This week's five highlights

India, Pakistan, and the New Escalation Paradigm

Tariff Man Posing for Another Strike

FOMC leaves rates unchanged, sees increased risk on both sides of mandate

BoE Divided by Scenarios

Norges Bank Policy Easing Continues to be Deferred

Riksbank Fresh Easing Hints Confirmed

India and Pakistan are now embroiled in their most serious military confrontation in years, with hostilities expanding across air, land, and unmanned domains. Following the May 7 cross-border strikes under Operation Sindoor, India launched a calibrated military offensive on Thursday targeting Pakistani air defence radars in Lahore. The move came after Pakistan attempted coordinated drone and missile attacks on six Indian military bases — an act New Delhi described as a significant escalation warranting a “domain- and scale-matched” response. India maintains that its posture remains retaliatory and proportionate. But the reality is clear: both sides are now operating at higher rungs of the escalation ladder — with little buffer between crisis management and open conflict.

Tensions between India and Pakistan have reached their highest point since the 2019 Balakot airstrikes, with the unfolding crisis now entering a volatile and dangerous phase. What began as a measured Indian response to the April 22 Pahalgam terror attack has since evolved into a broad-spectrum confrontation involving precision airstrikes, drone warfare, missile exchanges, and sustained cross-border artillery fire. As Operation Sindoor enters its second week, the space between deterrence and escalation is narrowing rapidly, testing the strategic thresholds of both nuclear-armed states.

Perhaps the most alarming development is the compression of the escalation ladder. In past crises, action and reaction were spaced over days or weeks, allowing for signalling, backchannel diplomacy, and international mediation. In this crisis, the timeline has collapsed: drone attacks are launched, intercepted, and retaliated against within hours. The strategic danger lies in miscalculation. With both militaries operating on high alert, even a limited tactical error could trigger a disproportionate strategic response. The erosion of time and space for crisis management is now the central risk factor.

India has briefed key allies including the US, UK, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, framing its actions as defensive and proportionate. But with global attention divided, international actors have so far refrained from formal mediation. China has aligned more closely with Pakistan’s narrative, calling for a "neutral investigation."

Figure: U.S. Reciprocal Tariffs and Goods Exported to U.S./GDP (% and USD Blns)

| US universal and reciprocal tariffs | Goods exports to U.S./GDP (2024) | US Imports in Goods | |

| China | 34% | 3% | 439 |

| European Union | 20% | 4% | 606 |

| Japan | 24% | 2% | 148 |

| Vietnam | 46% | 29% | 137 |

| South Korea | 25% | 8% | 132 |

| Taiwan | 32% | 15% | 116 |

| India | 26% | 3% | 87 |

| United Kingdom | 10% | 3% | 68 |

| Singapore | 10% | 8% | 42 |

| Brazil | 10% | 2% | 42 |

| Mexico | 0% | 23% | 334 |

| Canada | 0% | 19% | 412 |

With the U.S. equity market having rebounded, President Donald Trump instinct on tariffs have seen threats of pharma tariffs and a 100% tariff on non U.S. films. Slow progress is also reported on bilateral deals, despite White House PR spin. However, Trump will see pressure rising from three sources in May-July from a stagflation hit, weaker voter approval and a renewed downturn in the U.S. equity market. This will put pressure on Trump to deliver trade deal by the July deadline; try to get a trade truce with China (here) and curb further tariffs.

Trump indicated that he will likely announce tariff rates of pharmaceuticals in two weeks showing that he is committed to his tariff agenda to raise tax revenue/shift production back to the U.S. as well as getting better trade deals. A 25% rate has previously been mentioned by Trump, but the hints are that the implementation will be delayed to allow companies to shift production back to the U.S. and avoid a shortage of pharmaceuticals in the U.S. It is also not clear whether the pharmaceutical tariff will be across the board or only certain drugs/ingredients. All of this is classic Trump that wants to go on the offensive with tariffs now that the U.S. equity market has seen a rebound. Additionally, Trump is threatening a 100% tariff on non U.S. films, though details on this remain unclear.

