China’s 2nd Tier Banking Problems

China’s residential property bust continues to feedthrough to some bank’s non-performing loans and financial stability. Even so, the latest PBOC financial stability report shows the percentage of high risk rated banks has not increased over the last 12 months, while China authorities early warning system/corrective action and forced takeovers are helping to manage the weakest institutions. However, IMF stress tests show that an adverse economic scenario could impact a lot of 2nd tier city commercial and rural banks outside the 19 domestically systemically important banks. The 2nd tier banking problems need continued monitoring.

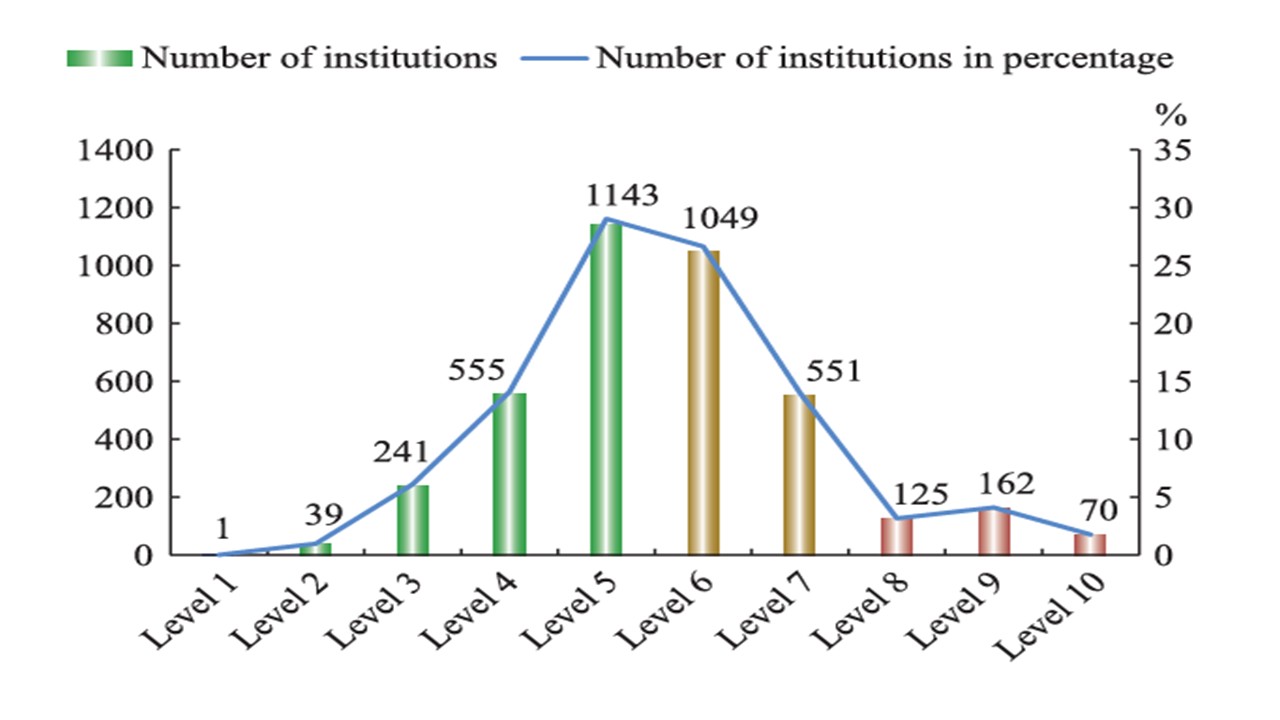

Figure 1: PBOC Ratings of Banking and Financial Institutions

Source: 2024 PBOC Financial Stability Report (here)

The 2024 PBOC financial stability report, released in mid-October, shows that 357 banks accounting for 1.78% of total banking system assets are in the red ratings zone (Figure 1), which are high risk and require corrective action. This is very similar to the numbers in the red zone in the 2023 PBOC financial stability report, with the number of financial institutions has decreased by 77 to 4490 mainly due to forced takeovers and mergers. The details in special topic 3 show that the red zone banks are mainly the smaller rural and village banks, rather than the 19 domestically systemically important banks (D-SIB’s). However, 11.5% (14 of the 125) city commercial banks are in the red zone, which is a cause for concern and need ongoing monitoring.

