This week's five highlights

Fiscal Elephant in the Room Ignored by BOE

RBA's Hawkish tilt

Norges Bank Ready For December Cut?

Riksbank Board Sticks to it Plans

Canada Budget Sees Larger Deficits, Slower Growth

Figure: BoE Presents Illustrative Paths for Bank Rate in the Central Projection and Alternative Scenarios

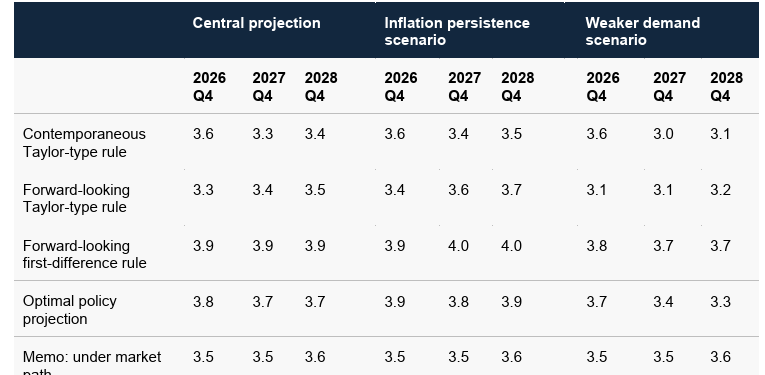

A tight vote was always likely for the November MPC verdict, but the 5:4 split was closer than expected, but almost a repeat of the August decision when rates were cut to the current 4%. What seems clear is that the effective swing voter was Governor Bailey but who coloured his decision with a clear pointer that he is likely to opt for a cut next month when more data will be available – an outlook we have had for some time. But this latest vote suggests that the two camps within the MPC may remain entrenched in their thinking for the time being, effectively meaning that Governor Bailey will remain the key, swing voter. In this regard, he seems willing to vote for up to three 25 bp cuts given his stressing that he sides with a policy outlook that sees Bank rate falling gradually further to around 3.3% by end-2026 (Figure). We largely adhere to this view but see the cuts coming sooner especially given the likely looming fiscal tightening which has yet to be factored into formal BoE thinking which still sees a virtual return of inflation to target.

Once again, the BoE presented three scenarios, with an inflation persistent view shaping the thinking of the MPC hawks while a downside risk alternative is what the dovish camp sided more with. In fact, they think that inflation risks have become more balanced as price persistence risks have diminished partly due to weaker demand both having occurred and expected. Notably, Governor Bailey seems to side with this scenario, he suggesting explicitly that the downside scenario seems more likely, this in his view possibly explaining elevated household savings and the Bank’s own survey intelligence on (elevated) uncertainty. But rather than cutting Bank Rate now, the Governor was explicit in suggesting he prefers to wait and see if the durability in disinflation is confirmed in upcoming economic developments this year but surely this also embodies a reaction to the likely sizeable fiscal tightening that the Nov 26 Budget is going to bring.

The RBA has kept the cash rate unchanged at 3.6% in the November 4th meeting as per forecast. With headline monthly inflation rising to the upper band of target range in Q3 and show little signs of moderation in October, the RBA thus revised their inflation forecast higher and see both trimmed mean and headline CPI to be above target range throughout most of 2026. They also only assume one more rate cut in 2026, which bring rates to around 3.35%.

The recent strength in headline CPI have driven RBA's forecast for CPI higher and seems to change their rate path with one less cut. Despite transitory factors are playing their part, the RBA seems to believe domestic demand and global factors will drive inflation higher, where we believe to be slightly drastic. Throughout the statement, we could see a lot of uncertainty between the lines where we could read as the continual of data dependency, just like previous statement. It warrants caution for dovish tilt in coming meetings.

