China Outlook: Headwinds To Growth

Bottom Line: Two of the normal drivers of China growth will continue to falter. Residential property investment will be restrained by the overhang on unsold properties; weakness of property developers and a sceptical household sector. Meanwhile, exports are being hurt by a shift of global supply chains, partially on fears of geopolitical tensions over Taiwan. With consumption reasonable rather than good, we see growth falling short of official desires for 5% in 2024 and 2025. Excess domestic production also means that inflation will struggle to get much above 1%, which means nominal GDP around 5% rather than official desires for 8%. Even so, concerns about the long-term debt/GDP trajectory will likely mean that the extra policy stimulus remains targeted rather than aggressive.

Our Forecasts

Source: Continuum Economics

Policy Stimulus Insufficient to Stop Slowing

China is facing a number of headwinds that will make 5% growth difficult to achieve in 2024. Key issues include:

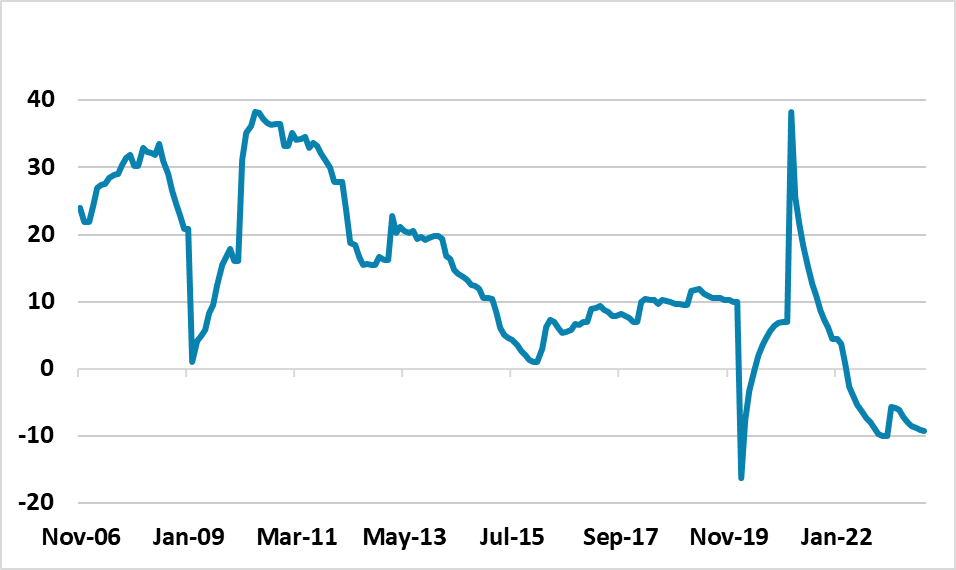

· Property construction downturn. China authorities have undertaken a number of measures, but none are game changers that materially changes sentiment towards property developers or sustainably increases demand for new houses. The Yuan1trn LGFV swap for local government paper is designed to stop a debt spiral, while a proposed Yuan1trn for affordable housing 2024-26 can absorb some excess supply but could reduce other lending by the financial system. Insufficient decline in house prices in 3 and 4 tier cities (here) is also an issue, as households know that a cheap enough house prices have not been established to produce a bottom in the market. Property developers are now moving towards acute distress and default, which will further shake confidence. Overall, we continue to look for an L shaped trajectory in residential property development though 2024-26, which will be an absolute negative drag on GDP – circa 1 to 1.5% of GDP.