China’s authorities remain alert and this is clear once again in the 2024 financial stability report. The PBOC has an early warning system to see any problem arising at institutions. Secondly, the PBOC has undertaken action to improve high risk banks and has also been rolling out tougher mandatory prompt corrective action in a number of regions. Thirdly, the authorities force weaker banks to be taken over or forced into mergers to limit damage (e.g. Liaoning Rural Commercial Bank absorbed 36 local small rural lenders in June 2024). Fourthly, the strong six state major banks have seen an extra Yuan500bln of equity capital injected to allow increased lending and the ability to takeover weaker institutions. Finally, awareness of China’s deposit insurance has increased, helping to reduce the risk of deposit bank runs.

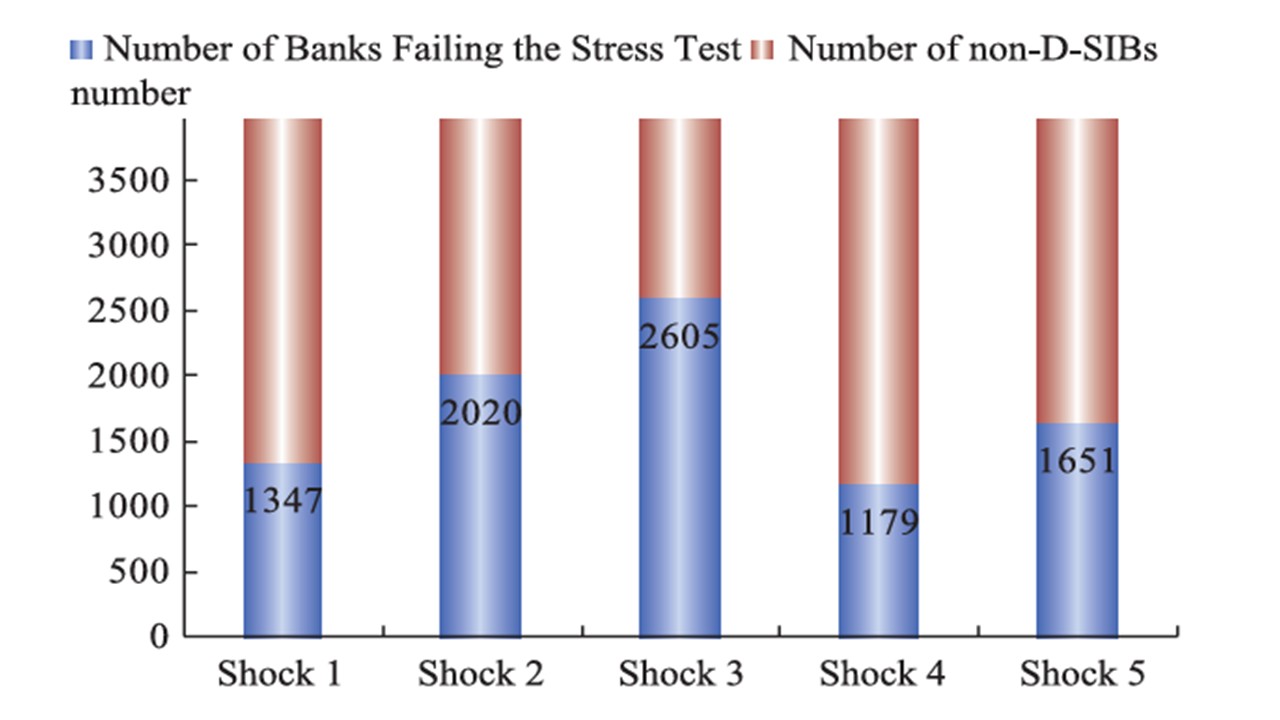

However, the latest PBOC financial stability report did not repeat last year’s stress tests, which were a cause for concern. The 19 D-SIB, accounting for 71% of total banking assets, were largely fine in the 2023 mild and modest stress tests, but the 3966 non D-SIB’s could see wider spread capital shortfalls on a moderate or severe risk scenario (Figure 2). This would not just require selective takeovers and mergers, but also large-scale central government recapitalization and takeovers by the six largest banks and government asset management companies (which were used to bailout the large banks in 1997-2003).

