This week's five highlights

China and UK Precedents for Trump Tariffs

U.S./China Trade Truce Reduce Downside and Extra Stimulus Prospects

India Redraws the Rules

U.S. April CPI Shows Little tariff pass-through so far

UK Q1 GDP Jumps But Erratic and Overstating Activity

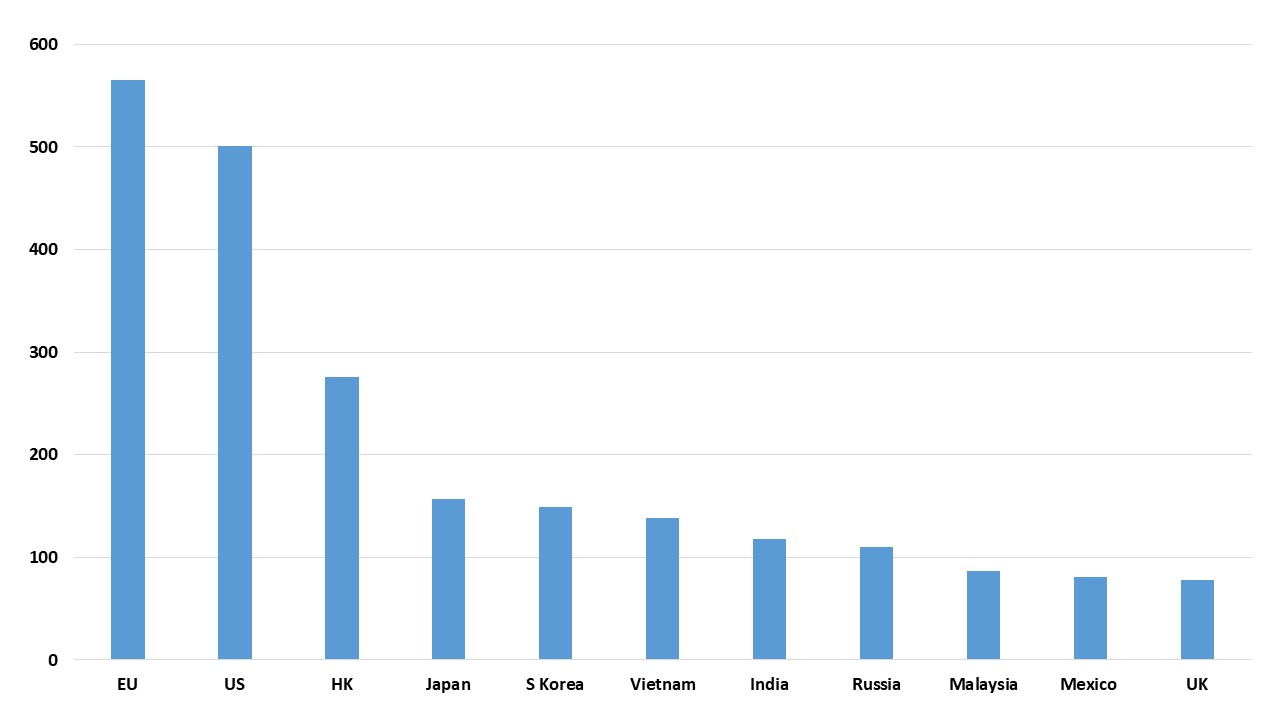

Figure: U.S. Reciprocal Tariffs and Goods Exported to U.S./GDP (% and USD Blns)

| US universal and reciprocal tariffs | Goods exports to U.S./GDP (2024) | US Imports in Goods | |

| China | 34% | 3% | 439 |

| European Union | 20% | 4% | 606 |

| Japan | 24% | 2% | 148 |

| Vietnam | 46% | 29% | 137 |

| South Korea | 25% | 8% | 132 |

| Taiwan | 32% | 15% | 116 |

| India | 26% | 3% | 87 |

| United Kingdom | 10% | 3% | 68 |

| Singapore | 10% | 8% | 42 |

| Brazil | 10% | 2% | 42 |

| Mexico | 0% | 23% | 334 |

| Canada | 0% | 19% | 412 |

Source: BEA/Continuum Economics

The U.S./China have announced major reductions in reciprocal tariffs to 10% with other measures postponed for 90 days. Though the U.S. is still imposing an extra 20% due to fentanyl, China will likely make some moves that could also help to reduce this. This is in line with our previous thinking and is good news, as it dials the temperature down on the trade wars. However, a U.S./China trade deal will take 6-9 months due to major differences over reducing the bilateral trade deficit. Meanwhile, the U.S./UK trade framework shows that 10% is the likely minimum reciprocal rate and other countries may not get as favorable product exemptions as the UK.