Figure 1: China Residential Property Investment Yr/Yr (%)

Source: Datastream/Continuum Economics

· Exports and shifting supply chains. 2023 exports have been disappointing as the global economy slows, but a switch of China centric supply chains has also been a structural force depressing exports from China that will be sustained in the coming years. Global businesses want to make supply chains more resilient after the COVID crisis and Ukraine war, while the threat of a China/Taiwan war is also a push factor in reshaping supply chains. Despite the resilience of the U.S. economy in 2023, China exports have suffered but Mexico exports to the U.S. have surged due to near shoring. A similar pattern in bi lateral exports is evident in EZ trade figures, with China suffering at the expense of the U.S. Mexico/Turkey/Vietnam and India are all beneficiaries of some supply chains being shifted away from China. This is unlikely to change in 2024 and 2025, especially as the aftermath of January 2024 Taiwan presidential election will likely be increased gray warfare by China that increases geopolitical instability (here). Thus we see net exports contributing little to growth.

· Consumer spending. The good news is that post COVID services and tourism have had a great year in 2023, with the bad news being that housing related consumption has struggled. The post COVID pent up demand will likely now fade through 2024 and this leaves consumption on a slowing trajectory to reasonable rather than good growth. The normal boost to consumption from higher employment growth is not coming through as forcefully as usual, partially as private sector employers are uncertain as government policy is for state socialism rather than the pro-business era 1990-2019. Population aging is also an undercurrent, as the percentage of 20-40yr olds is less and consumes less in aggregate, while the wave of people retiring currently remains noticeable with associated lower consumption (here). Not enough is being done by China’s authorities to reduce high precautionary savings due to insufficient education/health/pension spending. Some support for households will come from the authorities’ forced reduction in existing mortgage rates, but overall consumption is likely to be reasonable rather than good in 2024. The same force will remain in play in 2025.

· Targeted rather aggressive policy stimulus. Some policy stimulus is helpful in the shape of the Yuan1trn for local government infrastructure construction and this is the main reason why we have revised up 2024 GDP forecast to 4.2% from 4.0%. Monetary policy stimulus though is measured and insufficient for an economy with two major problem sectors and with a large overall debt/GDP ratio. While China is not in balance sheet recession, the effectiveness of monetary policy has been hurt. Our central assumption is that this targeted approach will be sustained in 2024 and 2025, which should put a floor under growth but is not enough to push GDP growth up to 5%.