Figure 2: 2023 PBOC Stress Tests

Source: PBOC Financial Stability Report 2023 Special Topic 4 Stress Tests Shock 1 NPL up 100; Shock 2 NPL’s up 200%, Shock 3 NPL’s up 400%, Shock 4 50% of Special Mentioned Loans converted to NPL’s, Shock 5 100% of Special Mentioned Loans converted to NPL’s.

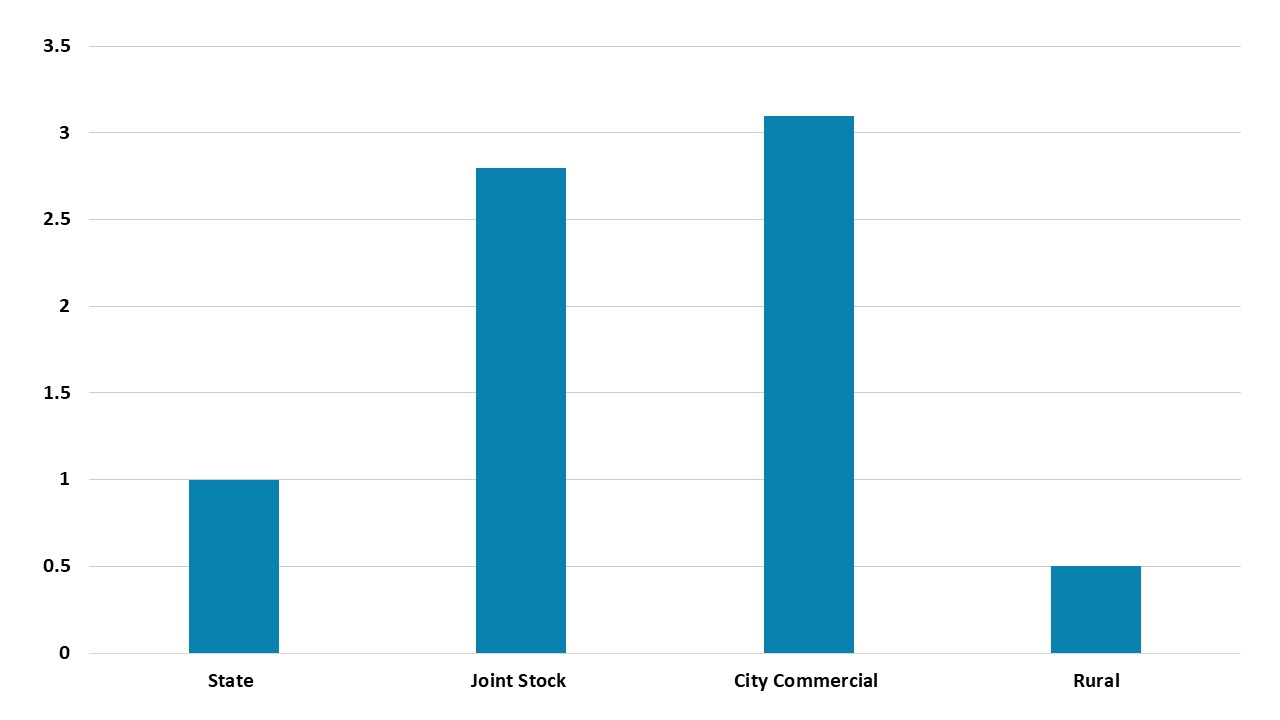

It was interesting that the IMF FSAP April 2025 stress test (Figure 3) also raised some concerns about the weaker joint stock and city commercial banks. China authorities have fiscal space to fill this equity shortfall if an adverse scenario occurs, e.g. sub 3% GDP growth/surging NPL’s. In such case, rescues and forced takeovers would have to accelerate significantly. All this underlines that the long and controlled restructuring in weaker banks could worsen dramatically with an adverse economic shock. A lot of this relates to the residential property market crisis, where the long decline in house prices is also undermining bank assets. Meanwhile, weakness in sections of the banking system act as a headwind to credit supply for some households and businesses.

