ECB: Life in the Not So Fast Lane!

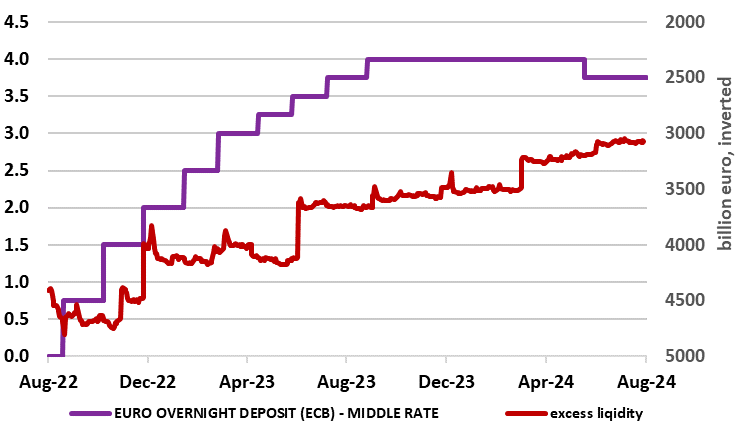

A keynote speech by ECB Chief Economist Lane at Jackson Hole over the week-end suggested that further monetary easing is on the way but in a path that has to steer between the risks of moving too fast against those from moving too slowly. Very clearly he implied that policy will still have to remain restrictive for some time. But with policy rates very much well above what most consider to be neutral, policy would remain restrictive even with around 150 bp of added official rate cuts. But this is not the whole story as Lane acknowledged that ECB balance sheet reduction, via its impact on continuing to reduce banking sector excess liquidity (Figure 1), may only strengthen the policy transmission mechanism. This indicates that the ECB’s planned further QT may temper the impact of the likely further conventional easing, in turn suggesting that gauging what would be a neutral policy stance is oversimplified by merely looking at where official policy rates are.

Figure 1: Rate Hikes Accompanied by Marked drop in Excess Liquidity

Source: ECB

In what were typical guarded ECB comments, Lane underscored that the return to target is not yet secure. In particular, he reiterated that the monetary stance will have to remain in restrictive territory for as long as is needed to get inflation back to target target. He balanced this by stressing too that any return to target needs to be sustainable to a degree that a rate path that is too high for too long would deliver chronically below-target inflation over the medium term and would be inefficient in terms of minimising the side effects on output and employment. All of which begs the question as to what constitutes policy restriction.

The Natural Rate Debate

Very clearly among policy makers is the (Wicksell-type) view that a neutral rate very much equates with the so-called natural rate, ie that rate consistent with price and economic stability and is a key concept in monetary economics as it offers an assessment of the stance of monetary policy. Of course, gauging what rate(s) to use to assess policy is complicated; the most relevant market rates for households and firms are not the policy rates set by central banks, but rather an array of rates across the whole yield curve, albeit in a bank credit dominated economy such as that of the EZ shorter-term rates would be more important.

But there are further complications as the policy transmission mechanism will be affected also by how and when banks change their credit standards – ie affecting the supply of credit as well as its cost. In this regard, it is clear that banks have acted much faster in tightening credit standards in the current cycle than previously, thereby buttressing the monetary policy transmission mechanism. But there are other issues too, not least the impact of unconventional policy that has seen the balance sheets of central banks soar and, more recently, fall back sharply.

Not So Excess Liquidity

In the EZ, this process has been marked so that central bank excess reserves have declined by more than a third since the peak reached in the second half of 2022. This has mostly been the result of the repayment of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO) but will continue nonetheless through the (further) reduction of the ECB’s bond portfolios. This has led to a marked fall in excess liquidity in the EZ banking system (Figure 1). And as Lane acknowledged, ‘from a macroeconomic perspective, the transition from a high-reserves environment to a lower-reserves environment can trigger a shift in the risk-taking strategies of banks’.

Indeed, he admitted something we have been suggesting for some time, namely that this contraction in liquidity may have contributed to the relatively-strong decline in EZ lending volumes during this tightening episode. In particular, estimates by ECB staff suggest that banks with lower excess liquidity are more likely to reduce their supply of credit in response to policy rate hikes, and the increase in their lending rates is likely to be larger. This means that, as aggregate liquidity shrinks - as is likely amid QT plans - the transmission of the restrictive monetary policy stance to bank lending may strengthen further.

NB: we are aware of the planned changes to the Eurosystem’s operational framework scheduled as of Sep 18 which will see the rate on the MROs and the rate at the MLF will be adjusted such that the spread between the rate on the MROs (main refinancing operations) and the DFR (deposit facility rate) will be reduced to 15 bp from the 50 bp currently, and the spread between the MLF (marginal lending facility) rate and the rate on the MROs remain at 25 bp. The intended relatively narrow spread of 15 bp between the rate on the MROs and the DFR is aimed at limiting the potential upward pressure on money market rates and set incentives for banks to borrow liquidity in our operations as our balance sheet normalises.

Policy Implications

In other words, any easing in financial conditions emanating from future conventional easing may be (at least partly) offset by QT and that assessing the policy stance by looking at actual policy rates is a marked over-simplification. To what degree the ECB council majority will be sympathetic to this view is unclear and we are not changing our policy outlook of two more 25 rate cuts this year and a further 100 bp in 2025. But assessing the role of QT helps explain why we continue to see sub-consensus and sub-ECB thinking GDP growth ahead and with greater downside risks.