Reciprocal tariffs have been reduced to 10% for China and the U.S. effective this week after the Geneva meeting, with the extra amounts postponed for 90 days. In reality the penal extra reciprocal rates are unlikely to return, but is just a negotiating tactic now and extra reciprocal tariffs are unlikely to be imposed if trade negotiations are carrying on between China and the U.S. Though the U.S. is still imposing an extra 20% due to fentanyl, China will likely make some moves that could also help to reduce this. The fact that it was not reduced now is likely for Trump to posture to U.S. voters. This is in line with our previous thinking and is good news, as it dials the temperature down on the trade wars. Firstly, the trade freeze with China will now likely ebb. With inventories already in the U.S., this could mean that the hit to supply chains is temporary. Additionally, the price hikes in the U.S. will now likely be scaled back meaning less of a hit to demand and the U.S. economy – this also lower the risk of a U.S. recession. However, a U.S./China trade deal will take 6-9 months due to major differences over reducing the bilateral trade deficit. Greer noted that the U.S. still wants China to commit to buying more imports from the U.S. to reduce the bilateral trade deficit. Additionally, with the reduction in the effective rate and reducing immediate domestic U.S. political pressure, this will likely make the U.S. willing to push hard in the real negotiations. The effective reciprocal rate in an eventual deal could be higher than 10%, though with the fentanyl number going to 10% or zero.

Figure : China Exports by Country 2023 (USD Blns)

The alternative hard landing scenario in China has been reduced significantly with the trade truce with the U.S. However, China will still have to cope with a minimum 30% overall tariff, with only around a 10% reduction in the fentanyl tariff likely to be agreed in the coming months. Our baseline for an overall trade agreement is Q4 2025 for Q1 2026 implementation and this prolongs the impact of moderately high tariff rates in 2025. Extra fiscal policy expansion will also be less and we stick with a 4.2% 2025 GDP growth forecast.

For now we keep the 4.2% GDP forecast for 2025 for a number of reasons.

• April trade freeze and ongoing tariff effects. The April surge in reciprocal tariffs by the U.S. will likely hurt Q2 GDP numbers, with anecdotal evidence suggesting almost a freeze is some U.S. exports. While some export diversions could have occurred to other main trading partners (Figure 1), this is likely to have been modest. The May 12 relief will help exports to the U.S. recover, but at a minimum 30% tariff for most goods. This remaining tariff will slow export growth to the U.S.

• Prolonged trade negotiations before deal. While we do see scope for a 10% reduction in the fentanyl rate, the Trump administration is very keen for political and strategic reasons to impose 25% on pharmaceuticals on all countries and this should be seen in the coming weeks. A trade deal could reduce the reciprocal/fentanyl tariff to 15-20%, but would require concessions from China that will likely take 3-9 months to agree. The 90 day deadline will likely be delayed by a further 90 days in August. China could easily buy more oil/LNG/chemicals and soybeans from the U.S. provided they do not become too dependent on the U.S. However, the U.S. earlier this year wanted a phase 2 trade deal with penalties if import or trade deficit reduction targets were not meet. This could lead to disputes in the coming months and prolonged negotiations. Our baseline is agreement Q4 2025 for Q1 2026 implementation and this prolongs the impact of moderately high tariff rates in 2025. Trade policy uncertainty will also impact China business investment as well.

• Fiscal easing in 2025 has been below expectations at around Yuan2.5trn. Part of the reason is that the authorities feel constrained by the wider surge in government debt (Figure 2) than the official figures show. China authorities also constantly worry about the total government/corporate and household/GDP that has surged since 2007 to over 300% and above the U.S. and EZ. With the hard landing scenario reduced, this likely now means only an additional Yuan1trn extra fiscal expansion later this year rather than Yuan2trn. Official rates and RRR could also be cut more slower in H2 2025.

After ten days of rapid military escalation, India and Pakistan agreed to a ceasefire following one of the most intense cross-border confrontations since 1999. The agreement, which came into effect after backchannel outreach from Pakistan’s Director General of Military Operations (DGMO), halts for now a spiraling cycle of drone warfare, missile strikes, and artillery fire. Yet beneath the appearance of de-escalation lies a recalibrated Indian doctrine, one that marks a significant departure from past restraint.

The conflict erupted following the April 22 terror attack in Pahalgam, which killed 26 civilians and was claimed—then denied—by The Resistance Front, a Lashkar-e-Taiba proxy. In response, India launched Operation Sindoor on the night of May 6–7, a tri-service precision operation targeting nine terrorist training camps in Pakistan and Pakistan-occupied Jammu and Kashmir (PoJK). Notably, the operation was designed to avoid military and civilian infrastructure, reinforcing India’s narrative of a non-escalatory, pre-emptive strike.