Figure: CPI Dynamics On Target in Adjusted Short-Run Perspective

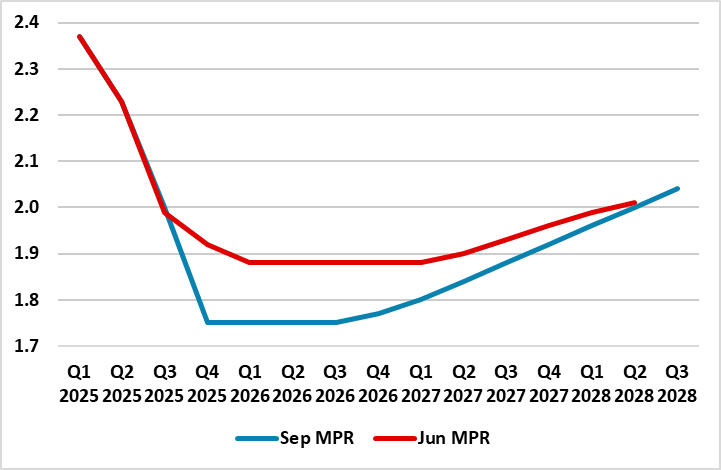

No change in policy and little shift in rhetoric was the message from the Norges Bank’s latest verdict. After what was to some a surprise (and seemingly far from a formality) move in September, in which the Norges Bank cut is policy rate by a further 25 bp to 4.0%, we see no change at Nov 6 verdict, there are no fresh forecasts, albeit with the Board still suggesting a further 25 bp move at the Dec 18 decision. That December meeting will have both new forecasts and data for the Board to peruse, not least inflation and lending numbers, the latter possibly becoming a worry given the fresh slowing in corporate credit growth. But with inflation dynamics ever more friendly, we still think that the Norges Bank is being too cautious and that (on the basis of its own calculations), policy will be very restrictive through the projected timeframe out to 2028 and where we wonder why official forecast see inflation only just approaching the 2% target by the end of that period even though it is already there when looked at through shorter-term dynamics (Figure).

We remain a little less confident about the extent of easing into 2026 but after another 25 bp cut likely in December we then envisage further such moves every quarter through next year. That would still leave the policy rate roughly in the middle of the neutral rate range estimated by the Norges Bank. In other words, the Norges Bank will be merely taking its foot of the brake, rather than pressing on the accelerator. But inflation worries continue to dominate Norges Bank thinking, although there were some slightly more reassuring cost insights from the Board in both acknowledging that unemployment has increased somewhat, and capacity utilisation in the economy has declined to a normal level – previously it has suggested less spare capacity than previously thought.

Figure: Riksbank Policy Rate Outlook

As we anticipated in our preview, the Riksbank Board is pleased with the data flow since its last and very probably final rate cut on Sep 23 (to 1.75%). GDP indicators suggest a strong Q3 showing of over 1% q/q while previously troublesome CPI data have softened appreciably thereby confirming (both our and Board) suspicions that the prior spike was aberrant. Admittedly, that GDP pick-up may be aberrant too, not least given the still gloomy message from the Riksbank’s own business survey and what are still soft labor market and monetary numbers. Thus the existing Board promise of no change was adhered to this time around, with the lack of any scheduled updated projections making the policy outlook beyond still uncertain. Regardless, we do not see any looming policy reversal, as we see this current policy rate (1.75%) staying in place through 2027, ie a little longer than the Riksbank (Figure).

Indeed, it now seems all the clearer that the CPI spike seen in the July data was aberrant even though it partly persisted into August – flash October data (Nov 6) may show a very decisive drop for targeted CPIF inflation to a 5-6 moth low of around 2.6%. Indeed, that spike was almost certainly a reflection of temporary factors, most notably energy price swings, alongside what may be a more sustained but far from demand-driven recent tripling in food inflation. To us, the underlying picture is reassuring as seen in the ex-energy CPIF measures is still consistent with target and this is despite the impact on this measure of food inflation, albeit where the latter has slowed from running at over 5% to just over 3% (still something more supply driven and also likely to weigh on spending power). Indeed, the Board view still suggests that ‘several indicators support the view that inflation will fall back to target going forward’. Notably the updated Riksbank CPIF forecast shows inflation well above target through 2028 but this is a result of VAT tax swing induced base effects that anything underlying.

