Eurozone Outlook: Downside Risks or Downside Reality?

· It does seem as if EZ activity expectations are being pared back in line with our below consensus thinking, most notably for next year. The result is that while the economy has been growing afresh it is doing so timidly, with downside risks persisting through 2024 and 2025 and where some such risks may be materializing as effectively sizeable downgrades in ECB growth projections suggest.

· This supports our long-standing and still-below consensus HICP outlook in which headline inflation is seen easing below target temporarily in H2 2024, with the core rate (still worrying the ECB) likely to follow and a sustained drop then occurring through 2025. This picture has persuaded the ECB to continue easing and we forecast a further 25 bp of official rate cuts later this year and more (100 bp) to follow in 2025.

· Given the growing likelihood of even lower official rates, a banking crisis is a low to modest risk save for a possible fresh fiscal flare-up. Perhaps the main risk is that interest rates cuts may be larger and/or faster than we have assumed as the lagged monetary developments and fiscal policy prove more restrictive while global growth disappoints.

· Forecast changes: Compared to the last outlook, we have (yet again) largely retained the overall EZ growth outlook, with a fragile recovery for 2024 that may now result in below trend-type growth in 2025. More notable, is the hardly-revised and still-soft EZ HICP inflation outlook in which the target is undershot on a sustained basis into 2025. As a result, we have again retained our ECB policy rate forecasts for a third successive time.

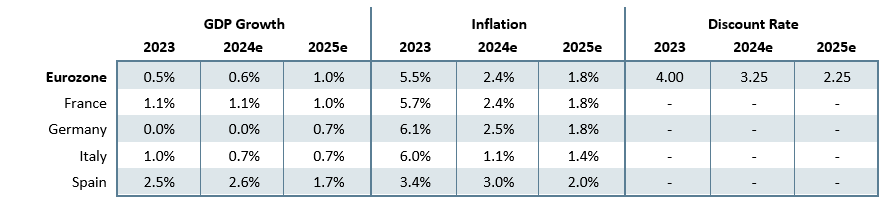

Our Forecasts

Source: Continuum Economics, Eurostat

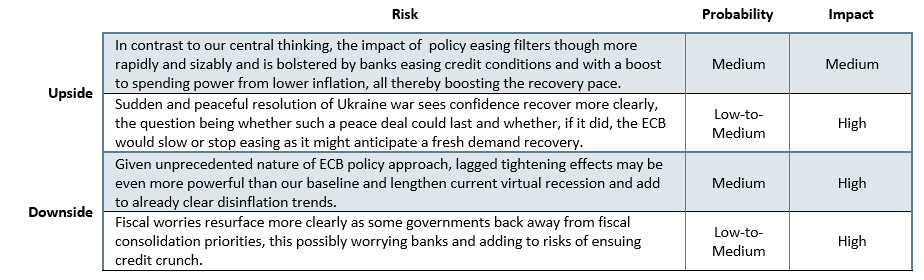

Risks to Our Views

Source: Continuum Economics

Eurozone: Activity Diverging Geographically?