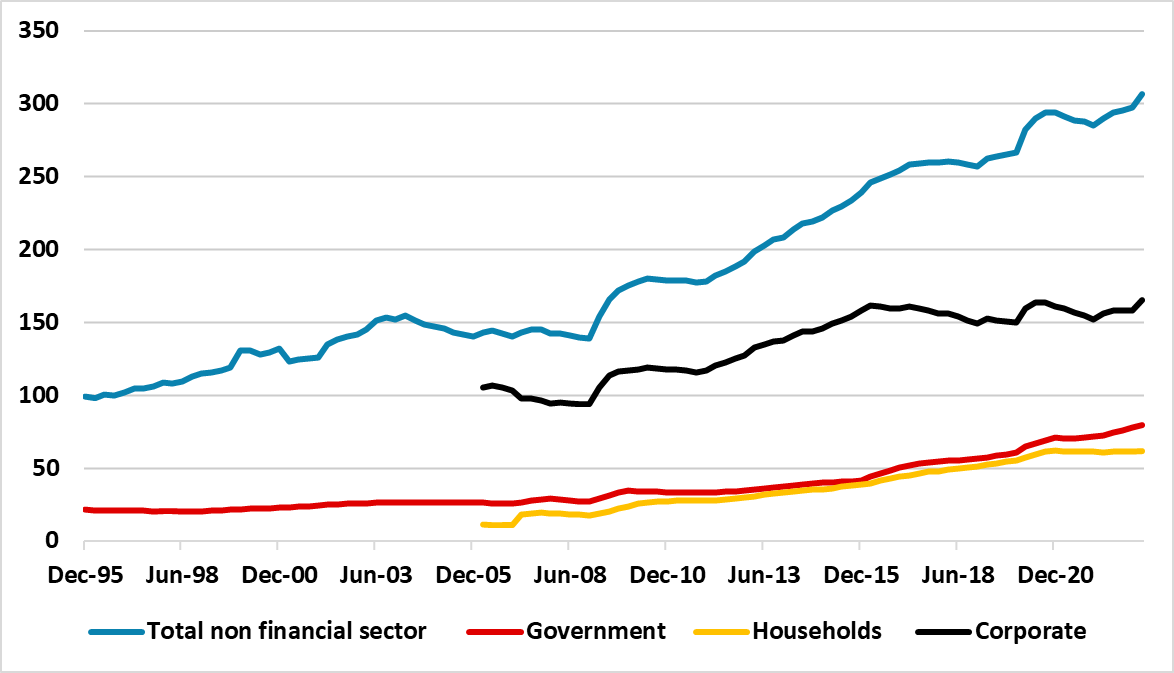

Figure 2: Government/Corporate and Household Debt/GDP (%)

Source: BIS/Continuum Economics

Source: BIS/Continuum Economics

Overall, we see 4.2% GDP growth in 2024 and 4.0% in 2025, as the headwinds to growth remain in placeOverall, we see 4.2% GDP growth in 2024 and 4.0% in 2025, as the headwinds to growth remain in place. Public sector investment and SOE activity will be reasonable, but are not enough with the structural headwinds for residential construction and exports, and consumers not firing on all cylinders. Additionally, China is making great progress on electric vehicle rollout; renewable energy transformation and expanding semi-conductor production. This is all supportive of China’s growth, but are not enough to outweigh the headwinds for China growth.

The other side of this process is that production capacity exceeds domestic consumption trends, which causes disinflationary forces and also lower hiring needs/wage inflation. Current core inflation reflects these dynamics. Though the depressing effect from falling pork prices will likely ebb in 2024, headline inflation is likely to only rise to around 1% due to these disinflationary influences and well below the authorities’ desires for 3% inflation. Thus nominal GDP will likely be around 5% in the next two years against official desires for 8% (5% GDP growth and 3% inflation).

Policy

The shortfall in nominal GDP could argue for more aggressive stimulus. However, China’s authorities are concerned that total non-financial sector debt/GDP could get too high and eventually cause a balance sheet recession like Japan in the 1990s. Additionally, a political bias remains towards supply side expenditure rather than cyclical or structural support for households (e.g. increased education/health/pension provision or later retirement age that could also sustainable boost consumption). This means a targeted approach to additional policy support will remain in place. This will likely see further fiscal stimulus in 2024 and 2025 of a moderate rather aggressive nature.

Additionally, some further monetary easing will likely be evident. We see a cumulative 30bps medium-term facility rate cuts slowly delivered over 2024, alongside two further 25bps reduction in the reserve requirement ratio (RRR). We then see policymakers getting nervous about the growth shortfall and cutting the MTF rate by a further 25bps in 2025. The Q3 PBOC report appears to heralding more emphasis on the price of money coming down and accepting that credit growth will slow to below 10% (as lending is targeted to growth sectors such as technology away from construction). This is a potential policy mistake, as previous experience has shown that countries with excess debt need to sustain the quantity of credit growth and reducing the price of money is less effective. However, the odds remain against China going to ultra-low interest rates and large scale QE via government bond purchases, both due to concerns that it could fuel the debt/GDP trajectory and also as they want to avoid a downward spiral for the Yuan (PBOC funding for policy banks’ lending should be regarded as credit easing rather than QE). The problem of wanting to control multiple targets means that China authorities will likely restrain themselves, with the cost being a growth undershoot.

However, China does not want to see a stronger Yuan, as that could undercut exports. Thus the bias will likely remain towards a softer Yuan, with intermittent periods of stability to ensure that the market does not get too pessimistic. Interest rate differentials against the USD will likely not narrow much in 2024, though they will in 2025. Even so, current 3mth and 10yr spreads with the U.S. are consistent with around 8.00-8.25 on USDCNY. We see the current bounce in the Yuan fading and a small to modest decline being evident in 2024.