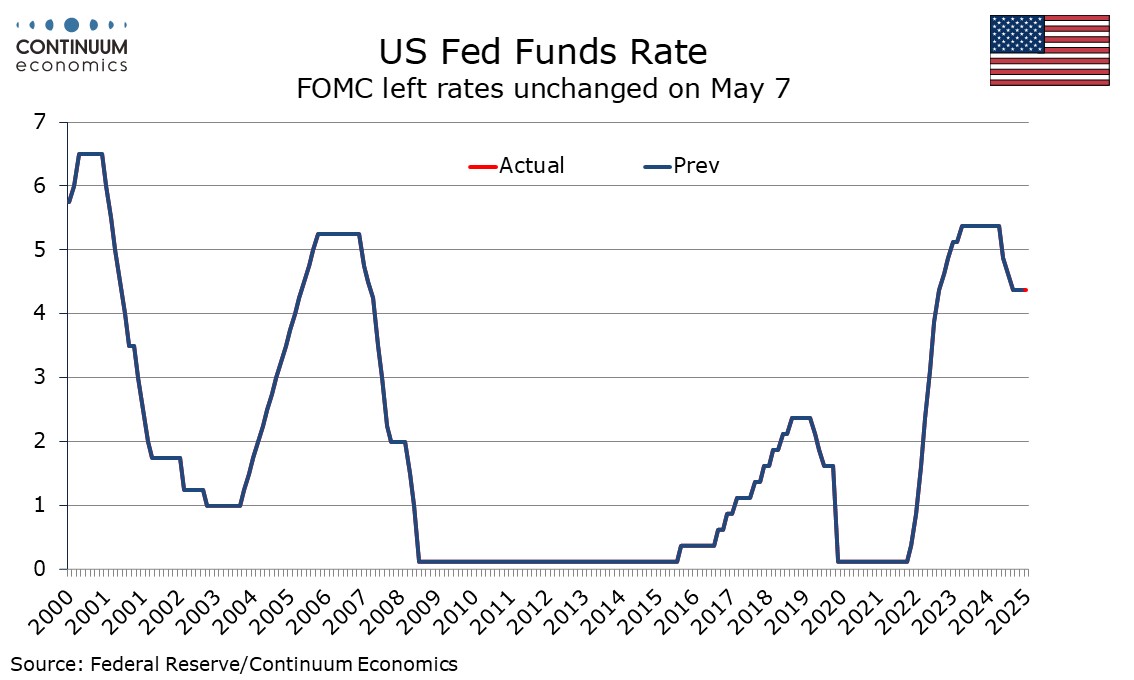

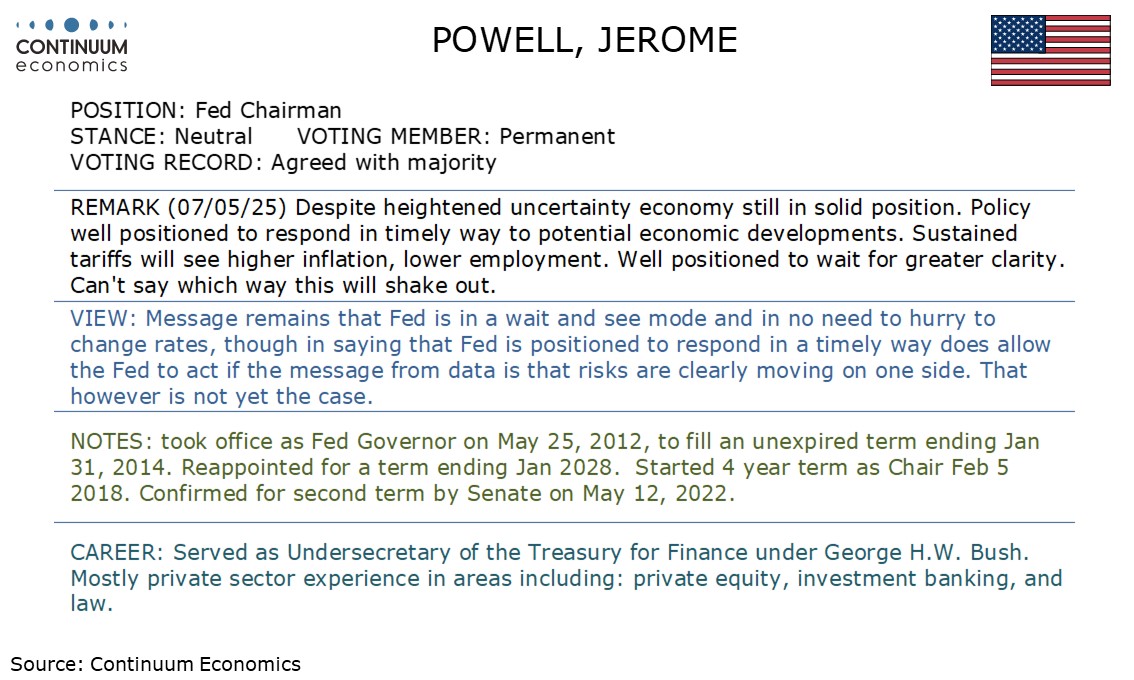

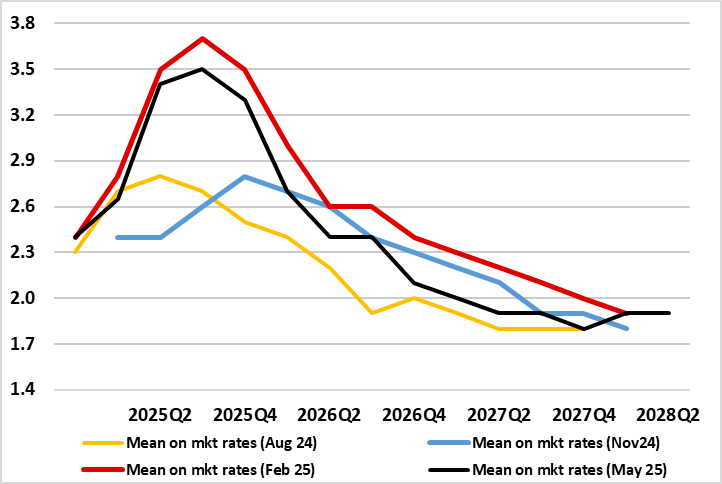

The FOMC has left rates unchanged at 4.25-4.5% as expected. The main change in the statement is to note that the risks of higher unemployment and higher inflation have both risen, which gives little insight on any policy bias though suggests that the Fed could be responsive to data going forward. The assessment of the economy has not changed much from the last statement on March 19, repeating that recent indicators suggest economic activity has continued to expand at a solid pace, with the opening caveat that swings in net exports have affected the data both acknowledging and downplaying the fact Q1 GDP marginally declined. The views on unemployment, stabilized at a low level, and inflation, somewhat elevated, are unchanged.

Uncertainty is seen as having increased further and risks on both sides have increased. Wording on quantitative tightening has changed but only because a change in policy was announced on March 19. No changes were announced in this statement. There were no dissenting votes at this meeting.

Figure: BoE Upgraded Inflation Outlook Still Too Gloomy!

The widely expected 25 bp Bank Rate cut (to a 2-year low of 4.25%) came amid a less dovish rather than a more hawkish assessment than was envisaged beforehand. While the new Monetary Policy Report MPR) now sees inflation fall below target almost a year earlier than seen three months ago (Figure), this largely reflects weaker energy price assumptions alongside only a modestly larger negative output gap. Instead, a friendlier interest rate picture helps limit any damage to the GDP outlook, this in turn meaning that the envisaged drop in inflation while earlier, does not intensify further out. But that growth outlook has a clear downside risk tilt, partly reflecting the uncertainty aspect from the U.S. tariff threat. We still think the BoE is too optimistic regarding the growth outlook and not encompassing the ensuing disinflation risks. As a result, we continue to point to at least two more 25 bp cuts this year and probably three, with a full ppt on the cards for 2026, that still leaving the policy stance slightly restrictive.

