Country Insights: Fiscal Policy in Emerging Markets

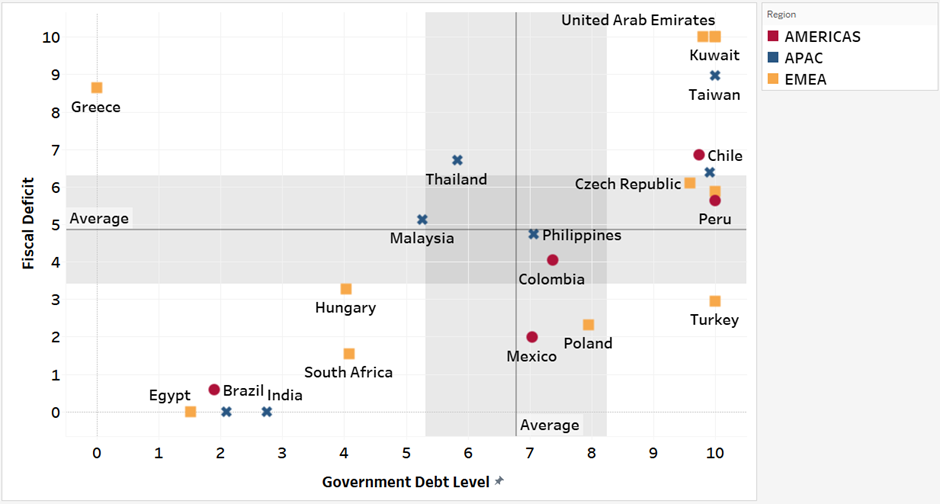

The latest update of our Country Insights model ranks the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait (KWT), and Taiwan (TWN) as the strongest performers in our Fiscal Policy’s sub-factors among selected emerging markets. Conversely, Egypt (EGY), Brazil (BRA), and China (CHN) rank among the weakest within this group.

The Fiscal Policy factor measures a government's ability to maintain fiscal discipline and consists of two sub-factors: government debt level and fiscal deficit. The first assesses the absolute debt level, its trajectory, and stability, while the second evaluates the government's track record in implementing sound fiscal policies. These indicators allow us to compare fiscal health across emerging markets and identify potential risks and opportunities.

“The debt crisis facing many developing countries is reaching new heights not seen in more than two decades resulting in devastating development trade-offs” is a statement of a recent United Nations Development Program’s policy paper (here). Indeed, over the last fifteen years, emerging markets have experienced a significant rise in public debt. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the general government gross debt for emerging markets and developing economies increased from 37% of GDP in 2010 to a projected 72% in 2025, nearly doubling within this period. For comparison, debt in advanced economies increased by 14 percentage points to 111% in the same period.

While each country has unique economic and institutional conditions, several common factors contribute to high debt levels in weaker-performing economies. Institutional weaknesses often lead to irresponsible fiscal management, while a lack of revenue diversification can increase vulnerability to external shocks. High interest rates and currency depreciation further exacerbate debt burdens, particularly for countries with large external debt.

Figure 1 illustrates that, despite these pressures, not all emerging markets face severe fiscal challenges. Some have maintained strong fiscal positions, but global economic and geopolitical shifts pose new risks. As we enter an era of weaker global trade growth and slower globalization, emerging markets—many of which rely on commodity exports—must adapt their fiscal policies to mitigate these risks. In this regard, the IMF, in its latest Fiscal Outlook, highlighted that EM can strengthen their fiscal position by broadening tax bases, limiting exemptions, leveraging digital tools for tax administration, cutting excessive wage bills, streamlining social programs, and phasing out subsidies.

Figure 1. Fiscal Policy Sub-Factors Scores in Selected Emerging Markets

Source: Continuum Economics

Note: 10 represents the maximum (and best) score and 0 represents the minimum (and worse) score.

One of the strongest performers in terms of government debt levels and fiscal deficits is the UAE. The IMF forecasts the country's general government gross debt at 31.4% of GDP. While this marks an increase of 15.3 percentage points since 2015 and 26.9 percentage points since 2005, much of the rise in debt can be attributed to the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to lower oil revenues and the implementation of fiscal stimulus measures. As a result, debt levels increased from 26.8% of GDP in 2019 to 41.3% in 2020. However, the UAE has since successfully reduced its debt, with a downward trajectory expected to continue for the remainder of the decade.