However, Pakistan responded with drone swarms and missile launches on Indian military bases across multiple states. India’s air defence grid neutralised these attacks, but Pakistani artillery barrages led to civilian casualties. In response, India escalated further by targeting Pakistani air defence systems in Lahore, Sargodha, air bases in Nur Khan, Murid, Rafiqui, and reportedly near strategic locations including Rawalpindi. Some reports even indicate that sites proximate to Pakistan's suspected nuclear command infrastructure may have been deliberately skirted—yet brought within targeting range, as a calibrated signal.

The current ceasefire may hold in the short term, but it does not signal resolution. India’s military posture has changed from reactive to pre-emptive, and this recalibration is here to stay. While New Delhi has signalled restraint by accepting the ceasefire, it has drawn a hard line: terrorism will be met with force, not diplomacy. There are meetings scheduled between the DGMOs and further details are awaited.

For Pakistan, the outlook is more precarious. The Munir doctrine—framing Kashmir as existential and invoking religious nationalism—has failed to alter the strategic environment. International sympathy has shifted; global media and diplomatic circles broadly endorsed India’s narrative of pre-emptive self-defence. Pakistan’s economy, already fragile, has come under further strain from market losses and airspace shutdowns.

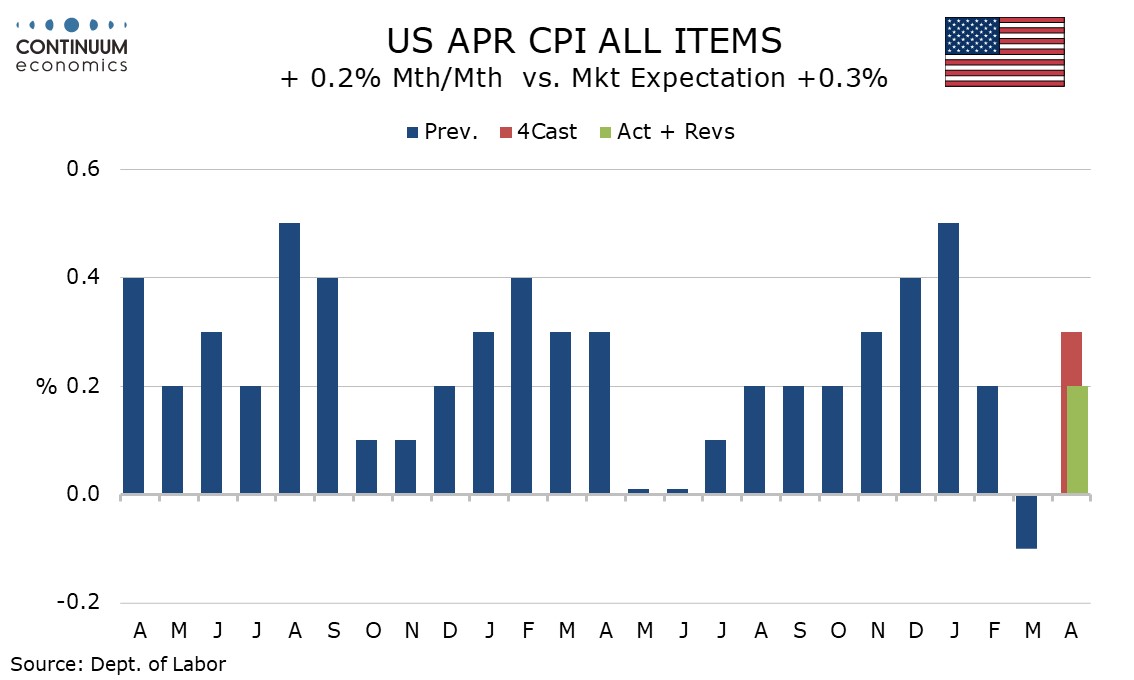

April CPI is on the low side of expectations at 0.2% both overall and ex food and energy, showing a loss of inflationary momentum since a strong start to the year in January, despite the imposition of tariffs. The core rate was up 0.24% before rounding, with the overall pace 0.22%, so the surprise is modest.

Commodities less food and energy, where tariff risk was seen as strongest, rose by only 0.1%, with used autos down by 0.5%, a second straight decline, and apparel, much of which is imported, down by 0.2%. Energy commodities fell by 0.2% with gasoline down by 0.1% but energy services were firm with a 1.5% increase to leave energy up 0.7% overall. Food fell by 0.1% as eggs plunged by 12.7% in a correction from recent sharp gains. Eggs are still up 49.3% yr/yr. Services less energy returned to trend at 0.3% after a weak 0.1% increase in March. Air fares remain weak with a 2.8% decline reflecting reduced demand to visit the USA, but transport services rose by 0.1% after a 1.4% March decline with the air fares drop less steep than March and auto insurance correcting a March decline.

