Eurozone: Monetary Messages Gaining More Prominence?

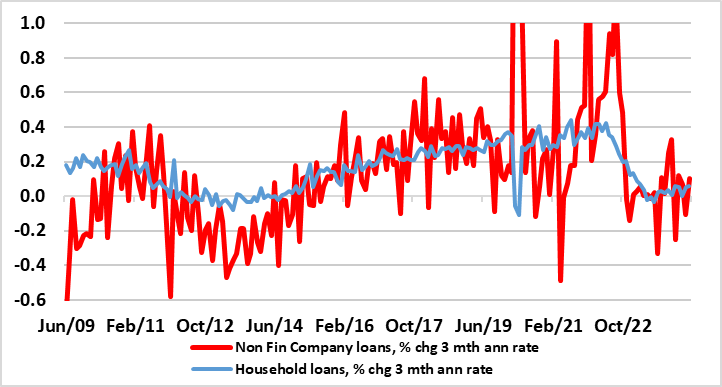

Amid speculation about the size and durability of any EZ real economy recovery, one important thing is still lacking. Indeed, monetary data remain weak; while money supply growth measures have turned positive what we think are the more important aspects, namely credit data remain feeble. Data this week showed adjusted credit growth slowing a notch to 0.8% y/y. But this masks clearer and persistent short-term weakness with 3-mth measures still near zero in terms of lending by both household and firms (Figure 1). This is all the more notable in week when ECB Chief Economist Lane used a keynote speech to underscore the central role played by monetary analysis, this acknowledgement being somewhat in contrast to the lip service such data gets at regular press conferences. The speech also gave more formal acknowledgement of the adverse repercussion of current ECB QT, corroborating themes we have been stressing for some time. Thus is all the more notable given the likely further restraint on credit levels that the ECB’s plans to reduce its balance sheet further may have.

Figure 1: Short-Run Credit Growth Measures Still Flat

Source: ECB

As Figure 1 shows, amid signs of a small recovery in money growth and deposits, there is little sign of private sector credit showing any appreciable pick-up. Admittedly, growth rates are no longer negative, as these 3-mth annualized measures highlight, but there is no discernible sign of any clear pick-up. Indeed, credit growth is still negative in real terms.

This is all the more notable given the ECB is starting to be more open about the extent to which its unconventional policies may be at least exacerbating this credit weakness. Chief Economist Lane admitted QT’s impact in in reining in bank deposits and credit. Unconventional monetary policy may thus be having a clear and more durable impact than the mere noise in the background as it is often portrayed. QE was very clearly highlighted for its positive effects. In this regard, outright central bank asset purchases lead to an increase in bank reserve holdings and banks respond by trying to minimise the costly associated liquidity surplus by creating credit in an effort to boost profitability. This mechanism helps explain the strong connection of credit with reserve creation in times of QE.

But the process also works in the opposite direction, where a withdrawal of reserves sets in motion a cumulative process by which credit and deposits shrink by a multiple of the original negative shock to the reserve holdings. As Lane underscores, this means that, in order to assess the implications of QT, it is important to trace all the implications of the central bank balance sheet contraction for asset prices and credit in an encompassing framework and to take into account the relation between central bank liquidity and bank intermediation capacity.

The Lane speech also acknowledged the extent to which the tightening in the current cycle has been amplified by banks being unwilling to lend as much as by a rise in the cost of credit. We highlight this as these are themes we have been stressing for some time and have been crucial to our downbeat assessment of the economic outlook. A discussion of them is all the more needed given the likely further restraint on lending that the ECB’s plans to reduce its balance sheet further may have. But it is also part of growing criticism of DM central banks in not having allowed monetary data analysis to play a more central and overt role in shaping policy and forecasts!