form we can decompose the Wage Inflation and the CPI Growth as the contribution between the exogenous variables and the shocks of the endogenous variables.

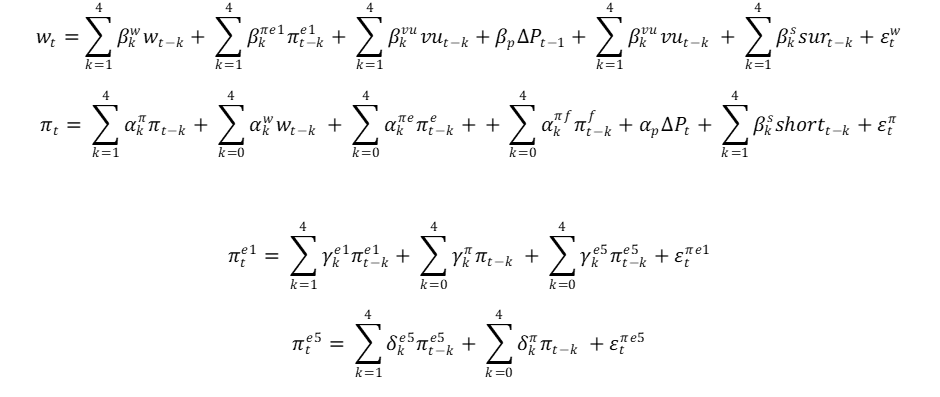

Although the BCB has shown some concerns over the recent development of the labor market in Brazil, indicating some sort of tightness, they also stated that there would be no automatic mechanism between the tightness and the rise of wage inflation. In Figure 1, our vacancy-to-unemployment rate points out that the Brazilian labor market is as tight as ever, with formal job creation outpacing unemployment at an all-time high. However, we need to be cautious with this data as it has undergone recent updates in its methodology, especially concerning formal job creation, which could be creating some misleading results regarding the tightness of the labor market. Still, at an 8.3% unemployment rate, it indicates that there is still plenty of room for the unemployment rate to fall without generating pressures on wages.

Figure 1: Vacancy to Unemployed and Unemployment Rate (Seasonally Adjusted)

Source: IBGE and Continuum Economics

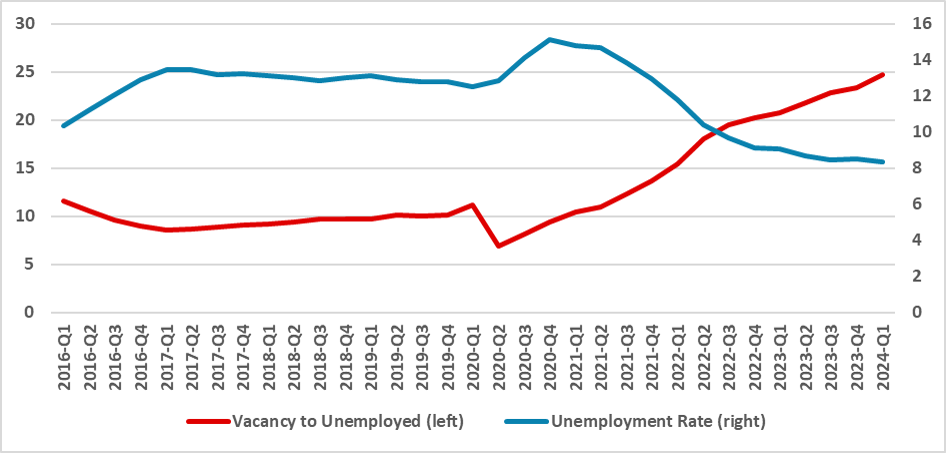

Our model indicates that the recent wage spikes were more related to inflationary surprises rather than to the tightness of the labor market. This means that wage inflation is more backward-looking, indicating that wages respond more to losses in purchasing power, and their expected loss, rather than to supply/demand in the labor market. Once inflation converges, one would expect that wage inflation will tend to stabilize close to the inflation target.

Figure 2: Contributions to Wage Inflation

Source: Continuum Economics

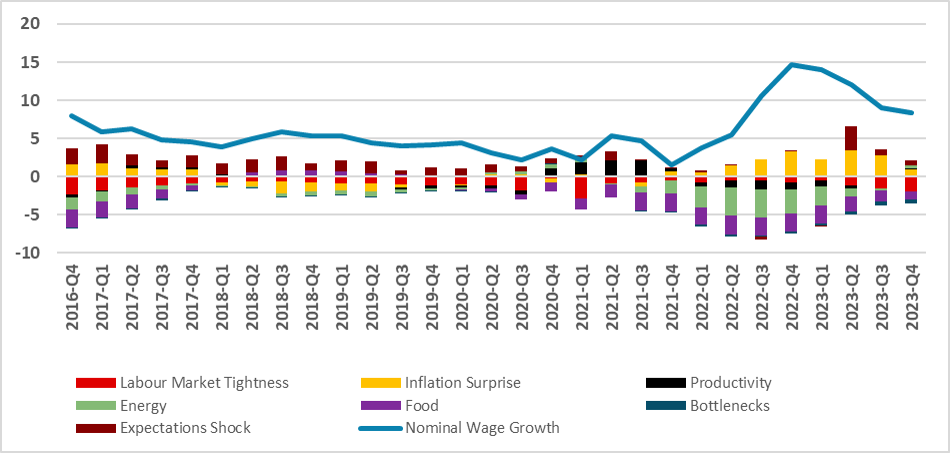

The results of the model also point that the most of the recent inflationary surge were dominated by the shocks seen on food and energy prices, which are rather exogenous of our model. Most of the origins of the surge of food and oil shocks could be related more to a external shock. A similar result is also find for Spain and U.S. using this models. The bottlenecks shocks between supply and demand likely added one to two percentage points on inflation at the end of 2022 when the economy was quickly transitioning out of the pandemic. Overall, wage inflation has low contribution to the CPI, which indicates that the developments on the labour market have a low impact on the general CPI growth. Looking forward, we believe the labour market tightness will have little impact on the CPI, which should become clearer for the BCB in the next months.

Figure 3: Contributions to CPI Growth

Source: Continuum Economics