Sweden Riksbank Preview (Nov 7): Rate Cuts Driven Increasingly by Weak Economy

A fourth successive 25 bp rate cut (to 3.0%) is widely seen at the looming Riksbank meeting (Nov 7), with the risk that it may even be the 50 bp move that was hinted at as part of the two further cuts advertised at the last (September) meeting. What seems clear is that inflation worries have subsided against a backdrop on below target recent CPI readings only to be replaced by clearer worries about the (still contracting) real economy (Figure 1). This is an interim meeting with no formal update of forecasts, so we think there will be no different policy guidance at this juncture. We still see the policy rate at or below 2.75% by year end and adhere to our long-standing policy rate forecasts of 2.25% by mid-2025, now the same as the Riksbank’s terminal rate but one we begin arrived at two quarters earlier. But deeper cuts are possible as even the Riksbank acknowledges (Figure 2).

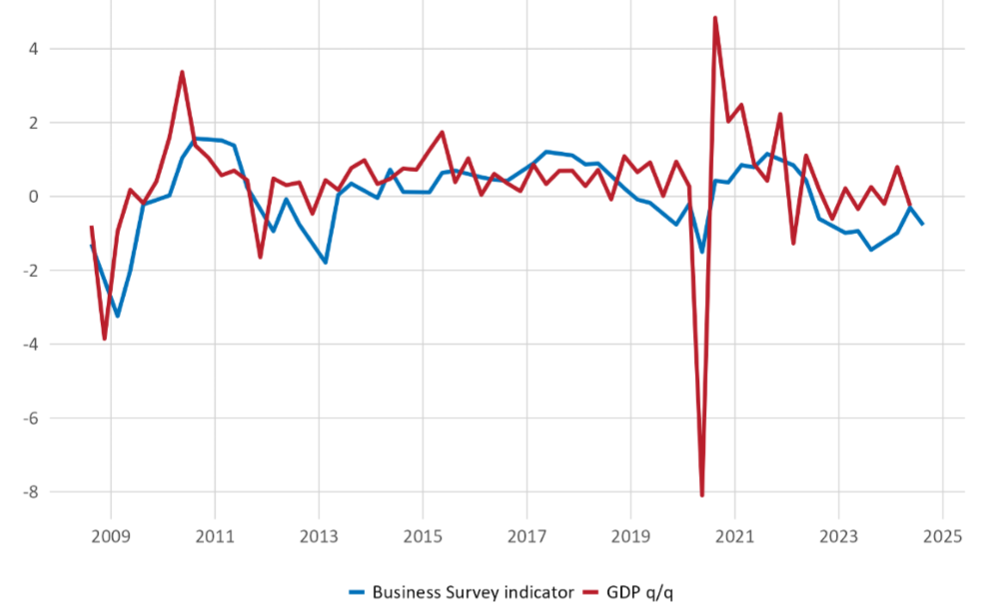

Figure 1: Real Economy Still Contracting

Source: Riksbank, Index figures and quarterly change in per cent respectively

Gloomy Real Economy News Persists

Indeed, it is clear that while lower inflation has provided the scope to ease policy in this speedier manner, the rationale is increasingly that from a weak economy. The latter is highlighted by a marked downgrade to the Riksbank’s’ 2024 GDP picture, offered at the meeting last month, partly offset by small upgrade to an above trend and what we think is an optimistic 1.9% 2025, albeit solely a result of the faster easing in its monetary stance bow being flagged and undertaken. But even the downgrade the Riksbank made to this year’s GDP projection (-0.3 ppt to 0.8%) looks optimistic, not least given the latest real economy insights. This included a flash Q£ GDP reading showing a further q/q drop (as opposed to the rise the Riksbank has factored in) and also a bleak message from the Riksbank’s own business survey published today (Figure 1). This noted that ‘the poorer outlook is most evident in the manufacturing sector, which no longer expects an improvement in the near term. The export industry is feeling the effects of weaker demand from the rest of the world, which is reflected in the continued fall in new orders. For the construction sector, the situation remains tough’ with the survey very much suggesting a total lack of pricing power for firms ensuing.

Policy Front-Loading?

Since the spring, it was very much a question of how fast, not if, as far as policy easing was concerned for the Riksbank, with policy thinking having been markedly reshaped this year. From the Board’s perspective, by initiating easing relatively early in May, it was both reacting to weak data (both real and price wise), but more notably in giving itself flexibility to pursue what it then thought needed to be a gradualist approach to further easing. That now has changed and increasingly radically with policy put into a faster gear to front-load, both a result of an undershoot of inflation (partly energy related but ever clearer in terms of short-run dynamics) but as suggested above increasingly due to a still weak economy which has failed to grow on balance since end-2021, albeit with clear quarter-to-quarter volatility.

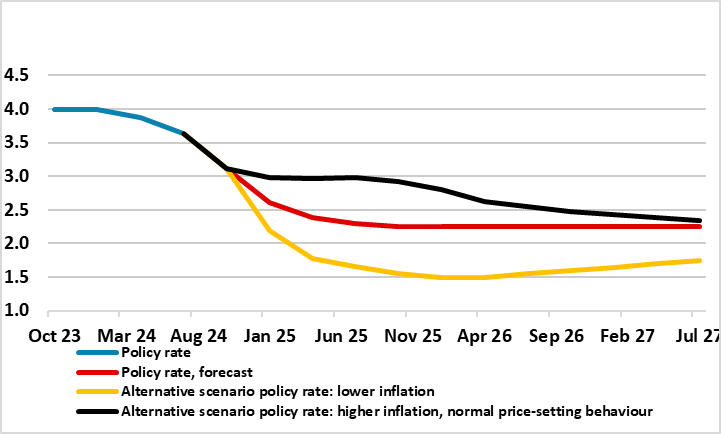

Figure 2: Alternative Official Policy Outlooks

Source: Riksbank

Terminal Rate Scenarios

Especially given the seemingly-feeble Q3 GDP backdrop, this reinforces our relative pessimism about the scale of the recovery. But even with the Riksbank pointing to the economy picking up and growing in 2025 at and then above trend at over 2% in 2026, this still generates a negative output gap of over 1% of potential GDP that diminishes but persists into 2027. We think this growth outlook is somewhat optimistic. But the point is that the Riksbank still accepts that even this more upbeat real economy outlook delivers price stability, if not a risk of a persistent slight target undershoot. Admittedly the updated MPR reined in growth expectation somewhat for the rest of this year but upgraded the profile after this year. This would reflect not only the faster easing but the fact that Sweden is far more sensitive to short-term rate changes given that the bulk of the housing market is still biased to variable rate mortgages.

The question is, if growth disappoints into 2025, will the Riksbank ease further than it is now flagging. This is entirely possible – indeed, the Riksbank scenario analysis suggests that the policy rate could drop below 2%, at least temporarily (Figure 2). Supposedly, this would have to be a result of the weaker growth backdrop accentuating disinflation, bit other factors may come into play, not least policy moves elsewhere which may result in a greater and unwanted appreciation of the currency than currently envisaged by the Riksbank.