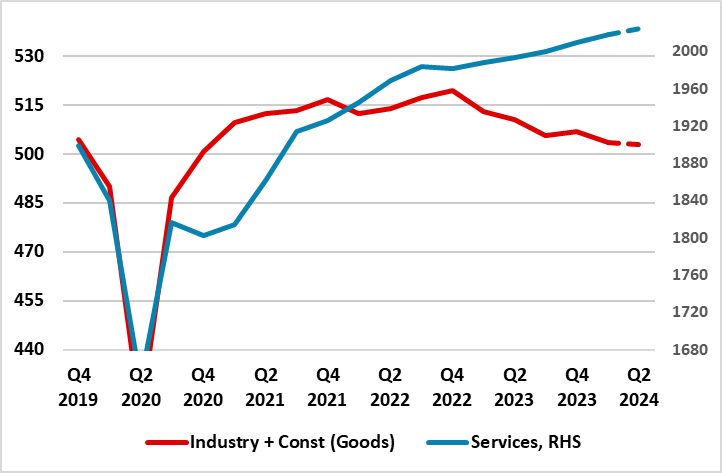

For some time, the EZ economy has been facing downside risks but they may now be materializing. The fact that growth rates among the EZ main economies have diverged even further of late (Spain robust, Germany contracting afresh) actually reflects a marked disparity in growth rates between strong services and persisting declines in goods output, this evident in both survey data as well as official national account data (Figure 1). In itself this is not troubling, not least as services (on average of around 70% of EZ GDP) are a far more sizeable component of GDP, but where the stronger economies have a relatively higher share. But recent survey data are increasingly suggesting weaker activity, and now including services to a degree that imply that the support the sector has given the whole EZ economy through H1 this year may have dissipated, if not reversed. Indeed, GDP growth could even turn negative this quarter, despite the boost that the Olympics may have had on French activity. At this juncture we think this is a blip rather than a fresh and weaker trend but is nevertheless indicative of the weak underlying growth picture we have been flagging for some time. Indeed, while upward revisions to H2 2024 have led us to upgrade the 2024 GDP outlook by a notch - but still to a below consensus 0.6% - we have pared back the 2025 outlook by 0.2 pp to 1.0%, both below par and mainstream thinking.

Some of this weakness reflects a belated recovery in imports, one partly offset by an inter-related recovery in inventories, one question being the extent to which the latter proves to be involuntary. But this will still be part of what may remain a soft final domestic demand outlook. This increasingly reflects what may be greater fiscal consolidation measures from several countries. It also involves consumer spending growing this year little more than the 0.5% pace seen last year and with little pick-up into 2025, but mainly a drop in overall capex that will be hardly repaired next year. Tight financial conditions (still very much evident in weak private sector credit and deposits) are the main cause of the capex weakness, accentuated by still wary company thinking and banking sector reservations about lending. Banking reluctance is also both a cause and reflection of (admittedly less marked) house price weakness but this is weighing on consumer spending both directly and indirectly. Notably, this domestic weakness comes in spite of a solid labor market, with current jobless rates at record lows. This partly reflects companies hoarding labor, which suggests that any recovery will not be as employment rich. But there has also been healthy rise in the workforce (actually to both higher and faster levels than pre-COVID), this being somewhat unique to the EZ. More notable is that the rise is very much dominated by an increase in the supply of younger workers, these much more likely to seek new jobs in pursuit of better remuneration, this possibly explaining the slowing in a whole array of wage pressure indicators of late – very much to below ECB thinking and likely to restrain spending power growth.

Otherwise, the anticipated recovery in imports into 2025 as well as what may be weaker global economy weighing on export will also mean that the return to a current account surplus seen last year (at almost 2% of GDP) may not improve any further this year or next. This is also a headwind to GDP growth.

Figure 1: Unprecedented Divergence Between Goods and Services Output

Source: Eurostat, Euro billion

Amid what has been a disinflation process so far very much supply driven, it is very difficult to assess the likely full damage to demand from current tight financial conditions let alone the extent to which depleted spending power may rein in pricing power. But encompassing what has already been a marked softening underlying inflation, we still envisage headline HICP moving below 2% more durably next year (after a brief decline below 2% in the short-term) with the core not far behind. This 2024 picture is a little higher than envisaged in the June Outlook, partly due to some fiscal measures and energy price rises and service price resilience. The latter has served to heighten worries about price persistence and the so-called ‘Last Mile’ problem. But such concerns gloss over the fact that core goods prices have undergone the opposite trend, this divergence enough to mean that overall HICP inflation has been averaging below 0.2% m/m in adjusted terms in the last few months. In addition, the omens from wages point to services inflation slowing in due course.