It remains clear that MPC divisions remain given the three-way manner in which this vote materialized. Such divisions have been enough for the BoE to have altered its rhetoric as far back as February to stress the need for policy to be framed carefully as well as gradually. This line f thinking continued to be the case this month, also repeating that monetary policy will need to continue to remain restrictive for sufficiently long. The fact that two MPC members voted for no cut at all this time around is possibly not as hawkish as it appears, not least as their rationale was partly based around what we think is flimsy evidence of a still tight labor market. But it is clear that the BoE overall is placing much more emphasis on a possibly weaker supply side of the economy (both at home and globally) than perhaps markets are, this explaining the lack of a clearer disinflationary outlook.

Indeed, while the MPR stressed there were growing risks from potential global trade arrangements depending on how trade policies unfolded, it alleges risks lie on both sides. As a result, the BoE contend that UK inflation could be affected by a wide range of factors such as shifts in trade patterns, supply chain disruptions in the UK and abroad, and movements in global exchange rates. On the one hand this meant that it was possible that the ultimate net effect of these developments could be materially more disinflationary for the UK than in the baseline forecast, but it was also possible that the effect could be slightly inflationary in the longer term due to supply factors. Overall, while it is too early to conclude over what period and to what degree different economic effects could materialise we think the disinflation alternative is both more likely and the more sizeable.

Figure: Weak Krone Not to Blame for Inflation Spike

It was hardly a surprise that the Norges Bank again kept policy on hold when it gave its latest verdict as was the fact that it failed to be any more explicit about when the rate cut cycle may begin. Instead, while still suggesting rate cuts later this year, it cautions about premature easing. This is somewhat hindsight forecasting given that until the stable policy decision six weeks ago it had been flagging very clearly a rate cut by March. As a result, it has kept the policy rate at 4.5% on the back of inflation in recent months having been markedly higher than expected. But it did note that recent global trade tensions complicate the policy outlook, both by adding to downside risks for both growth but also adding to downward pressure on the krone.