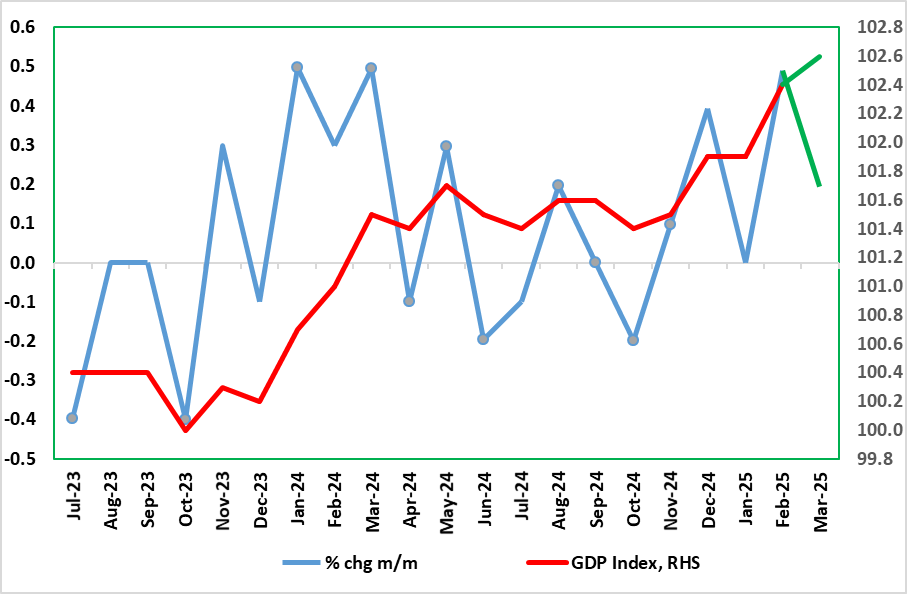

Figure: Actual GDP Looking Far Better into Early 2025 as in Early 2024

National account data delivered yet another upside surprise both in terms of the latest monthly figure and also the associated Q1 update. Indeed, February GDP, rather than consolidating in the March GDP release with a flat m/m reading, instead grew by 0.2%, a fifth successive non-negative outcome, led this time by services. Partly as a result, Q1 GDP rose by 0.7%, boosted both by exports and business investment. Notably, consumer spending rose a tame 0.2%, possibly a result of higher household inflation in the quarter, this worrying given the more marked rise seen this quarter in regard to price pressures. The data is unlikely to make any difference to BoE thinking which foresaw a 0.6% Q1 rise and one that still led to a marginal emergence of an output gap, this reflecting a (very justifiable) view that the official data are overstating actual activity which is more likely to have been near zero last quarter with a similar, if not weaker, picture envisaged for the current quarter, still leaving sub-1% overall GDP growth this year.

UK data can be erratic, but the hugely unexpected surge in February GDP numbers looked hard to fathom when the data surfaced and still seems puzzling. That unrevised 0.5% m/m jump suggested the economy grew by an annualized 6%-plus in the month. This is hard to square against the message from surveys and other data. More notable the February rise was based around a surge in manufacturing, also hard to assess given that this sector is where surveys suggest weakness is most paramount - there was a correction in March output. As for the March further rise, this was very much based around consumer services, very probably related to unseasonably warm weather, but not a degree that it propelled consumer spending much over Q1. Indeed, the latter laboured at 0.2%, possibly pressurized by a rise in the deflator, an ominous rise in the deflator (to 3.5%), a worrying feature given the more marked rise seen this quarter in regard to consumer price pressures – the BoE does not seem to regard that the emerging rise in inflation will take a toll on spending. Otherwise, the Q1 data was dominated by a rise in business investment and (net) exports, the former largely driven by aircraft imports which limited the latter although with export volumes pushed higher on the Non-EU side, presumably a reflection of bringing forward sales to the U.S. The data, does suggest a better productivity backdrop, especially on the basis of non official data which point to flat to falling employment.

But it is the outlook that will be dominating BoE thinking not least with tariffs coming in and where business worries were already fermenting given the weakness in surveys. And these surveys are used by the likes of the BoE to estimate underlying growth backdrop. On this basis, the BoE estimates that underlying growth in Q1 was around zero and where this lack of core momentum suggests that headline GDP growth will slow sharply in Q2, to 0.1%, with risks to the downside