Fiscally, policy is projected to tighten significantly though this year, mainly due to the withdrawal of a large part of the energy support measures. A further but more modest tightening of the fiscal stance may occur for 2025-26, on the back of the scaling down of the remaining energy support, slower growth in subsidies and other fiscal transfers, and some measures on the revenue side. The tightening this year may be less than we envisaged three months ago on account of what still look to be spending overshoots in some countries, but these are likely to be reversed implying a likely relatively tighter fiscal stance in 2025. Thus, the headline EZ budget gap may fall to around 3.3% of GDP this year from 3.6% last year (0.3 ppt higher than thought three months ago) but will not any drop further into 2025 without more consolidation measures which do seem to be under active consideration, possibly pressured by new EU fiscal rules. Thus, with headline budget gaps that may stay around 3% of GDP this year and next, the fall in the EZ government debt ratio to 88.5% of GDP last year will likely be followed by a rise.

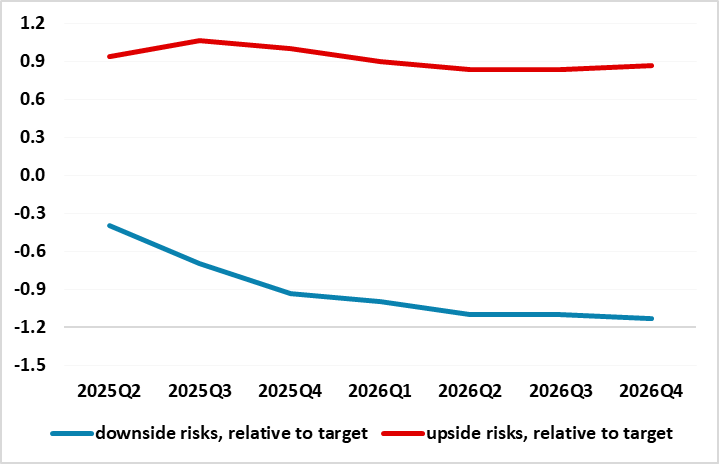

Figure 2: ECB HICP Projections Suggest Growing and More Sizeable Downside Risk

Source: ECB Sep Marco Economic Forecasts, aggregation of the 30%, 60% and 90% probabilities that the outcome of HICP inflation will depart from target. For more information, see Box 6 of the March 2023 ECB staff projections

ECB: Real Economy Issues on Par with Inflation?

That the ECB cut the discount rate again this month and again by another 25 bp (to 3.5%) was no surprise. Neither was an unchanged tone at the press conference, with no clearer acknowledgment of downside risks even given ECB GDP projections which were much more pessimistic than headlines suggest. In turn, this helped reinforce the ECB view that HICP inflation would move below 2% in 2025 and stay there and where details in updated forecast do show that there are downside risks to the ECB’s HICP outlook (increasingly) exceed those to the upside (Figure 2). Equally unsurprising, there was nothing like any firm pointer to the speed and/or timing of further moves. But as these projections are based on market rate thinking which envisages the discount rate close to 2% into 2026, it thereby endorses such thinking too. Moreover, given the stimulus that the circa-40 bp drop in market rates should have brought to the economic outlook projections, the downward revision the GDP outlook is notable.

Even so, our long-standing view that the ECB may cut only a further 25 bp this year remains but where more weak survey data would warrant a move as soon as October. Regardless, we still think that by year-end more durable evidence of labour costs easing should convince the ECB to continue easing and we see 100 bp further easing through 2025 (still quarterly), with the deposit rate then nearing 2% and thus more in line with a perceived neutral setting but hardly moving into anything like a clear expansionary stance. This may be a little slower than current (more frenzied) market thinking but we are unwilling to follow this until we see more supportive evidence. What we think though is, that amid these downside growth risks, alongside a target-consistent medium-term inflation outlook will make the ECB more attentive to real economy numbers. This may already be occurring. We have for some time suggested that alongside our below-consensus economic projections the policy outlook risk is also to the downside, but more in terms of faster rate cuts that larger ones – the latter would take a fresh recession which we have as a 10% risk.

Germany: Unwilling or Unable to Reform?