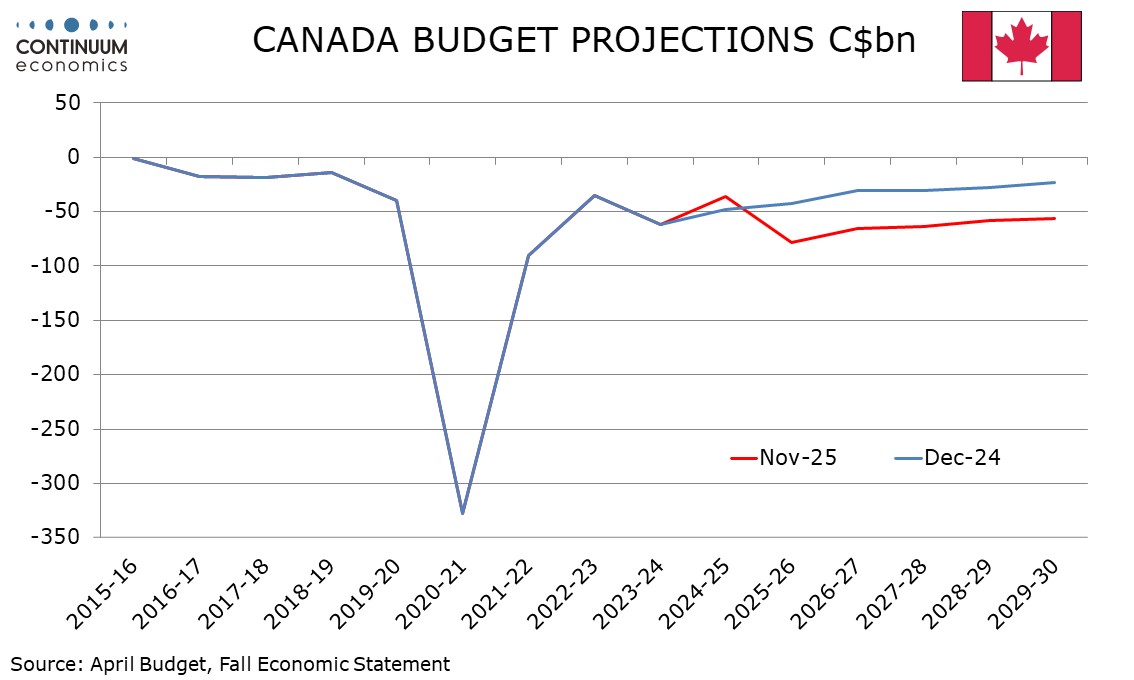

Canada’s budget has seen the deficit for 2025-26 revised up to C$78.3bn from C$42.2bn in the December 2024 statement, which will now be 2.5% of GDP versus 1.3%, still a level that is quite small compared to many other developed countries. The deficit is projected to slip after that, reaching C$56.6bn or 1.5% of GDP in 2029-30, though this is still twice as large as expected in December 2024.

The revisions to the deficit come in part from lower revenues as US tariffs hit near term Canadian growth, with GDP now seen rising by 1.2% in 2026 and 1.1% in 2025 versus previous forecasts of 2.1% and 1.9% respectively. This will mark a permanent downgrade of Canada’s potential, with GDP still seen rising by around 2.0% from 2027 through 2029, the downgrades to 2025 and 2026 not being offset by upgrades to latter years.

The increase in the 2025-26 deficit from the December forecast sees $7.1bn coming from in economic and fiscal developments, C$9.0bn coming from policy actions taken before this budget, and C$20.1bn from measures taken in this budget. Increased spending is seen in infrastructure, productivity and competitiveness, defense and housing, partially offset by savings in the civil service, tax collection and foreign aid.