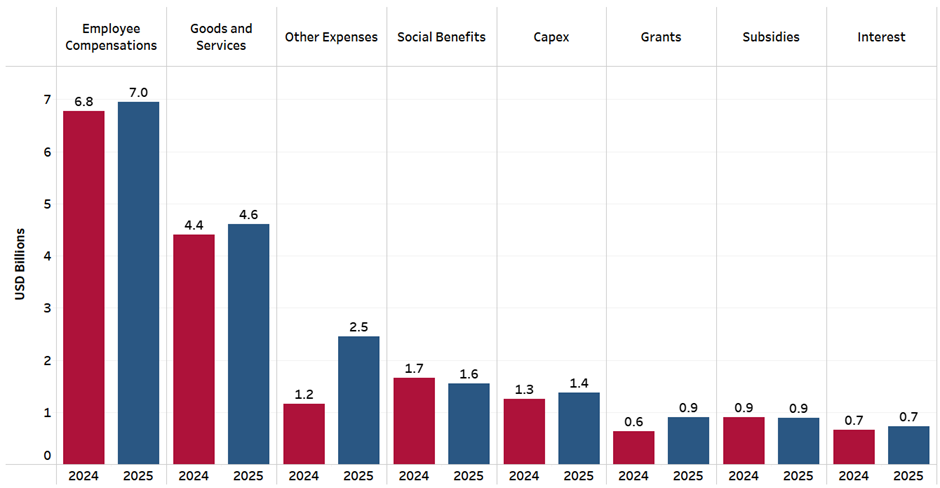

The UAE has taken steps to contain current expenditures, gradually phase out subsidies, and expand its tax base; for instance, the country introduced a Domestic Minimum Top-Up Tax of 15% for multinational enterprises with consolidated annual revenues exceeding EUR 750 million. However, while the IMF’s Article IV report acknowledges these efforts, the UAE’s FY 2025 budget tells a more complex story (Figure 2). Although subsidies are set to decline by 1.2% and social benefits by 6.5%, spending on employee compensation and goods and services are expected to increase by 2.6% and 4.6%, respectively.

Figure 2. UAE 2025 Budget Expenditure by Category

Source: Continuum Economics / UAE Ministry of Finance

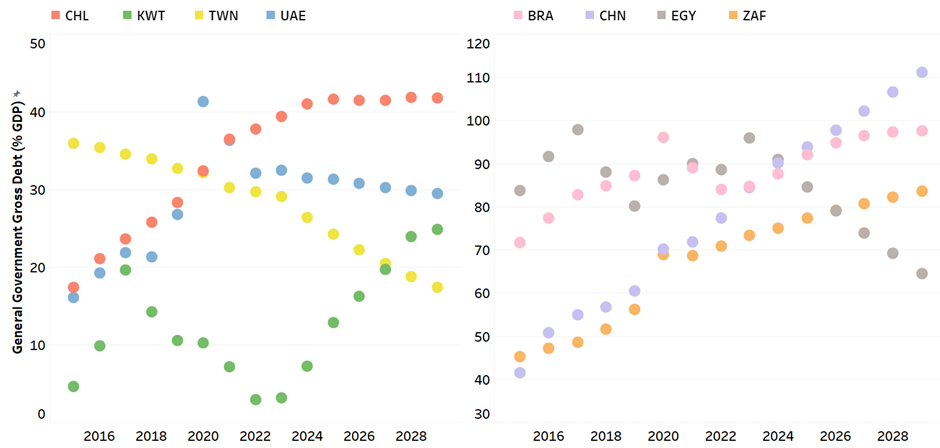

Kuwait is another strong performer, though its fiscal policy present challenges. While its general government gross debt remains low at 12.9% of GDP as per the IMF, it is on an upward trajectory, with projections reaching 24.8% by 2029 (Figure 3). The low debt level is largely due to the Public Debt Law passed in 2017, which capped public debt issuance. However, Bloomberg recently reported that Kuwait may soon be able to sell debt for the first time in eight years, potentially raising USD 65 billion over 50 years if new legislation is approved.

Moreover, Kuwait's general government overall balance is projected to remain stable at around 24% of GDP—including estimated Sovereign Wealth Fund investment income and State Owned Enterprise (SOE) profit transfers—over the next five years. However, the central government deficit is expected to rise from 7.9% to 8.8% of GDP. To address this, the government has proposed tax reforms, including levies on harmful goods such as tobacco and sugary beverages and a corporate tax on multinational enterprises similar to that of the UAE. Nonetheless, the 2025/26 budget allocates approximately 80% of expenditures to salaries and subsidies, leaving limited room for capital investment, signaling the need for further fiscal adjustments.