We have highlighted repeatedly the structural factors increasingly affecting the economy, do a degree to stress that Germany’s economic malaise is far from purely a cyclical development. All of which helps explain why the German economy is likely to remain weak into 2025 and probably beyond and why Germany is at the forefront of the Draghi Report. The Report has not had a clearly positive reception in Germany. Especially from the more right of center political thinking the worry is about the added EU debt that the Report recommends and a concern that Germany will have to foot the bill for any new EU industrial strategy. The misgivings also encompass an unwillingness to let go of Germany’s recent economic heritage, built on export-driven growth, with a skilled workforce, strong innovation system and efficient infrastructure underpinning superior manufacturing. But the economic backdrop has changed to a degree where Germany needs to do so also just to catch up. Indeed, the Federation of German Industries estimates that Germany needs to invest EUR 1.4 tn by 2030 to bolster its ever-creaking industrial base and stay competitive in the global market.

Another reason for some complacency is that Germany’s labour market overall is still adding jobs - employment has risen to a record-high of more than 46 mn. But the compositional change is the snag as better paid manufacturing jobs are vanishing perhaps even more rapidly as the likes of Volkswagen consider earlier and compulsory redundancies. The result has been a jobs market increasingly reliant on poorer paid service employment, leading to weak(er) income growth, rising inequality and higher public spending.

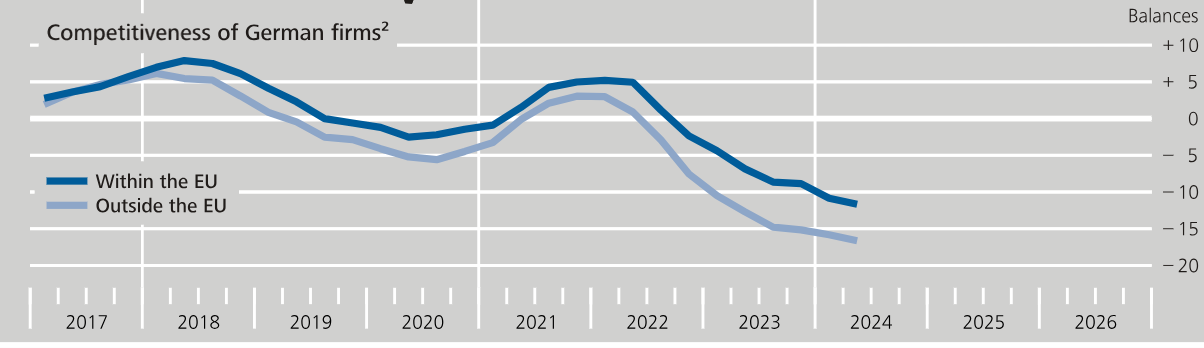

Indeed, while Germany may have re-entered mild recession, the pertinent question is still whether the soft growth numbers we anticipate into 2025 will feel much different. Domestic demand is set to pick up but only slowly into 2025, as real wage growth returns. However, investment growth is projected to remain well below pre-pandemic levels, constrained by still-high financing costs and uncertainty. Exports will remain sluggish in 2024 and only slowly recover in 2025 as competitiveness becomes an ever-clearer headwind (Figure 3) and any rise will be offset by recovering imports. Even so, the current account surplus may be over 6% of GDP this year and next. Regardless, we have downgraded our 2024 GDP picture by a notch compared to three months ago to zero and twice that to 0.7% for 2025, both well below consensus. Notably, the scale and particularly the durability of the weakness is evident from the fact that we still do not see the recent peak in the level of GDP (ie Q3 2022) being re-attained until mid-2025 as there are downside risks as for all the structural problems Germany faces, cyclical policy is biting too, both monetary and fiscal.

Partly reflecting what is still an output gap likely to remain negative into 2025, inflation is falling broadly and we see it down more durably below 2% in 2025. Even so, consumer spending is likely growing very slowly on average in 2024, not even repairing the 0.4% fall seen through 2023 as the near 10% current fall in house prices both erodes household wealth and puts added upward pressure on rents. All of which means that domestic demand weakness is likely to see the biggest damage emanating from the still-slumping construction sector. Indeed, building activity is falling increasingly and broadly, albeit led lower by residential construction work, and where surveys very much suggest that difficult conditions will persist for at least the coming year.