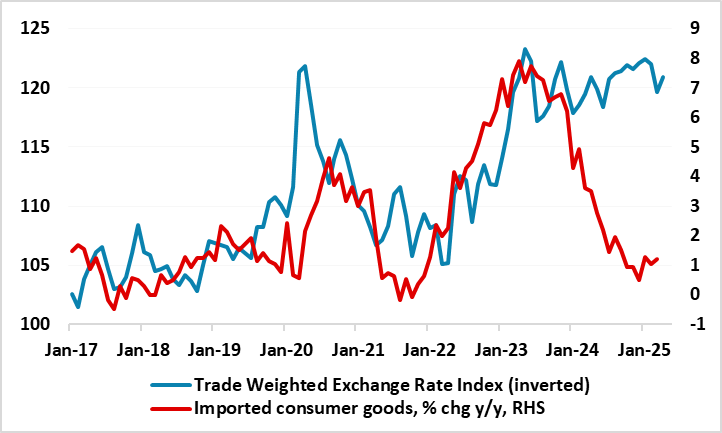

The Board does acknowledge that with trade barriers having become more extensive, there is uncertainty about future trade policies. But somewhat puzzlingly, it suggests this could pull Norway’s interest rate outlook in different directions. On the one hand, the global growth outlook appears to be weaker, and oil prices have fallen. Norway’s main trading partners are now expected to make more rate cuts than previously. On the other hand, the krone has weakened somewhat and been weaker than assumed.

Once again, the (weak) krone is at the centre of Norges Bank thinking. This currency preoccupation of the Board seems very puzzling to us as a) this hawkish policy leaning has failed to bolster the currency and b) the weak currency has not prevented a marked fall in inflation encompassing much reduced imported price pressures, at least prior to November numbers. Regardless, currency weakness has not prevented imported consumer goods inflation from falling and the latter (at around 1% y/y) is hardly responsible for the current CPI overshoot (Figure 1). As a result, it is worth underscoring that, since the last hike 15 months ago, a hawkish tone of keeping rates high for some time has repeatedly failed to unwind krone weakness, this despite the added bonus of a substantial Norwegian current account surplus. But perhaps bad habits are hard to break.

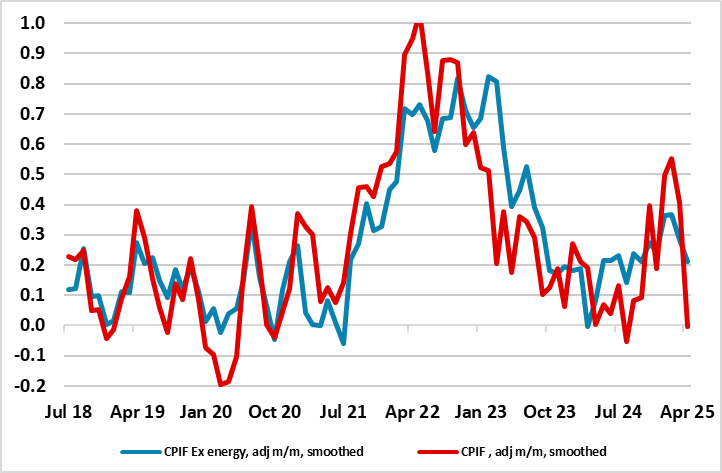

Figure: Inflation Scare Reverses

The very much expected stable policy decision at this Riksbank verdict was the second in succession but where the Board veered away from its previous assertion that that, with the policy rate now at 2.25%, this may be the end of the easing path. Instead, and amid the stronger currency and softer CPI figures, and with weaker real activity signs, it was a little more open about the possibility of additional rate cuts. While underscoring that monetary policy is currently well-balanced and that it is wise to await further information to obtain a clearer picture of the outlook, the Riksbank did note that that it is somewhat more probable that inflation will be lower than that it will be higher than envisaged in its March forecast. From the Riksbank perspective, this could suggest a slight easing of monetary policy going forward.

As no new forecasts were due until the June 18 Board verdict, the Riksbank did resort to rhetoric to hint at a revised policy outlook without recourse to formal projections. We still see a further rate cut albeit maybe not as soon in June and also suggest that the risks of further moves both as the recent inflation scare recedes and the Riksbank takes note of the likely further rate cuts we think is in the offing from the ECB. In this regard the effective exchange rate has appreciated to a five-year high and to almost what was envisaged by the Riksbank into 2026.