UK Budget Preview: Demographics to Boost Fiscal Headroom?

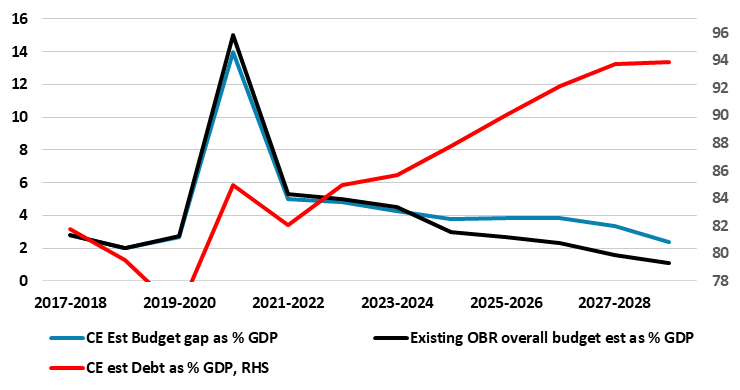

It will be no surprise that with a general election looming almost certainly later this year or so and with the government so far behind in the opinion polls, Chancellor Hunt’s Budget on Mar 6 will be yet another very politically driven affair. It should see gloomier GDP projections but with some tax rate cuts funded that have been highly-advertised. But the question is whether the implied and contentious government spending restraint and still high tax-take are consistent with the debt ratio eventually falling, at least at the end of the rolling five-year forecast period. We think this is unlikely (Figure 1) but the OBR forecast may suggest the opposite, but this may still be a concern for markets, especially if the OBR are openly critical of the fiscal assumptions the government is offering, most notably on the ability to freeze real spending.

Figure 1: Government Debt Continues to Rise?

Source: OBR, ONS, Continuum Economics

There are possible avenues through which the fiscal outlook, particularly the debt scenario could be made, or at least appear to be made, somewhat more credible. The fiscal rue about what debt to include could be tweaked, although this would be controversial. More likely, recent upgraded population projections made by the ONS could deliver a revenue boost that could more credibly fund tax cuts, especially as revenue-lucrative continued personal tax threshold freezes may be masked by cuts in some personal tax rates. Regardless, any tax rate cuts by the Chancellor are aimed at accentuating policy gulfs with Labour, as are the very dubious spending plans.

Still Too Optimistic on Growth

We think that the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) will have to make some downgrade to the economic outlook it offered last November. They need not be dramatic, but the existing real GDP projections for this year and next (0.7% and 1.4% respectively) are well above current consensus thinking and the recently updated BoE projections. In particular, we are also wary about the circa-2% GDP projection after 2025 and especially the recovery in per capita GDP envisaged from this year on (the latter has fallen for seven successive quarters). But other aspects of the OBR projections look more sound, as they already encompass a marked slowing in both wage and consumer price inflation and where an already slowing in the latter is likely to mean an undershoot of borrowing for the current fiscal year. Even so, we see higher large budget deficits than the OBR persisting out to 2029 and with debt rising continuously as a result (Figure 1).

How Much Fiscal Headroom?

As a result, there may be appear to be some added scope for tax cuts over and beyond the £ 13 bn of headroom the OBR identified after November’s Autumn Statement, albeit half of which assumes that fuel duty will be raised in April. This headroom is basically the margin left five years ahead that still allows the level of government debt to have fallen and it is unclear how much it may have changed of late. NB the explicit ‘fiscal mandate’ requires public sector net debt excluding the Bank of England as a percentage of GDP to be falling by the fifth year of the rolling forecast period, which is currently 2028-29. Some of that apparent headroom will have been eroded by recovering gilt yields, which may have reversed a good part of the fall seen into the New Year: the Treasury believes this could have wiped up to £8bn off the headroom figure since the start of the year. But there are also the likely effects of lower than expected inflation, and benefit expenditure in 2028-29 might well be revised down. NB: if the level of nominal GDP at the end of the forecast period in 2028-29 was 1 ppt lower than forecast in November, government receipts would decline by about £14bn.