Figure 3: German Competitiveness Still Dropping and Broadly So

Source: Bundesbank, % balance based on question assessing company’s competitiveness position chg over 3 mths

Regardless, the fiscal picture remains in a state of flux amid continued speculation about the debt brake. Admittedly, the budget deficit is likely to fall again this year from around 2.5% of GDP in 2023 towards 1.5% and lower still in 2025 as a result of the phase-out of measures to mitigate the impact of high energy prices dropping from 1.2% of GDP in 2023 to 0.1% of GDP in 2024. In addition, solid tax revenue and strongly increasing social contributions, due to rising salaries and social contribution rates will continue into 2025. However, projected initiatives on climate policy and defense are rising sharply as have debt interest costs, all accentuating economic uncertainties.

France: Fiscal and Political Impasse

France’s politics are deadlocked and the result is a fiscal and probably an economic impasse that may add to existing headwinds. After much delay, a new prime minister has been appointed in the form of an alleged independent Michel Barnier. But his appointment has angered the left, kept the center neutered, leaving the right key in determining whether a new government can even be formed, let alone sustained without anything like a working parliamentary majority. Highly divisive demands are likely to put forward, not least the right-wing National Rally eyeing contentious reforms to France’s two-round legislative elections in favor of a one-round system of proportional representation in the hope of winning the 2027 presidential election. All this is adding to economic and fiscal policy uncertainty amid ever clearer signs of a budget deficit overshoot that may be much larger than the 5.5% of GDP 2023 fiscal gap. Indeed, even the planned a further 16 bn in savings promised this year by the last administration may not get the deficit back on track to the existing 5.1% of GDP budget goal (up from an initial 4.4%). Having already been put into a so-called excessive deficit procedure, France has asked the EU for more time to submit revised debt and deficit reduction plans but its own laws necessitate that a budget for next year needs to be outlined by October.

As a result, with little chance of passing difficult structural and fiscal reforms, already-growing debt sustainability questions look even worse as the debt ratio looks set to rise by over one ppt per year from the 110% set in 2023 and only partly due to higher debt servicing costs; the pass-through of higher borrowing costs will be gradual because the French government's debt is long dated, with the average maturity longer than 8.5 years.

