BoE Preview (Mar 20): Being Careful the New Watchword

Having so far cut a modest 75 bp, the BoE rate cut last month was delivered with a clear(er) degree of action, by at least the MPC majority. But those implied MPC divisions probably reflected increased uncertainty enough for the BoE to have altered its rhetoric somewhat to stress the need for policy to be framed carefully as well as gradually. This very much points to stable policy (Bank Rate still at 4.5%) at this looming March meeting, with it increasingly likely that the MPC majority envisages rate cuts not faster than every quarter this year and a little further into 2026. Given what we think is a flailing real economy backdrop, which growing global trade tensions may only accentuate, BoE easing may yet come faster and further as the BoE reassess its optimism about growth and upgrades its estimate extent of slack – particularly in the labor market (Figure 1).

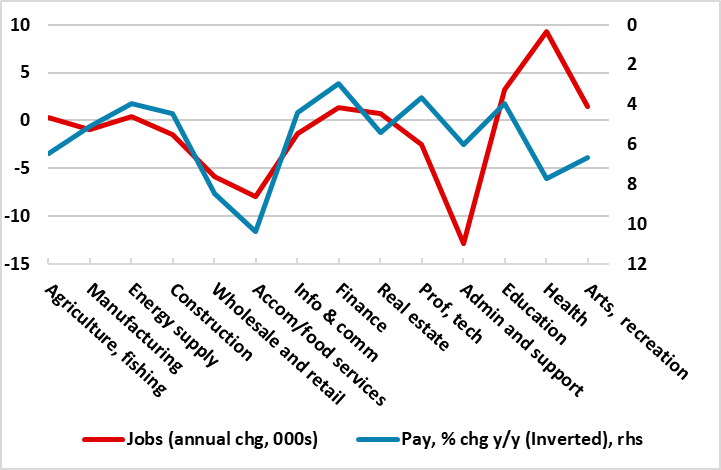

Figure 1: Sectors Facing Highest Pay Growth Seeing Clearest Job Shedding

Source; HMRC

The last set of BoE forecasts were notable for one possibly major thing – an assumption that underlying growth has fallen, possible to under 1%, much to do with the labor market. This does not explain all of the higher inflation profile which it pointed to in last month’s Monetary Policy Report that now only delivers a below target outcome into 2028 – the higher rates projected this year reflect higher energy and regulated prices. Admittedly energy prices have fallen back since and markedly so but this is unlikely to calm what if anything may be a greater inflationary concern among the MPC majority. Indeed, pseudo MPC-dove Dep Gov Ramsden has very much flagged an increased worry about possible inflation persistence based around recent wage data, albeit what we think are still dubiously accurate ONS numbers.

Labor (Market) Pains

It is a little ironic than that the next MPC decision will arrive the same day as the next set of labor market numbers. This data release, now encompassing updates not just from the long-standing ONS but also real time figures from the HMRC which we suggest are more authoritative data, show that employment is continuing to contract. Indeed, those payroll data produced by the HMRC, have now show six m/m falls since the level of payrolls peaked nine months ago, a marked contrast to the 1.4% increase official data suggest has occurred in the last year. More notably, amid fiscal strains, non-health public sector jobs have now started to fall too, compounding what has been an ever clearer haemorrhaging of jobs in private services, thereby suggesting that cost pressures (now accentuated by the looming increase in employee National Insurance Contributions and the actual rise in the minimum wage) have already affected the labor market severely.

But Labor Market is Doing Its Job!

This already seems to be happening, but possibly as much to already rising pay bills as to the threat of even higher labor costs to come. Indeed, as Figure 1 illustrates, the labor market is working as it should do, with sectors where pay is the highest seeing falling payrolls as companies try to adjust to already high wage bills by curbing jobs to limit the rise in labor costs that otherwise would either/both hit profit margins and/or raise the prospect of higher consumer prices. This is one the main reasons why we think he BoE is too concerned about the overall inflation outlook as (to us) we see companies are already acting to rein in their labor cost bills for fear that raising prices may only service to reduce demand. Indeed, there is already a clear and inverse relationship between employment changes and pay growth, the exception being health where government spending initiatives are both trying to repair real pay and actual output in the sector.

In other words, the BoE does not think that the downgrade in its GDP forecast to 0.75% (2025) is a reflection of weaker demand. Given that we share the 2025 overall outlook but where we also think the labor market is much weaker than the BoE is assuming, we are also skeptical about the economy then recovery to 1.5% through both 2026 and 2027, not least given the added threat posed by a trade war.

Scenario Shifting

Admittedly, the BoE is also aware of these risks, hence why it believes the outlook is more uncertain and enough so that it has to suggest that policy will have to be conducted carefully as well as gradually - with a clear debate about the wording of guidance evident from the minutes. This may explain the dissents and may reflect greater divisions with the MPC than a mere 7:2 split would suggest. What is clear is that the MPC is still keen on offering alternative scenarios. Hitherto, the first case saw remaining persistence in inflation dissipate quickly as pay and price-setting dynamics continued to normalise following the unwinding of the global shocks that had driven up inflation. In the second case, a period of economic slack might be required to normalise these dynamics fully. In the third case, some inflationary persistence might also reflect structural shifts in wage and price-setting behaviour. It seems that the MPC majority is now leaning more toward the latter two scenarios, hence a more hawkish leaning. However, we think that real economy consideration will come increasingly to the fore in coming months both by a weak data backdrop (now including survey data suggesting a hitherto solid construction sector has gone into reverse) and where the fiscal stance is likely to become an issue as the government considers tightening welfare payments in order to meet fiscal goals.