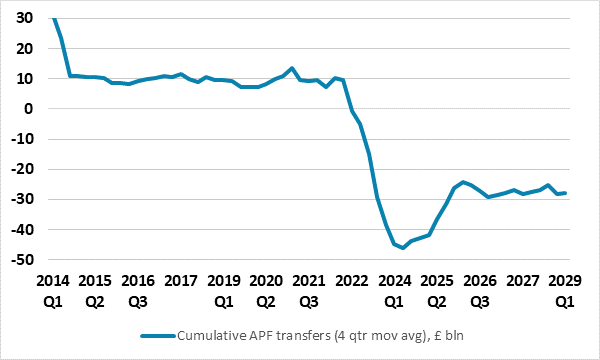

Figure 2: The BoE Giveth and Then Taketh Away!

Source: OBR Forecast of cumulative flows to and from the APF

But the biggest complication is assessing and calculating debt levels is not so much from borrowing but from changes in financial transactions and valuation effects. These have marked but uneven effects on debt driven largely by repayments of Bank of England Term Funding Scheme (TFS) loans. Outside of the TFS, financial transactions add to debt in all years by an average of £ 46 bln, reflecting the losses forecast on the gilts sold by the Asset Purchase Facility (APF) and transactions relating to student loans. It has been suggested that the government could also change its debt rule or the accounting treatment of QT to exclude profits and losses accruing from the APF which could enlarge the fiscal headroom by some £ 28 bln according to existing OBR estimates. But this would be too contentious, not least given the extent to which the APF had been reducing debt prior to 2022 (Figure 2).

Regardless, it does seem as if the Chancellor has only a small margin for error against the UK government’s debt-reduction rules and is still well below the average headroom available to his predecessors. This is something that the OBR has been very open about: Richard Hughes, its chair said the £ 13 bn budget headroom forecast in November was heavily exposed to changing assumptions on interest rates as well as data revisions and with “almost no detail” on how it intended to deliver public services after the election, when spending is projected to grow more slowly than the economy, leading to a significant squeeze.

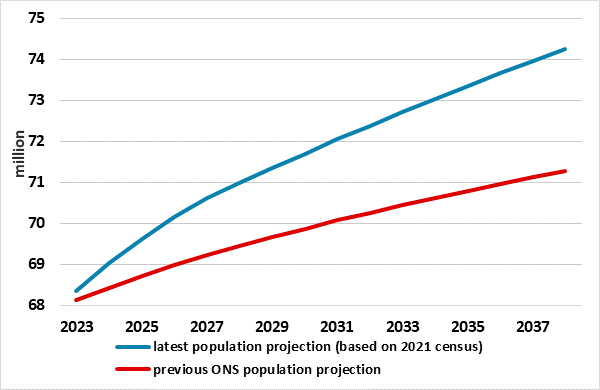

A Demographic Fiscal Rabbit Out of the Hat?

While politically damaging to the government given its immigration focus, the fact that the Office for National Statistics has markedly upgraded its population projections has clear potential fiscal reverberations. Those latest set of population projections, released last month, now suggest that the population is set to grow almost twice as rapidly by 2030 than previously projected, mainly due to the ONS assuming net migration averaging 315,000 in the long run, from around 245,000 previously.It is almost certainly that the OBR will incorporate these updated projections as it has always relied on the ONS’s long-term estimates for its population assumptions.

Figure 3: Population Projections Upgraded

Source: ONS

And with the population set to be 2.4% bigger by 2028-29 than the OBR assumed in November (Figure 3), nominal output would probably get a large lift too (we assume a rise of around 1.5% on the basis of the current participation rate of 0.63% persisting). This could boost nominal GDP by some £ 50 bln by the end of the projection period. Then applying the OBR’s projected tax-take for FY 2028-29 (ie 41.6% of GDP) means the government could get a permanent fiscal windfall of over £ 20 bln, albeit this estimate subject to many possible judgments the OBR could make, not least on the likes of productivity.

Given the political backdrop and the inter-related government focus on tax cuts, it would seem very likely that the Chancellor would use this added scope to cuts tax rates (income or national insurance) both to cover the continued freeze in tax thresholds and to prevent a new government getting a fiscal windfall