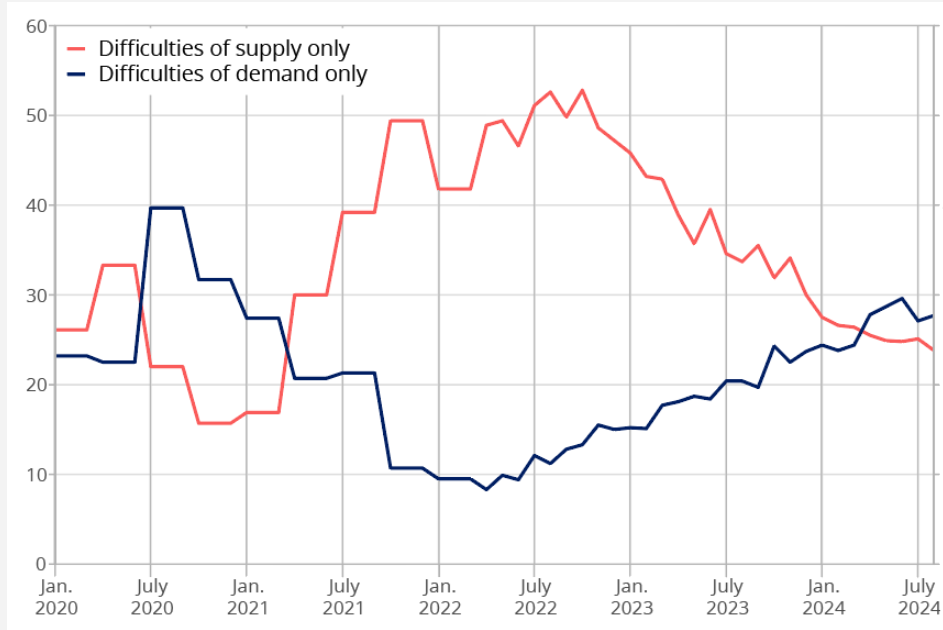

Indeed, encompassing a persistent structural gap, budget deficits may average around 5% of GDP out to 2026, with the risks that real economy fall-out creates a vicious circle due to the need to make ever larger fiscal consolidation measures to suppress growing market jitters. This is all the more notable as government spending has actually been a tailwind for France’s GDP back drop in the last year. The now emerging headwinds have actually not prevented an upgrade to this year’s forecast to 1.1% from 0.9% but solely due to the better than expected government spending and weak import driven Q2 outcome – the recent Olympics may cause a positive blip this quarter but one largely reversed in Q4! Even so, we see a gradual recovery next year, but still a weak one not least given the still soft (ie below-par) messages from the various business surveys which suggest and an increasing impact from weak demand (Figure 4). We now see a 2025 growth picture of 1.0%, 0.2 ppt lower than forecast three months ago. But this comes with downside risks, not only from the budget cuts, but also the lagged impact of the rise in interest rates and the economic and possibly more persistent political uncertainty. Notably, private consumption will be weak as those energy support measures are fully reversed into 2025 and as high savings remain locked up in illiquid assets. So the boost will be modest and consumer spending will grow no more in 2024 than overall GDP, this also the case for 2025. Investment is projected to recover progressively into 2025 but only after fresh drops in coming quarters. Meanwhile, over the forecast horizon, net exports are set to have a minimal and possibly negative contribution to growth. Exports growth, which traditionally relies on a few specialized sectors such as aeronautics and other transport equipment, is expected to be offset by rising imports mirroring the recovery of household consumption. Hence, a still clear current account deficit will persist into next year, albeit staying under 1% of GDP. But France still faces pressure in terms of its competitiveness, judging by its persistent trade deficit.

However, this soft growth outlook will reinforce the broad disinflation already very much evident. Thus we still envisage CPI inflation at 1.8% next year even though there is some upward revision to that for this year (to 2.4%). This is backed up by business surveys very much suggesting that expected price cost pressures are back to pre-pandemic levels generally. All of which, however, reflects the growing impact of the marked recent damage to spending power alongside tight(er) financial conditions. These are which are likely to lead to a further reining in pricing power and a rise in the unemployment rate back above 7.5% into 2024 and through 2025 and where companies are likely to see profit margins fall further.

Figure 4: France Industry Worries – Demand Taking Over From Supply

Source: INSEE, supply and demand difficulties in industry, % balances

Italy: Fiscal Elephant Still Round the Corner

As was the case three months ago, fiscal worries seem contained, at least that is the message from the 5-10 bp fall in sovereign spreads vs Germany at a 10-year horizon compared to the last Outlook. Notably though, recent actual budget data are hardly reassuring with no improvement in the first half the year as far as deficits are concern. The question is how and when fiscal policy is reined in as the government attempts to unwind the so-called Superbonus scheme (a generous tax incentive for housing renovation, which should be entirely phased out by next year). As we have stressed before, its impact has been marked in two crucial ways. It has boosted GDP growth but it has also damaged the fiscal situation. Its removal will help, but we still see budget deficits of just under 5% of GDP persisting this year and next, with upside risks not least given a structural gap of over 5%.

Thus, we still feel the current sovereign spread is too low not least given the still unfavorable debt dynamics Italy faces in coming years. Indeed, Italy needs to start running a primary budget surplus: Finance Ministry figures suggests this will occur from next year. But we are doubtful, something that the European Commission also are wary about given that Italy also faces an excessive deficit procedure on the basis of an expected five-point rise in the debt ratio to 142% if GDP over this and next year – and that on the basis of a budget gap just over 4% (which to us seems too optimistic). Nonetheless, this is something that seems discounted by markets, they partly reassured by what seems to be an Italian government not willing entirely to dispense with fiscal consolidation.

But the economy has shown some resilience, but we have still made a modest (0.1 ppt) downgrade to 0.7% GDP growth for both this and next year. Moreover, the growth picture still has some downside risks, the latter mitigated somewhat of late by what are slightly less negative business surveys.