Figure 3: Total Capital Shortfall (% of Risk Weighted Assets 2023)

Source: IMF FSAP April 2025 (here)

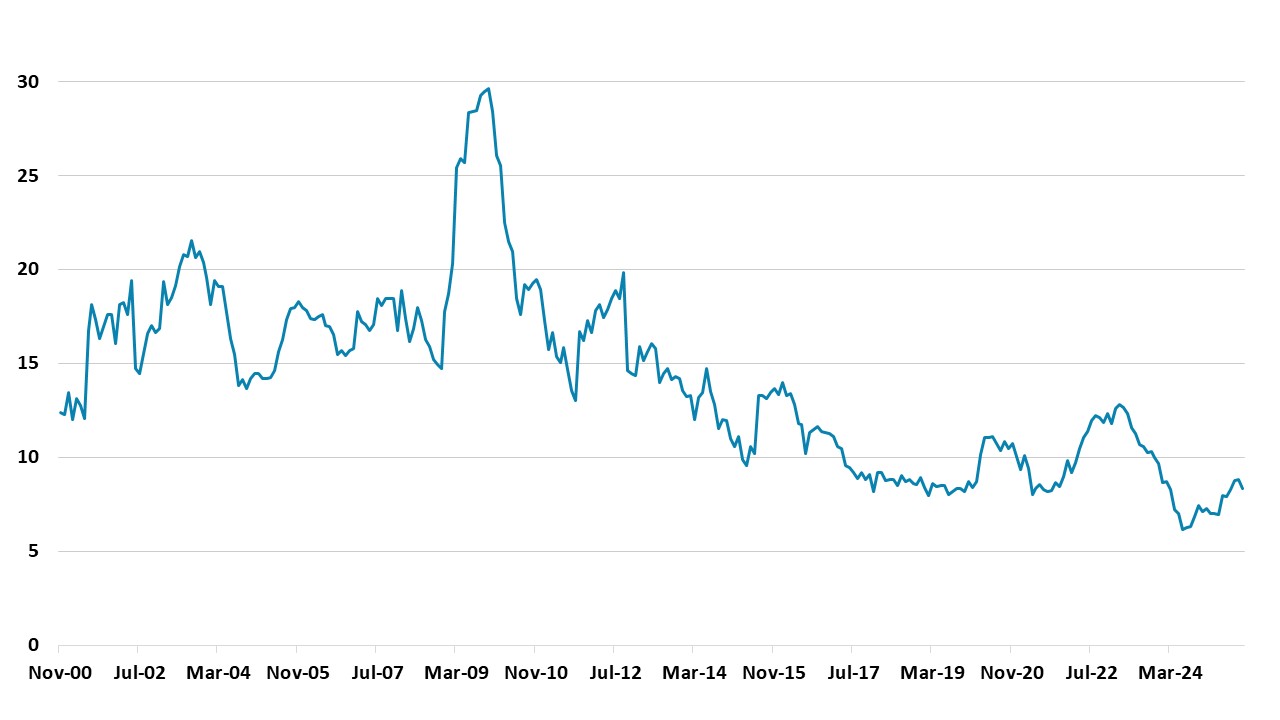

Figure 4: China M2 (Yr/Yr %)

Source: Datastream/Continuum Economics

China’s M2 growth has picked up recently (Figure 4), as the residential property market has become less adverse. The government has injected Yuan500bln equity capital into the largest state owned banks while the government has also provided a 5 year Yuan10trn debt swap for local government and LGFV’s. However, we would prefer to see close to 10% M2 growth to be confident of 5% real GDP growth, given the normal relationship between M2 and real GDP.

China also has a credit demand problem. Firstly, though the situation is becoming less acute in the housing sector, sentiment is still weak with a multi-year overhang of property; declining house prices and shaken confidence in builders. This will take years to repair, especially given households’ desire not to increase debt burdens. Secondly, private sector companies are less willing to invest than the 1990-2019 period, both due to economic volatility and a lingering sense that China authorities do not favor the private sector – the 2021-22 crackdowns are fading, but the authorities are still not fully pro-business. Thirdly, LGFV’s weak debt is massive due to poor investment decisions. The latest IMF FSAP in April 2025, estimated that 39-45% of debt was in trouble. The IMF has not taken account of the Yuan10trn government debt swap that largely deals with the weak LGFV problems, but this scales in over 5 years and weak LGFV’s may not quickly switch from paying debt down to new normal borrowing.

Overall, we remain watchful of money and credit trends, but remain concerned that money supply growth is insufficient to achieve 5% real GDP growth. We currently look for 4.5% GDP growth for 2026.