Figure 3. General Government Gross Debt (% GDP)

Source: Continuum Economics / International Monetary Fund

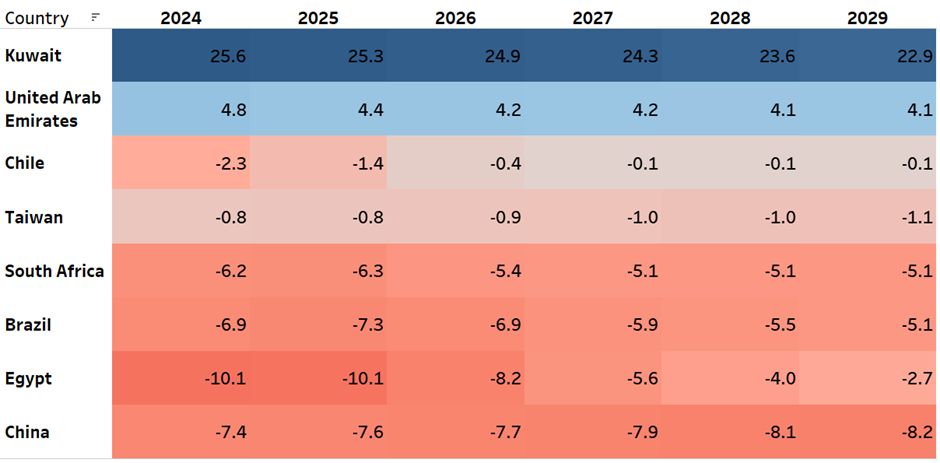

At the other end of the spectrum, Brazil and South Africa score poorly on both government debt level and fiscal deficit metrics (Figure 1). The IMF estimates Brazil’s general government gross debt at 92% of GDP in 2025, rising to 97.6% by 2029. South Africa’s debt trajectory is equally concerning, with debt tripling to 77% of GDP by 2025 since 2008. Both countries also face substantial fiscal deficits—South Africa’s general government deficit is projected at 6.3% in 2025, while Brazil’s stands at 7.3%, declining to 5.1% by 2029 (Figure 4). These trends underscore persistent fiscal imbalances, high public spending, and economic stagnation.

In Brazil, President Lula announced a fiscal program in November 2024, but investors remain skeptical. We discussed (here) that the plan focuses on capping public spending growth rather than pursuing deeper fiscal consolidation, leaving concerns about long-term debt sustainability. Brazil’s fiscal difficulties are long-standing, driven by extensive social programs, high pension costs, and structurally high interest rates. In addition to these issues, the country faces a complex tax system and a challenging business environment.

Factors that need to be followed in the next two years include the increase in debt-related expenditures and the upcoming presidential elections. Indeed, the Treasury estimates that the share of debt linked to the benchmark Selic interest rate will account for 48% - 52% of total debt this year, up from 46.3% in 2024. This becomes particularly relevant considering our expectations on the BCB’s tight monetary policy, which would further increase fiscal pressure – as we highlighted and discussed (here). Additionally, while it remains uncertain whether President Lula will run for reelection in October 2026, his potential candidacy could add additional pressure to the fiscal landscape. For instance, during his 2006 reelection bid, general government total expenditure (% of GDP) reached 42.6%—the highest of his four-year term.

In South Africa, over the last few years, the debt trajectory has deteriorated significantly due to consistent revenue shortfalls, unplanned bailouts for SOEs, and rising debt servicing costs. The government has struggled to curb debt growth, largely due to subdued economic growth and volatile commodity prices. In response, the authorities introduced expenditure ceilings in 2012, increased certain tax rates, and reduced capital investment. However, these measures only partially corrected the primary balance and failed to slow overall debt accumulation due to escalating interest payments. Stronger fiscal rules, particularly debt ceilings, could enhance debt sustainability and policy credibility.

The October 2024 Budget highlighted worsening fiscal deficits and growing debt despite fiscal consolidation measures, with Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana warning that sluggish growth and external risks would keep tax revenue under pressure. However, improved electricity supply and investor confidence following the coalition government’s formation were cited as positive economic factors. More recently, the February Budget was postponed due to disagreements over proposed tax increases, notably the plan to raise VAT from 15% to 17%. Our view (here) is that to address fiscal challenges, South Africa should focus on strengthening tax collection, reducing debt servicing costs, and reinforcing institutional fiscal frameworks. The IMF recommends wage discipline, SOE reforms, and stricter government procurement controls to improve fiscal sustainability.

Figure 4. General Government Overall Balance (% GDP)

Source: Continuum Economics / International Monetary Fund

Note: -ve is a deficit and +ve a surplus

Please refer to the following link (here) to access our full Country Insight Scores.