Thus the real activity picture is both a reflection of and a cause of the increasingly soft inflation backdrop and outlook. Regardless, the soft inflation picture is not likely to foster much recovery in what has recently been falling real disposable incomes. The very gradual increase in nominal wages (contractual hourly earnings rising by around 2.5% next year), together with less positive employment conditions, will keep private consumption growing by less than GDP into 2024, with activity undermined further by the planned expiry of all temporary income-support measures. Capital spending may pick up only moderately in 2024, as the fall in housing construction is offset by Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF)-supported increases in investment in infrastructure and equipment. Net exports may provide a little support to growth in 2024, but where the return to a current account surplus seen last year may be built upon into 2025 at over 1% of GDP.

Spain: Services Soldier On

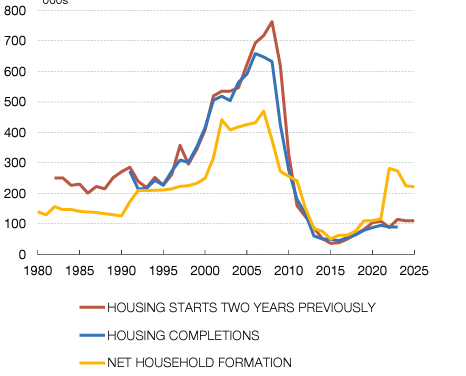

At the top end of the EZ growth divergence is Spain. As suggested above, the EZ more recently has been driven solely by services and it is the fact that Spain’s economy has a much larger share of services in its make-up compared to the EZ average (75% vs 70%) has helped the country to out-perform. More notably, and unlike the EZ as a whole, there is little in survey data to suggest that services strength is ebbing, boosted by a tourist backdrop which has seen a 10% y/y rise in international visitors and where this may account for a quarter of the 2.6% GDP growth rate we now expect for this year (not surprising as tourism accounts for 13% of Spain’s GDP). Given this solid backdrop, it is notable that this GDP projection is actually a notch higher than we envisaged three months ago, partly a reflection of the strong Q2 outcome. Other sectors are also buttressing growth, with renewable energy now accounting for half of Spain’s electricity usage. There is also the construction sector where current strength is likely to persist given what seems to be a growing imbalance between housing demand and supply (Figure 5). But at the heart of this is a robust labor backdrop which has seen a marked rise in the Spanish workforce (largely a reflection of returning emigration) enough to have effectively increased the economy’s potential growth rate. But that workforce rise has started to reverse and that this may continue Regardless, the unemployment rate may continue to fall, although its reduction will be moderate from 12.1% in 2023 to 11.8% in 2024 and to 11.6% in 2025.

But slower workforce growth will curb housing demand and that explains the underlying reason we envisage growth slowing into 2025, albeit to an upgraded but below-consensus 1.7%. This slowing also reflects what we think will be a tourist sector that may have peaked where demand may be held back by high prices, over-crowding and the growing resistance from locals (involving protests) about the spill-overs from what some locals consider are excessive overseas visitors. There is also the soft EZ backdrop that we envisage from which Spain will not be immune entirely. Regardless, consumer demand is expected to continue lagging overall growth, and where export strength may also ebb - this largely a result of tourism possibly peaking. Thus we see a largely unchanged current account balance of just over 2% of GDP both this year and through 2025.

Figure 5: A Growing Housing Imbalance?

Source: Bank of Spain, 000s

On the inflation side, we expect the underlying trend to be one of more modest moderation. Indeed, we see inflation slowing to an average of 3.0% this year (an upgrade due energy prices, fiscal measure reversals and high hotel prices) but with the projection of 2.0% for 2025 intact. This reflects some slowing in terms of services inflation, reflecting a limited impact of the so-called second-round effects.

Spanish PM Pedro Sánchez has managed to maintain a minority coalition administration amid ever clearer political divides. However, amid the need to pander to minority parties asks whether this may have a fiscal cost as Sanchez is likely to have to buy support, this having budget consequences. But the strong economy has helped push revenue growth above that of government spending, meaning that the budget gap may be pulled back to just over 3% of GDP this year (from 3.6% in 2023). But this may be short-lived with the gap opening afresh next year and this is one reason why Spain has also seen the EU put it under an excessive deficit procedure despite